Samira Saleh Al-Naimi

Over the past few years, a troubling new trend at the international human rights level is being observed, where discourses on ‘protecting the family’ are being employed to defend violations committed against family members, to bolster and justify impunity, and to restrict equal rights within and to family life.

The campaign to "Protect the Family" is driven by ultra-conservative efforts to impose "traditional" and patriarchal interpretations of the family, and to move rights out of the hands of family members and into the institution of ‘the family’.

Since 2014, a group of states have been operating as a bloc in human rights spaces under the name “Group of Friends of the Family”, and resolutions on “Protection of the Family” have been successfully passed every year since 2014.

This agenda has spread beyond the Human Rights Council. We have seen regressive language on “the family” being introduced at the Commission on the Status of Women, and attempts made to introduce it in negotiations on the Sustainable Development Goals.

AWID works with partners and allies to jointly resist “Protection of the Family” and other regressive agendas, and to uphold the universality of human rights.

In response to the increased influence of regressive actors in human rights spaces, AWID joined allies to form the Observatory on the Universality of Rights (OURs). OURs is a collaborative project that monitors, analyzes, and shares information on anti-rights initiatives like “Protection of the Family”.

Rights at Risk, the first OURs report, charts a map of the actors making up the global anti-rights lobby, identifies their key discourses and strategies, and the effect they are having on our human rights.

The report outlines “Protection of the Family” as an agenda that has fostered collaboration across a broad range of regressive actors at the UN. It describes it as: “a strategic framework that houses “multiple patriarchal and anti-rights positions, where the framework, in turn, aims to justify and institutionalize these positions.”

Данные будут обработаны в статистических целях, чтобы осветить состояние ресурсного обеспечения феминистских движений во всем мире, и представлены будут только в обобщенном виде. AWID не будет публиковать информацию о конкретных организациях или отображать информацию, которая позволила бы идентифицировать организации по их местоположению или характеристикам, без их согласия.

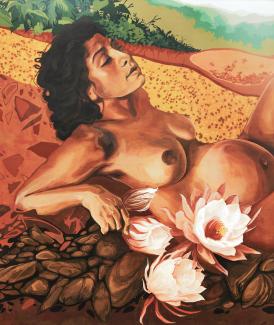

El Colectivo Moriviví es una colectiva de solo mujeres. Nuestra producción artística consiste en muralismo, muralismo comunitario y acciones/performances de protesta. Nuestro trabajo tiene como objetivo democratizar el arte y llevar a la esfera pública las narrativas de las comunidades de Puerto Rico, para generar espacios en donde sean validadas. Creemos que, a través del artivismo, podemos promover conciencia sobre temas sociales y fortalecer nuestra memoria colectiva.

En el marco de su participación en el Grupo de Trabajo Artístico de AWID, el Colectivo Moriviví convocó a un grupo diverso de afiliadxs, asociadxs y personal de AWID y facilitó un proceso colaborativo de imaginación, configuración y decisión sobre el contenido para la creación de un mural comunitario, a través de un proceso de creación conjunta en múltiples etapas. El proyecto comenzó con una conceptualización remota con feministas de diferentes zonas del planeta reunidxs por AWID, y luego evolucionó hacia su recontextualización y realización en Puerto Rico. Nos honra haber contado con la contribución de las artistas locales Las Nietas de Nonó (@lasnietasdenono), la participación de mujeres locales en la Sesión de Pintura Comunitaria, el apoyo logístico de la Municipalidad de Caguas, y el apoyo adicional al colectivo, brindado por FRIDA Young Feminist Fund.

El mural explora la trascendencia de las fronteras, al presentar cuerpos como un mapa en un abrazo que realza la intersección de las distintas manifestaciones, prácticas y realidades feministas.

Agradecemos también a Kelvin Rodríguez, quien documentó y captó las diferentes etapas de este proyecto en Puerto Rico:

Binta Sarr fue una activista por la justicia social, económica, cultural y política, y una ingeniera hidráulica en Senegal. Después de 13 años en la administración pública, Binta dejó ese camino para trabajar con mujeres rurales y marginadas.

