Doris Viloria Palomares

El Consejo de Derechos Humanos (CDH) es el cuerpo intergubernamental del sistema de las Naciones Unidas responsable de la promoción y protección de todos los derechos humanos en todo el mundo. El HRC se reúne en sesión ordinaria tres veces al año, en marzo, junio y septiembre. La La Oficina del Alto Comisionado para los Derechos Humanos (ACNUDH) es la secretaría del Consejo de Derechos Humanos.

Debate y aprueba resoluciones sobre cuestiones mundiales de derechos humanos y el estado de los derechos humanos en determinados países

Examina las denuncias de víctimas de violaciones a los derechos humanos o las de organizaciones activistas, quienes interponen estas denuncias representando a lxs víctimas.

Nombra a expertos independientes que ejecutarán los «Procedimientos Especiales» revisando y presentado informes sobre las violaciones a los derechos humanos desde una perspectiva temática o en relación a un país específico

Participa en discusiones con expertos y gobiernos respecto a cuestiones de derechos humanos.

A través del Examen Periódico Universal, cada cuatro años y medio, se evalúan los expedientes de derechos humanos de todos los Estados Miembro de las Naciones Unidas

Se está llevarando a cabo en Ginebra, Suiza del 30 de junio al 17 de julio de 2020.

AWID trabaja con socios feministas, progresistas y de derechos humanos para compartir conocimientos clave, convocar diálogos y eventos de la sociedad civil, e influir en las negociaciones y los resultados de la sesión.

Pour rendre visible la diversité des formes de financement de l’organisation des mouvements féministes.

No, you don't have to be an AWID member to participate but AWID members receive a discounted registration fee as well as a number of other benefits.

For additional questions, please use our contact form, and select “14th AWID Forum" from the dropdown menu.

En vigueur à compter du 25 avril 2023.

Veuillez cliquer ici pour consulter la version précédente de notre politique de confidentialité.

La présente politique de confidentialité présente la manière dont l'Association pour les droits des femmes dans le développement et nos filiales et sociétés affiliées (« AWID », « nous » ou « notre ») traitent les données personnelles que nous recueillons via notre site Web, renvoyant à la présente politique de confidentialité (le « site »), ainsi que via les réseaux sociaux, nos activités de marketing, nos événements en direct et autres activités décrites dans la présente politique de confidentialité (le « Service »).

Index

Les données personnelles que nous recueillons

Comment nous utilisons vos données personnelles

Comment nous partageons vos données personnelles

Vos choix

Autres sites et services

Sécurité

Transferts internationaux de données

Personnes mineures

Modifications de la politique de confidentialité

Comment nous contacter

Avis aux utilisateurs·trices européen·ne·s

Les données que vous nous communiquez. Les données personnelles que vous êtes susceptibles de nous fournir par l'intermédiaire du Service ou d'une autre manière comprennent :

Données de communication basées sur nos échanges avec vous, y compris lorsque vous nous contactez par le biais du Service, des médias sociaux ou autrement.

Collecte automatique de données. Nous, nos fournisseurs de services et nos partenaires commerciaux pouvons enregistrer automatiquement certaines informations vous concernant, concernant votre ordinateur ou appareil mobile, et votre interaction au fil du temps avec le Service, nos communications et autres services en ligne, telles que :

Cookies et technologies apparentées. Une partie de la collecte automatique décrite ci-dessus est facilitée par les cookies, qui sont de petits fichiers texte que les sites Internet stockent sur les appareils des utilisateurs·trices et qui permettent aux serveurs Web d'enregistrer les activités de navigation Web des utilisateurs·trices et de se souvenir de leurs informations, de leurs préférences et de leur statut de connexion lorsqu'ils naviguent sur un site. Les cookies utilisés sur nos sites comprennent à la fois des « cookies de session » qui sont supprimés lorsqu'une session se termine, des « cookies persistants » qui restent plus longtemps, des cookies de « première partie » que nous plaçons et des cookies de « tierce partie » placés par nos partenaires commerciaux et nos fournisseurs de services de tiers.

