Uma Singh

Women human rights defenders (WHRDs) worldwide defend their lands, livelihoods and communities from extractive industries and corporate power. They stand against powerful economic and political interests driving land theft, displacement of communities, loss of livelihoods, and environmental degradation.

Extractivism is an economic and political model of development that commodifies nature and prioritizes profit over human rights and the environment. Rooted in colonial history, it reinforces social and economic inequalities locally and globally. Often, Black, rural and Indigenous women are the most affected by extractivism, and are largely excluded from decision-making. Defying these patriarchal and neo-colonial forces, women rise in defense of rights, lands, people and nature.

WHRDs confronting extractive industries experience a range of risks, threats and violations, including criminalization, stigmatization, violence and intimidation. Their stories reveal a strong aspect of gendered and sexualized violence. Perpetrators include state and local authorities, corporations, police, military, paramilitary and private security forces, and at times their own communities.

AWID and the Women Human Rights Defenders International Coalition (WHRD-IC) are pleased to announce “Women Human Rights Defenders Confronting Extractivism and Corporate Power”; a cross-regional research project documenting the lived experiences of WHRDs from Asia, Africa and Latin America.

"Women Human Rights Defenders confronting extractive industries: an overview of critical risks and Human Rights obligations" is a policy report with a gender perspective. It analyses forms of violations and types of perpetrators, quotes relevant human rights obligations and includes policy recommendations to states, corporations, civil society and donors.

"Weaving resistance through action: Strategies of Women Human Rights Defenders confronting extractive industries" is a practical guide outlining creative and deliberate forms of action, successful tactics and inspiring stories of resistance.

The video “Defending people and planet: Women confronting extractive industries” puts courageous WHRDs from Africa, Asia, and Latin America in the spotlight. They share their struggles for land and life, and speak to the risks and challenges they face in their activism.

Challenging corporate power: Struggles for women’s rights, economic and gender justice is a research paper outlining the impacts of corporate power and offering insights into strategies of resistance.

AWID acknowledges with gratitude the invaluable input of every Woman Human Rights Defender who participated in this project. This project was made possible thanks to your willingness to generously and openly share your experiences and learnings. Your courage, creativity and resilience is an inspiration for us all. Thank you!

Sauf si vous avez des problèmes d’accessibilité et/ou que vous répondez aux questions de l’enquête dans une autre langue, nous vous encourageons fortement à utiliser KOBO pour une collecte et une analyse standardisées des données WITM.

After assessing your organization’s capacity and research goals, you may choose to conduct a survey as one of the methods of data collection for your research analysis.

In this section:

- Why conduct a survey?

- Identify your survey population 1. Online survey 2. Paper survey

- Create your questions 1. Short and clear questions 2. Simple and universal language 3. "Closed" and "open" questions 4. Logical organization 5. Less than 20 mins 6. Simple and exciting

- Test and translate 1. Your advisors 2. Draft and test 3. Translation

- Target the right population 1. Sample size 2. Degree of participation 3. Database and contact list

A survey is an excellent way to gather information on individual organizations to capture trends at a collective level.

For example, one organization’s budget size does not tell you much about a trend in women’s rights funding, but if you know the budgets of 1,000 women’s rights organizations or even 100, you can start to form a picture of the collective state of women’s rights funding.

As you develop your survey questions, keep in mind the research framing that you developed in the previous section.

Remember: Your framing helps you determine what information you are trying to procure through your survey. The data collected from this survey should allow you to accomplish your goals, answer your key questions, and create your final products.

This is an important step – the clearer you are about which populations you want to survey, the more refined your questions will be.

Depending on your research goals, you may want to create separate surveys for women’s rights organizations, women’s funds and donors. Or you may want to focus your survey on women’s groups and collect interviews for women’s funds and donors, as a survey for each population can be resource-intensive.

The questions you ask women’s groups may be different than ones you would ask women’s funds. If you plan on surveying more than one population, we encourage you to tailor your data collection to each population.

At the same time, some key questions for each population can and should overlap in order to draw comparative analysis from the answers.

If you can reach your survey population online, it is useful and efficient to create an online survey.

We recommend two online tools, both which offer free versions:

Survey Gizmo allows you to convert your data for SPSS, a statistical software useful for advanced data analysis

Your data analyst person(s) will be the best person(s) to determine which tool is best for your survey based on staff capacity and analysis plans.

For accessibility, consider making a PDF form version of your survey that you can attach via email. This ensures organizations that have sporadic internet connections or those that pay for it by the minute can download the survey and complete it without requiring a constant online connection.

You may decide that an online approach is not sufficiently accessible or inclusive enough for your popuation.

In this case, you will need to create a paper survey and methods to reach offline populations (through popular events or through post, with pre-stamped envelopes for returning).

Make it easy for participants to complete your survey.