Fue de este compromiso que surgió la Association for the Advancement of Senegalese Women [Asociación para el Avance de las Mujeres Senegalesas] (APROFES, por sus siglas en inglés), un movimiento y organización de base que Binta fundó en 1987. Uno de sus principales enfoques fue la formación de dirigentes, en relación no solo con las actividades económicas, sino también con los derechos de las mujeres y el acceso a los puestos de toma de decisiones.

"Las poblaciones de base deben organizarse, movilizarse, asumir el control ciudadano y exigir la gobernabilidad democrática en todos los sectores del espacio público. La prioridad de los movimientos sociales debe ir más allá de la lucha contra la pobreza y debe centrarse en programas de desarrollo articulados y coherentes en consonancia con los principios de los derechos humanos, teniendo en cuenta al mismo tiempo sus necesidades y preocupaciones tanto a nivel nacional como subregional y desde una perspectiva de integración africana y mundial". - Binta Sarr

Partiendo de la convicción de Binta de que el cambio fundamental de la condición de la mujer requiere una transformación de las actitudes masculinas, APROFES adoptó un enfoque interdisciplinario, al utilizar la radio, los seminarios y el teatro popular, además de proporcionar una educación pública innovadora y brindar apoyo cultural a las acciones de sensibilización. Su compañía de teatro popular representó piezas originales sobre el sistema de castas en el Senegal, el alcoholismo y la violencia conyugal. Binta y su equipo también analizaron la conexión crucial entre la comunidad y el mundo en general.

"Para APROFES, se trata de estudiar y tener en cuenta las interacciones entre lo micro y lo macro, lo local y lo global y también, las diferentes facetas del desarrollo. Desde la esclavitud hasta la colonización, el neocolonialismo y la mercantilización del desarrollo humano, la mayor parte de los recursos de África y del Tercer Mundo (petróleo, oro, minerales y otros recursos naturales) están todavía bajo el control de carteles financieros y las otras multinacionales que dominan este mundo globalizado". - Binta Sarr

Binta fue una de las integrantes fundadoras de la sección femenina de la Asociación Cultural y Deportiva Magg Daan. Recibió distinciones del Gobernador Regional y del Ministro de Hidrología por su "devoción por la población rural".

Nacida en 1954 en Guiguineo, un pequeño pueblo rural, Binta falleció en septiembre de 2019.

"La pérdida es inconmensurable, el dolor es pesado y profundo, pero resistiremos para no llorar a Binta; no lloraremos a Binta, mantendremos la imagen de su amplia sonrisa en todas las circunstancias, para resistir e inspirarnos en ella, para mantener, consolidar y desarrollar su obra..." - Página de Facebook de Aprofes, 24 de septiembre de 2019.

"¡Adiós Binta! Creemos que tu inmenso legado será preservado." - Elimane FALL , presidente de ACS Magg-Daan

by Prinka Saraswati

The menstrual cycle usually lasts between 27 and 30 days. During this time, the period itself would only go on for five to seven days. During the period, fatigue, mood swings, and cramps are the result of inflammation. (...)

< artwork: “Feminist Movement” by Karina Tungari

Não. Tem por base a história de 20 anos da AWID de mobilizar mais financiamento de maior qualidade para mudanças sociais lideradas por feministas e é a terceira edição do nosso inquérito “Onde está o dinheiro para organização feminista?”. O nosso objetivo é repetir o inquérito WITM a cada 3 anos.

Les antidroits ont adopté une double stratégie : outre leurs attaques ouvertes sur le système multilatéral, ils et elles sapent les droits humains depuis l’intérieur. Leur implication vise à prendre le contrôle des processus, instaurer des normes régressives et fragiliser la redevabilité.

Leur implication dans les sphères des droits humains a un but essentiel : saper le système et sa capacité à respecter, protéger et assurer les droits humains de tout un chacun, et à tenir les États membres pour responsables de leurs enfreintes. Certaines tactiques antidroits en dehors de l’ONU visent à la délégitimer, exercer des pressions politiques pour limiter son financement ou se retirer d’accords internationaux sur les droits humains. Les acteur·rice·s antidroits gagnent cependant en influence au sein même de l’ONU. Leurs tactiques de l’intérieur incluent la formation de délégué·e·s, la dénaturation de cadres relatifs aux droits humains, la dilution de la substance d’accords sur les droits humains, l’infiltration de comités d’ONG, la demande du statut ECOSOC sous un nom neutre, l’infiltration des espaces des jeunes et la pression pour que des acteur·rice·s antidroits occupent des postes clés.