Vos données personnelles pourront être utilisées aux fins suivantes ou selon les modalités décrites au moment de la collecte :

Prestation de services et exploitation commerciale. Nous sommes susceptibles d’utiliser vos données personnelles pour :

Recherche et développement. Nous sommes susceptibles d'utiliser vos données personnelles à des fins de recherche et de développement, notamment pour analyser et améliorer le Service. Dans le cadre de ces activités, nous pouvons créer des données agrégées, dépersonnalisées et/ou anonymisées à partir des données personnelles que nous recueillons. Nous transformons les données personnelles en données dépersonnalisées ou anonymes en supprimant les informations qui permettent de vous identifier personnellement. Nous pouvons utiliser ces données agrégées, dépersonnalisées ou autrement anonymisées et les partager avec des tiers à nos fins commerciales légales, y compris pour analyser et améliorer le Service et promouvoir nos activités.

Publicité. Nos fournisseurs de services et nous-mêmes pouvons recueillir et utiliser vos données personnelles pour vous envoyer des communications de marketing direct. Vous pouvez demander à ne plus recevoir de communications promotionnelles comme décrit dans la section Désengagement du marketing ci-dessous.

Conformité et protection. Nous sommes susceptibles d’utiliser vos données personnelles pour :

Avec votre consentement. Dans certains cas, nous pourrons vous demander expressément votre accord avant de collecter, utiliser ou partager vos données personnelles, notamment lorsque la loi l'exige.

Cookies et technologies apparentées. En plus des autres utilisations incluses dans cette section, nous sommes susceptibles d’utiliser les Cookies et technologies apparentées décrites ci-dessus aux fins suivantes :

Conservation. Nous conservons généralement les données personnelles pour atteindre les fins pour lesquelles nous les avons recueillies, y compris pour satisfaire à toute exigence légale, comptable ou de déclaration, pour établir ou défendre des réclamations légales, ou à des fins de prévention de la fraude. Pour déterminer la période de conservation appropriée des données personnelles, nous pouvons prendre en compte des facteurs tels que la quantité, la nature et la sensibilité des données personnelles, le risque potentiel de préjudice lié à l'utilisation ou à la divulgation non autorisée de vos données personnelles, les fins auxquelles nous traitons vos données personnelles et si nous pouvons atteindre ces fins par d'autres moyens, ainsi que les exigences légales applicables.

Une fois que nous n'avons plus besoin des informations personnelles que nous avons collectées à votre sujet, nous pouvons soit les supprimer, soit les rendre anonymes, soit les exclure de tout traitement ultérieur.

Nous sommes susceptibles de partager vos données personnelles avec les parties suivantes et comme décrit par ailleurs dans la présente politique de confidentialité ou au moment de la collecte :

Sociétés affiliées. Notre société mère, nos filiales et nos sociétés affiliées, à des fins compatibles avec la présente politique de confidentialité.

Fournisseurs de services. Les tiers qui fournissent des services en notre nom ou qui nous aident à exploiter le Service ou notre entreprise (tels que l'hébergement, la technologie de l'information, l'assistance à la clientèle, la livraison de courriels, le marketing, la recherche sur les consommateurs·trices et l'analyse de sites Internet).

Processeurs de paiement. Toute information de carte de paiement que vous utilisez pour effectuer un achat sur le Service est collectée et traitée directement par nos processeurs de paiement, tels que Stripe. Stripe se réserve le droit d'utiliser ces données de paiement conformément à sa politique de confidentialité, à l'adresse https://stripe.com/fr/privacy. Vous pouvez également demander à être facturé·e par votre fournisseur de communications mobiles, qui utilisera vos données de paiement conformément à sa propre politique de confidentialité.