Laurie Carlos était une comédienne, réalisatrice, danseuse, dramaturge et poétesse aux États-Unis. Artiste hors pair et visionnaire, c’est avec de puissants modes de communication qu’elle a su transmettre son art.

« Laurie entrait dans la pièce (n’importe quelle pièce/toutes les pièces) avec une perspicacité déroutante, un génie artistique, une rigueur incarnée, une féroce réalité – et une détermination à être libre... et à libérer les autres. Une faiseuse de magie. Une devineresse. Une métamorphe. Laurie m’a dit un jour qu’elle entrait dans le corps des gens pour trouver ce dont ils et elles avaient besoin. » - Sharon Bridgforth

Elle a employé plusieurs styles de performance alliant les gestes rythmiques au texte. Laurie encadrait les nouveaux·elles comédien·ne·s, performeur·euse·s et dramaturges, et a contribué à développer leur travail dans le cadre de la bourse Naked Stages pour les artistes émergent·e·s. Associée artistique au Penumbra Theatre, elle a participé à la sélection de scripts à produire, dans l’objectif « d’intégrer des voix plus féminines dans le théâtre ». Laurie faisait également partie des Urban Bush Women, une compagnie de danse contemporaine reconnue qui contait les histoires de femmes de la diaspora africaine.

Elle fit ses débuts à Broadway dans le rôle de Lady in Blue, en 1976, dans la production originale et primée du drame poétique For colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf de Ntozake Shange. L’oeuvre de Laurie inclut White Chocolate, The Cooking Show et Organdy Falsetto.

« Je raconte les histoires à travers le mouvement – les danses intérieures qui se produisent spontanément, comme dans la vie – la musique et le texte. Si j’écris une ligne, ce n’est pas forcément une ligne qui sera dite ; ce peut être une ligne qui sera bougée. Une ligne à partir de laquelle de la musique est créée. Le geste devient phrase. Tant de ce que nous sommes en tant que femmes, en tant qu’êtres, tient aux gestes que nous exprimons les un·e·s par rapport aux autres, tout le temps, et particulièrement dans les moments d’émotion. Le geste devient une phrase, ou un état de fait. Si j’écris “quatre gestes” dans un script, cela ne signifie pas que je ne dis rien;cela veut dire que j’ai ouvert la voie à ce que quelque chose soit dit physiquement. » Laurie Carlos

Laurie est née et a grandi à New York, a travaillé et vécu à Minneapolis-Saint-Paul. Elle est décédée le 29 décembre 2016, à l’âge de 67 ans, après un combat contre le cancer du côlon.

« Je pense que c’était exactement l’intention de Laurie. De nous sauver. De la médiocrité. De l’ego. De la paresse. De la création artistique inaboutie. De la paralysie par la peur.

Laurie voulait nous aider à briller pleinement.

Dans notre expression artistique.

Dans nos vies. » - Sharon Bridgforth pour le Pillsbury House Theatre

« Quiconque connaissait Laurie aurait dit que c’était une personne singulière. Elle était sa propre personne. Elle était sa propre personne, sa propre artiste ; elle mettait en scène le monde tel qu’elle le connaissait avec un vrai style et une compréhension fine, et elle habitait son art. » – Lou Bellamy, Fondatrice de la Penumbra Theatre Company, pour le Star Tribune

Lire un hommage complet par Sharon Bridgforth (seulement en anglais)

por Dr. Pragati Singh

En 2019, fui invitada por la BBC para hablar en la 100 Women Conference en Delhi, India. El tema era «El futuro del amor, las relaciones, y las familias». El público presente en el gran salón consistía mayoritariamente en jóvenes indixs: estudiantes universitarixs, profesionales, activistas, etc. (...)

arte: «Angels go out at night too» [Los ángeles también salen de noche], Chloé Luu >

إن كانت لديكم/ن أسئلة أو أمور تثير قلقكم/ن، الرجاء التوجه الينا عن طريق هذا النموذج وكتابة "استطلاع أين المال" في العنوان أو راسلنا على witm@awid.org

Al unirte a AWID, te sumas a un proceso organizativo feminista mundial, un poder colectivo surgido del trabajo entre movimientos y basado en la solidaridad.

Roxana Reyes Rivas, philosopher, feminist, lesbian, poet, politician and LGBT and women’s rights activist from Costa Rica. Owner of a sharp pen and incisive humour, a laugh a minute. She was born in 1960 and raised in San Ramón of Alajuela, when it was a rural town, and her whole life she would break away from the mandates of what it meant to be a woman.

With El Reguero (Costa Rican lesbian group) she organized lesbian festivals for over a decade, fun-filled formative spaces to come together at a time when the Costa Rican government and society persecuted and criminalized the lesbian existence. For hundreds of women the lesbian festivals where the only place they could be themselves and come together with others like them.

Roxana would often say founding political parties was one of her hobbies. “It’s important for people to understand there are other ways to do politics, that many issues need to be solved collectively”. She was one of the founders of the New Feminist League and VAMOS, a human rights focused political party.

“The philosophical trade is meant to jab, to help people ask themselves questions. A philosopher who doesn’t irritate anyone is not doing her job”. For 30 years Roxana taught philosophy at several Costa Rican public universities. Through her guidance, generations of students reflected about the ethical dilemmas in science and technology.

Roxana’s favourite tool was humour, she created the Glowing Pumpkin award, an acknowledgement to ignorance that she would bestow upon public figures, through her social media channels, mocking their anti-rights expressions and statements.

An aggressive cancer took Roxana at the end of 2019, before she could publish a compilation of her poems, a departing gift from the creative mind of a feminist who always raised her voice against injustice.

par Haddy Jatou Gassama

Il est de coutume pour la tribu mandingue, en Gambie, de mesurer la première écharpe utilisée par les mères pour porter leur nourrisson sur leur dos. (...)

illustration : « Puta sacrée », par Pia Love >

Are you job hunting? One of the perks of joining the AWID Community, is getting access to our community curated jobs board. You'll get to explore new opportunities, and you will also have the chance to share vacancies and call for proposals with all members.

|

Jurema Araújo est une enseignante-poète originaire de Rio de Janeiro. Elle a contribué au magazine Urbana, édité par les poètes Brasil Barreto et Samaral (paix à son âme) et au livre Amor e outras revoluções (L’amour et autres révolutions) avec plusieurs autres écrivain·e·s. En collaboration avec Angélica Ferrarez et Fabiana Pereira, elle a coédité O livro negro dos sentidos (Le livre noir des sens), une anthologie créative sur la sexualité des femmes noires au Brésil. Jurema a 54 ans ; elle a une fille, trois chiens, un chat et beaucoup d’ami·e·s. |

Tu la suces avec moi?La mangue est mon fruit préféré. |

Je vais être honnête : lorsque Angélica et Fabi m’ont proposé de créer une collection de textes érotiques écrits par des femmes noires, j’ignorais ce que c’était que de produire un recueil. Je maîtrisais le thème de l’érotisme, mais créer un recueil… J’ai souri, timide et flattée. Je crois que je les ai remerciées – du moins je l’espère! – et je me suis dit : mais qu’est-ce que c’est que ce truc, putain?! C’est quoi ce mot pompeux que je vais devoir intégrer tout en le mettant en pratique?

Aujourd’hui, je sais ce que c’est que de créer un recueil : c’est faire l’amour avec les écrits de quelqu’un d’autre, avec l’art de quelqu’un d’autre dans le but d’en faire un livre. Et c’est exactement ce que j’ai fait. J’ai dévêtu le texte de chaque autrice avec une lascivité littéraire. J’ai eu un rapport avec les mots et les sens d’autres personnes. J’ai été pénétrée par des poèmes que je n’avais pas écrits; des contes que je n’aurais jamais osé imaginer m’ont retournée, ont chamboulé mes sentiments, ma libido. Et c’était un orgasme inhabituel et merveilleux : éthéré, corporel, sublime, à la fois intellectuel et sensitif.