Tiers désignés par vous. Nous nous réservons le droit de partager vos données personnelles avec des tiers dès lors que vous nous en avez donné l'instruction ou que vous nous avez donné votre accord pour le faire. Nous partagerons les informations personnelles requises pour que ces autres entreprises puissent fournir les services que vous aurez sollicités. De plus, vous pouvez choisir de traduire le contenu généré par les utilisateurs·trices à l'aide de Google Translate. Google se réserve le droit d’utiliser ce contenu conformément à sa politique de confidentialité, https://policies.google.com.

Conseillers·ères professionnel·le·s. Les conseillers·ères professionnel·le·s, tel·le·s que les avocat·e·s, les auditeurs·trices, les banquiers·ières et les compagnies d'assurance or asureur·e·s, lorsque cela est nécessaire dans le cadre des services professionnels qu'ils·elles nous fournissent.

Autorités et autres. Les forces de l'ordre, les autorités gouvernementales et les parties privées, si nous estimons de bonne foi que cela est nécessaire ou approprié aux fins de conformité et de protection décrites ci-dessus.

Autres utilisateurs·trices. Votre profil et les autres données de contenu généré par les utilisateurs·trices (à l'exception des messages) sont potentiellement visibles par d'autres utilisateurs·trices du Service. Par exemple, d'autres utilisateurs·trices du Service peuvent avoir accès à vos informations si vous avez choisi de mettre votre profil ou d'autres données personnelles à leur disposition par le biais du Service, par exemple lorsque vous publiez des commentaires, des critiques, des réponses à des sondages ou que vous partagez d'autres contenus. Ces informations peuvent être vues, collectées et utilisées par d'autres, y compris être mises en cache, copiées, capturées à l'écran ou stockées ailleurs par d'autres (par exemple, les moteurs de recherche), et nous ne prenons pas la responsabilité d'une telle utilisation de ces informations.

Dans cette section, nous décrivons les droits et les choix disponibles pour tous les utilisateurs·trices. Les utilisateurs·trices qui se trouvent au Royaume-Uni, en Suisse et dans l’Espace économique européen peuvent trouver des informations supplémentaires sur leurs droits ci-dessous.

Refus des communications publicitaires. Vous pouvez renoncer à recevoir des courriels à caractère commercial en suivant les instructions d’opposition ou de désabonnement figurant au bas du courriel, ou en nous contactant. Notez que si vous choisissez de vous désabonner des courriels à caractère publicitaire, vous continuerez peut-être à recevoir des courriels liés au Service et d'autres courriels à caractère non publicitaire.

Refuser de fournir des informations. Il nous est nécessaire de collecter des données personnelles pour fournir certains services. Si vous ne fournissez pas les informations que nous jugeons requises ou obligatoires, nous pourrions ne pas être en mesure de fournir ces services.

Supprimer votre contenu ou mettre fin à votre adhésion. Vous pouvez choisir de supprimer certains contenus que vous nous avez fournis. Si vous souhaitez faire la demande de mettre fin à votre adhésion, veuillez nous contacter.

Le Service est susceptible de contenir des liens vers des sites Internet, des applications mobiles et d'autres services en ligne exploités par des tiers. En outre, il peut arriver que notre contenu soit intégré à des pages Internet ou à d'autres services en ligne qui ne nous sont pas associés. Ces liens et intégrations ne constituent pas une approbation de notre part, ni ne signifient que nous sommes affiliés à une tierce partie. Nous ne contrôlons pas les sites Internet, les applications mobiles ou les services en ligne exploités par des tiers, et nous ne sommes pas responsables de leurs actions. Nous vous encourageons à lire les politiques de confidentialité des autres sites Internet, applications mobiles et services en ligne que vous utilisez.

Nous employons un certain nombre de mesures de protection techniques, organisationnelles et physiques conçues pour protéger les données personnelles que nous recueillons. Cependant, le risque de sécurité est inhérent à toutes les technologies de l'Internet et de l'information et nous ne pouvons pas garantir la sécurité de vos données personnelles.

Notre siège social se trouve aux États-Unis mais nous nous réservons le droit de faire appel à des fournisseurs de services exerçant leurs activités dans d'autres pays. Vos données personnelles sont susceptibles d'être transférées aux États-Unis ou à d'autres endroits où les lois sur la protection de la vie privée pourraient ne pas être aussi protectrices que celles en vigueur dans votre État, votre province ou votre pays.