Ces textes pulsaient comme un clito durci par le désir, trempé, dégoulinant de joie à chaque lecture. Des mots dont la grivoiserie m’aspirait, me faisant plonger plus profondément dans cet univers humide.

Ces femmes noires sont allées au fond de leur excitation et ont transformé leurs fantasmes érotiques les plus profonds en art. Ces œuvres sont imprégnées de la manière dont chaque autrice vit la sexualité : libre, noire, individuelle, la sienne, son pouvoir retrouvé.

J’ai choisi de classer les textes en différentes parties dans le livre, chacune étant organisée en fonction du contenu le plus délicat, explosif, évident ou implicite qu’elle renfermait.

Pour ouvrir la porte à cette « envulvée noiressence », nous proposons la section Préliminaires, avec des textes qui introduisent le lecteur dans ce monde de délices. Il s’agit d’une caresse plus générale et délicate afin d’accueillir les sujets que les textes aborderont dans le reste du livre.

Puis vient la chaleur du Toucher, qui évoque les ressentis de la peau. Cette énergie qui brûle ou transite nos corps, fait bouillir nos hormones et éveille à leur tour nos autres sens. Et même si nous sommes nombreux·ses à être voyeurs·euses, le contact de la peau sur une bouche humide et chaude est excitant, comme si vous naviguiez dans la douceur de la personne qui se trouve avec vous. On est séduit par le contact ferme ou doux qui nous fait frissonner et ce picotement délicieux qui nous traverse du cou au bas du dos et qui ne disparaît que le lendemain. Et la chaleur des lèvres, la bouche, la langue humide sur la peau – ah! la langue dans l’oreille, mmmm – ou peau contre peau, les vêtements glissant sur les corps, comme s’ils se voulaient une extension de la main de l’autre. S’il n’y a pas d’urgence, l’excitation absolument sauvage d’une étreinte ferme, un peu de douleur – ou pourquoi pas, beaucoup?

La section Son – ou mélodie? – nous montre que l’attirance pour une personne passe également par l’ouïe : c’est la voix, les chuchotements, cette musique qui permet la connexion des corps et peut constituer la trame même du désir. Pour certain·e·s d’entre nous, la seule voix d’une personne ayant un joli timbre, qu’il soit rauque, traînant ou mélodieux, suffirait à nous donner un orgasme auditif. Elle n’aurait qu’à jurer grossièrement ou nous murmurer des mots doux à l’oreille pour nous faire frissonner du cou au coccyx.

Dans Saveur, nous confirmons que la langue est imbattable lorsqu’il s’agit d’aller goûter les endroits les plus enfouis et parcourir les corps pour se faire plaisir. Parfois, on l’utilise audacieusement pour goûter le nectar de l’autre. L’idée d’offrir sa fraise ou sa mangue délicieuse et juteuse à des morsures ou des coups de langue – ou des coups de langue et des morsures – nous désarme. Mais rien n’est plus délicieux que de goûter aux grottes et collines de la personne avec laquelle on est. Enfoncez votre langue bien profond pour goûter à ce bout de fruit… ou passez des heures à goûter le gland d’une queue dans votre bouche, passez votre langue sur des seins gourmands pour en goûter leurs tétons. Il s’agit de se souvenir d’une personne par la Saveur qu’elle nous a laissée.

Il y a aussi les textes où c’est le nez qui déclenche le désir. L’Odeur, mes chers·ères lecteurs·trices, est capable de nous éveiller aux délices du désir. Parfois, nous rencontrons des gens qui sentent si bon que nous voudrions les aspirer par le nez. Lorsque vous sillonnez le corps de l’autre avec le nez en commençant par le cou, sentez ce frisson délicieusement inconfortable qui parcourt votre colonne vertébrale et déshabille votre âme! Ce nez impudent se déplace ensuite vers la nuque où il capture le parfum de l’autre de telle sorte qu’en l’absence de cette personne, ce même parfum évoque, voire se répand en nous dans des souvenirs olfactifs qui ressuscitent l’odeur affolante de cette dernière.

Nous en venons au Regard – le plus traître des sens selon moi – où nous percevons le désir à partir d’un point de « vue ». Les textes présentent le désir et l’excitation par le biais de la vue, qui à son tour provoque les autres sens. Il suffit parfois d’un sourire pour nous rendre dingues. L’échange de regards? Celui qui dit : « J’ai envie de toi, là, maintenant ». Ce regard possédé qui s’éteint quand vous avez fini de baiser, ou pas. Celui-là est très particulier; il attire à lui l’autre qui ne pourra en détourner ses yeux très longtemps. Ou les regards du coin de l’œil – quand on détourne le regard au moment où l’autre va tourner la tête, comme un jeu du chat et de la souris? Pris·e·s en flagrant délit, il ne nous reste plus qu’à lui décocher un large sourire.

Pour finir, l’explosion. En se promenant à travers Tous les sens, les textes mêlent des sentiments qui prennent des allures d’alarme et nous entraînent vers le plaisir suprême : l’orgasme.

Bien sûr, ces différents contes et poèmes ne diffèrent d’aucune façon explicite. Certains sont subtils. L’excitation fait appel à tous nos sens et, plus fondamentalement, à notre tête. C’est là que ça se passe, c’est là que se fait la connexion à tout notre corps. J’ai organisé les poèmes selon la façon dont je les sentais à chaque lecture. Libre à vous de ne pas être d’accord! Mais pour moi, il existe un sens particulier par lequel le désir passe et puis explose. Et il y a quelque chose de délicieux à découvrir duquel il s’agit.

Pour pouvoir transformer l’excitation en art, nous devons nous libérer de tous nos préjugés, de nos prisons et des stigmates dans lesquels cette société centrée sur les Blancs nous a enfermé·e·s.

Chaque fois qu’une autrice noire transforme l’érotique en art, elle brise ces chaînes racistes et néfastes qui paralysent son corps, répriment sa sexualité et nous transforment en objet de convoitise d’un autre. Écrire de la poésie érotique, c’est reprendre le pouvoir sur son propre corps et parcourir sans crainte les délices du désir pour soi-même, pour les autres, pour la vie.

L’érotisme littéraire reflète ce que nous sommes lorsque nous en faisons de l’art. Nous montrons ici le meilleur de nous-mêmes, nos visions de l’amour trempées de plaisir, assaisonnées d’érogénéité, répandues dans nos corps et traduites par notre conscience artistique. Nous sommes multiples et nous partageons cette multiplicité de sensations dans des mots dégoulinants d’excitation. Oui, même nos mots dégoulinent de notre désir sexuel, mouillant nos vers, transformant nos pulsions sexuelles en paragraphes. Pour nous, jouir est révolutionnaire.

Nous devons noircir nos esprits, nos corps et notre sexualité, renouer avec notre plaisir et nous réapproprier nos orgasmes. Ce n’est qu’alors que nous serons libres. Tout ce processus est une révolution et il se fait dans la douleur. Mais il y a du bonheur à se découvrir très différent·e·s de ce que l’on attendait de nous.

Je sens que je suis à vous, je suis à nous. Goûtez, prenez plaisir, régalez-vous de ces mots merveilleux avec nous.

Ce texte est une adaptation des introductions de “O Livro Negro Dos Sentidos” [Le livre noir des sens], un recueil érotique de poèmes composés par 23 autrices noires.

Cette édition du journal, en partenariat avec Kohl : a Journal for Body and Gender Research (Kohl : une revue pour la recherche sur le corps et le genre) explorera les solutions, propositions et réalités féministes afin de transformer notre monde actuel, nos corps et nos sexualités.

نصدر النسخة هذه من المجلة بالشراكة مع «كحل: مجلة لأبحاث الجسد والجندر»، وسنستكشف عبرها الحلول والاقتراحات وأنواع الواقع النسوية لتغيير عالمنا الحالي وكذلك أجسادنا وجنسانياتنا.