Il est recommandé aux utilisateurs·trices du Royaume-Uni, de la Suisse et de l'Espace économique européen de lire les informations importantes fournies ci-dessous concernant le transfert de données personnelles effectué en dehors de l'Union européenne.

Le Service n'est pas destiné à être utilisé par des personnes âgées de moins de 18 ans. Si vous êtes le parent ou un·e tuteur·trice d'un enfant auprès duquel vous pensez que nous avons recueilli des données personnelles de manière illégale, veuillez nous contacter. Si nous apprenons que nous avons recueilli des données personnelles par le biais du Service auprès d'une personne mineure sans le consentement de son parent ou de tuteur·trice tel que l'exige la loi, nous nous conformerons aux exigences légales applicables pour supprimer ces informations.

Nous nous réservons le droit de modifier cette politique de confidentialité à tout moment. Si nous y apportons des modifications importantes, nous vous en informerons en mettant à jour la date de cette politique de confidentialité et en l'affichant sur le Service ou par d'autres moyens appropriés. Toute modification de la présente politique de confidentialité entrera en vigueur dès que nous aurons publié la version modifiée (ou comme indiqué autrement au moment de la publication). Dans tous les cas, l'utilisation du Service après la date d'entrée en vigueur de toute politique de confidentialité modifiée indique que vous reconnaissez que la politique de confidentialité modifiée s'applique à vos interactions avec le Service et notre entreprise.

Avis aux utilisateurs·trices européen·ne·s

Domaines d’application du présent avis aux utilisateurs·trices européen·ne·s. Les informations fournies dans cette section « Avis aux utilisateurs·trices européen·ne·s » ne s'appliquent qu'aux personnes situées dans l'EEE ou au Royaume-Uni (les juridictions de l'EEE et du Royaume-Uni sont ensemble désignées par le terme « Europe »).

Données personnelles. Les références aux « données personnelles » dans la présente politique de confidentialité doivent être comprises comme incluant une référence aux « données personnelles » (telles que définies dans le RGPD) - c'est-à-dire les informations sur les individus à partir desquelles ils sont soit directement identifiés, soit identifiables. Elles n'incluent pas les « données anonymes » (c'est-à-dire les informations se rapportant à l'identité d’un individu ayant été définitivement supprimée). Les données personnelles que nous recueillons auprès de vous sont identifiées et décrites plus en détail dans la section « Informations personnelles que nous recueillons ».

Responsable du traitement. L’AWID est responsable du traitement de vos données personnelles couvertes par la présente politique de confidentialité aux fins de la législation européenne sur la protection des données (c'est-à-dire le RGPD de l'UE et le dénommé « RGPD du Royaume-Uni » (le « RGPD », le cas échéant)). Voir la section Comment nous contacter ci-dessus pour obtenir nos coordonnées.

Nos bases légales en matière de traitement de l'information. Le RGPD exige que nous nous assurions de disposer d'une « base légale » permettant l’utilisation de vos données personnelles pour toute raison que ce soit.

Nos bases légales pour le traitement de vos données personnelles décrites dans la présente politique de confidentialité sont énumérées ci-dessous.

Nous avons présenté ci-dessous, sous forme de tableau, les bases légales sur lesquelles nous nous appuyons en ce qui concerne lesdites Finalités justifiant l'utilisation de vos données personnelles - pour plus d'informations sur ces Finalités et les types de données concernés, voir Comment nous utilisons vos données personnelles ci-dessus.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conservation. Nous conservons les données personnelles aussi longtemps que nécessaire pour atteindre l’objectif pour lequel nous les avons recueillies, y compris pour satisfaire à toute exigence légale, comptable ou de déclaration, pour établir ou défendre des réclamations légales, ou à des fins de conformité et de protection, à moins qu'il ne soit spécifiquement autorisé de les conserver plus longtemps.

Pour déterminer la période de conservation appropriée des données personnelles, nous tenons compte de la quantité, de la nature et de la sensibilité des données personnelles, du risque potentiel de préjudice lié à l'utilisation ou à la divulgation non autorisée de vos données personnelles, des fins auxquelles nous traitons vos données personnelles et de la possibilité d'atteindre ces objectifs par d'autres moyens, ainsi que des exigences légales applicables.

Une fois que nous n'aurons plus besoin des données personnelles que nous avons recueillies à votre sujet, nous les supprimerons ou les rendrons anonymes ou, si cela n'est pas possible (par exemple, parce que vos données personnelles ont été stockées dans des archives de sauvegarde), nous conserverons vos données personnelles en toute sécurité et les exclurons de tout traitement ultérieur jusqu'à ce qu'il soit possible de les effacer. Dans le cas où nous rendons anonymes vos données personnelles (afin qu'elles ne puissent plus vous être associées), nous sommes en droit d'utiliser ces informations indéfiniment sans vous en informer davantage.

Informations complémentaires

Pas d’obligation de fournir des données personnelles. Vous n'êtes pas obligé·e de nous fournir des données personnelles. Cependant, dans le cas où nous devrions traiter vos données personnelles soit pour nous conformer à la loi applicable, soit pour vous fournir nos Services, et que vous ne nous communiqueriez pas ces données personnelles lorsque nous vous le demandons, nous pourrions ne pas être en mesure de vous fournir une partie ou la totalité de nos Services. Nous vous en informerons, si c'est le cas à ce moment-là.

Pas de prise de décision automatisée ni de profilage. Dans le cadre des Services, nous n'effectuons pas de prise de décision automatisée ni/ou de profilage entraînant des effets juridiques ou des effets significatifs similaires. Nous ne manquerons pas de vous faire savoir si la mise à jour de la présente politique de confidentialité entraîne quelque changement que ce soit.

Sécurité. Nous avons mis en place des procédures conçues pour faire face aux violations de données personnelles. Dans le cas de telles violations, nous avons adopté des procédures qui nous permettent de travailler avec les organismes de réglementation applicables. En outre, dans certaines circonstances (y compris lorsque nous sommes légalement tenu·e·s de le faire), nous pouvons vous avertir des violations affectant vos données personnelles.

Vos droits

Généralités. Les lois européennes sur la protection des données garantissent certains droits concernant vos données personnelles. Si vous résidez en Europe, vous pouvez nous demander de prendre l'une des mesures suivantes en ce qui concerne les données personnelles que nous détenons :

Comment faire valoir ses droits. Vous pouvez soumettre ces demandes par courrier électronique. Voir la section Comment nous contacter ci-dessus pour nos coordonnées. Nous sommes susceptibles de vous demander des informations spécifiques pour nous aider à confirmer votre identité et à traiter votre demande. Le fait que nous soyons tenu·e·s ou non de répondre à votre demande dépendra d'un certain nombre de facteurs (par exemple, pourquoi et comment nous traitons vos données personnelles), si nous rejetons une demande que vous pourriez faire (que ce soit en totalité ou en partie), nous vous communiquerons alors les raisons de cette décision, sous réserve de toute restriction légale. En règle générale, vous n'aurez pas de frais à payer pour exercer vos droits; cependant, nous pouvons exiger des frais raisonnables si votre demande est manifestement infondée, répétitive ou excessive. Nous essayons de répondre à toutes les demandes légitimes dans un délai d'un mois. Cela peut nous prendre plus d'un mois si votre requête est particulièrement complexe ou si vous en avez déposé plusieurs; dans ce cas, nous vous en informerons et vous tiendrons au courant.

Le droit de déposer une plainte auprès de votre autorité de surveillance. Outre les droits qui vous sont conférés ci-dessus, vous pouvez, si notre réponse à une demande que vous nous avez adressée ou la façon dont nous traitons vos données personnelles ne vous satisfont pas, déposer une plainte auprès de l'autorité de contrôle de la protection des données de votre lieu de résidence habituel.

The Information Commissioner’s Office

Water Lane, Wycliffe House

Wilmslow - Cheshire SK9 5AF

Tel. +44 303 123 1113

Site Internet : https://ico.org.uk/make-a-complaint/

Traitement des données en dehors de l'Europe; nous sommes une société basée aux États-Unis et nombre de nos prestataires de services, conseillers·ères, partenaires ou autres destinataires de données sont également basé·e·s aux États-Unis. Cela veut dire que vos données personnelles seront nécessairement consultées et traitées aux États-Unis si vous utilisez les Services. Elles peuvent également être fournies à des destinataires dans d'autres pays en dehors de l'Europe.

Pour rappel, les États-Unis ne font pas l'objet d'une « décision d'adéquation » au titre du RGPD - ce qui signifie, en substance, que le régime juridique américain n'est pas considéré par les organismes européens compétents comme offrant un niveau de protection des données personnelles adéquat et équivalent à celui fourni par les lois européennes en vigueur.

Lorsque nous partageons vos données personnelles avec des tiers qui sont basés en dehors de l'Europe, nous nous efforçons de garantir un degré de protection similaire conformément aux lois applicables en matière de protection de la vie privée en nous assurant que l'un des mécanismes suivants est bien mis en œuvre :

Pour plus d'informations concernant le mécanisme spécifique utilisé lors du transfert de vos données personnelles en dehors de l'Europe, n'hésitez pas à nous contacter.

AWID agradece a las numerosas personas cuyos análisis, ideas y contribuciones han dado forma a la investigación y las acciones de promoción de "¿Dónde está el dinero para las organizaciones feministas?" a lo largo de los años.

Ante todo, vaya nuestro agradecimiento más profundo a lxs afiliadxs y activistas de AWID que participaron en las consultas de ¿Dónde está el dinero? y ensayaron esta encuesta con nosotrxs, y que compartieron su tiempo, sus análisis y el corazón con tanta generosidad.

Expresamos nuestra gratitud a los movimientos, aliados y fondos feministas, entre otros, a Black Feminist Fund, Pacific Feminist Fund, ASTRAEA Lesbian Foundation for Justice, FRIDA Young Feminist Fund, Purposeful, Kosovo Women’s Network, Human Rights Funders Network, Dalan Fund y PROSPERA por su rigurosa investigación sobre el estado de la dotación de recursos, sus agudos análisis y promoción sostenida para más y mejor financiamiento y poder para las organizaciones feministas y por la justicia de género en todos los contextos.

We see Taipei as the location in the Asia Pacific region that will best allow us to build that safe and rebelious space for our global feminist community.

Taipei offers a moderate degree of stability and safety for the diversity of Forum participants we will convene. It also has strong logistical capacities, and is accessible for many travellers (with a facilitated e-visa process for international conferences).

The local feminist movement is welcoming of the Forum and keen to engage with feminists from across the globe.

.

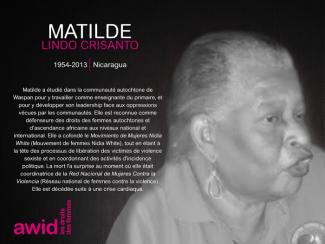

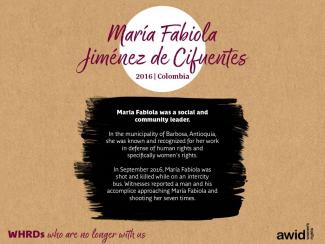

This year we are honoring 19 Women Human Rights Defenders from the Latin America and the Caribbean region. 16 defenders were murdered, including 6 journalists and 4 LGBTQI rights defenders. Please join us in commemorating the life and work of these women by sharing the memes below with your colleagues, friends and networks and by tweeting using the hashtags #WHRDTribute and #16Days.

Please click on each image below to see a larger version and download as a file

Écoutez cette histoire :

Absolutamente; deseamos saber de ustedes y su experiencia con la obtención de recursos.