If the questions are confusing or require complex answers, you risk having participants leave the survey unfinished or providing answers that are unusable for your analysis.

Ensure your questions only ask for one item of information at a time.

For example:

- What is your organization’s budget this year?

Easy to answer: participant can easily locate this information for their organization, and it is only asking for one item of information.- What percentage of your budget have you identified as likely sources for funding for your organization, but are still unconfirmed?

Confusing and difficult to answer: are you asking for a list of unconfirmed funding sources or percentage of funding that is likely but unconfirmed?

This information is difficult to obtain: the respondent will have to calculate percentages, which they may not have on hand. This increases the risk that they will not complete the survey.

Many words and acronyms that are familiar to you may be unknown to survey participants, such as “resource mobilization”, “WHRD”, and “M&E”, so be sure to choose more universal language to express your questions.

If you must use industry lingo – phrases and words common to your colleagues but not widely known – then providing a definition will make your survey questions easier to understand.

Be sure to spell out any acronyms you use. For example, if you use WHRD, spell it out as “Women’s Human Rights Defenders".

Closed questions:

Only one response is possible (such as “yes,” “no” or a number). Survey participants cannot answer in their own words and they typically have to choose from predetermined categories that you created or enter in a specific number. Responses to closed questions are easier to measure collectively and are often quantitative.

Example of a closed question: What is your organization’s budget?

Open-ended questions:

These are qualitative questions that are often descriptive. Respondents answer these questions entirely in their own words. These are more suitable for interviews than surveys.

They are harder to analyze at a collective level as compared to closed-end questions, especially if your survey sample is large. However, by making open-ended questions very specific, you will make it easier to analyze the responses.

Whenever possible, design your survey questions so that participants must select from a list of options instead of offering open-ended questions. This will save a lot of data cleaning and analysis time.

Example of open-ended question: What specific challenges did you face in fundraising this year?

Familiarize yourself with different types of questions

There are several ways to ask closed-ended questions. Here are some examples you can review and determine what fits best for the type of data you want to collect:

If you plan to conduct this research at regular intervals (such as every two years), we recommend developing a baseline survey that you can repeat in order to track trends over time.

Set 1: Screening questions

Screening questions will determine the participant’s eligibility for the survey.

The online survey options we provided allow you to end the survey if respondents do not meet your eligibility criteria. Instead of completing the survey, they will be directed to a page that thanks them for their interest but explains that this survey is intended for a different type of respondent.

For example, you only want women’s rights groups in a given location to take this survey. The screening questions can determine the location of the participant and prevent respondents from other locations from continuing the survey.

Set 2: Standardized, basic demographic questions

These questions would collect data specific to the respondent, such as name and location of organization. These may overlap with your screening questions.

If resources permit, you can store these answers on a database and only ask these questions the first year an organization participates in your survey.

This way when the survey is repeated in future years, it is faster for organizations to complete the entire survey, increasing chances of completion.

Set 3: Standardized and mandatory funding questions

These questions will allow you to track income and funding sustainability. Conducted every year or every other year, this allows you to capture trends across time.

Set 4: Special issues questions

These questions account for current context. They can refer to a changing political or economic climate. They can be non-mandatory funding questions, such as attitudes towards fundraising.

For example, AWID’s 2011 WITM Global Survey asked questions on the new “women & girls” investment trend from the private sector.

The shorter, the better: your survey shouldn’t exceed 20 minutes to ensure completion and respect respondents’ time.

It is natural to get excited and carried away by all the types of questions that could be asked and all the information that could be obtained. However, long surveys will lead to fatigue and abandonment from participants or loss of connection between participants and your organization.

Every additional question in your survey will add to your analytical burden once the survey is complete.

General tips

- Ask for exact budgets instead of offering a range (in our experience, specific amounts are more useful in analysis).

- Specify currency! If necessary, ask everyone to convert their answers to the same currency or ask survey takers to clearly state the currency they are using in their financial answers.

- Ensure you collect enough demographic information on each organization to contextualize results and draw out nuanced trends.

For example, if you are analyzing WITM for a particular country, it will be useful to know what region each organization is from or at what level (rural, urban, national, local) they work in order to capture important trends such as the availability of greater funding for urban groups or specific issues.

Involving your partners from the start will allow you to build deeper relationships and ensure more inclusive, higher quality research.

They will provide feedback on your draft survey, pilot test the survey, and review your draft research analysis drawn from your survey results and other data collection.

These advisors will also publicize the survey to their audiences once it is ready for release. If you plan on having the survey in multiple languages, ensure you have partners who use those languages.

If you decide to do both survey and interviews for your data collection, your advisor-partners on your survey design can also double as interviewees for your interview data collection process.

After your survey draft is complete, test it with your partners before opening it up to your respondents. This will allow you to catch and adjust any technical glitches or confusing questions in the survey.

It will also give you a realistic idea of the time it takes to take the survey.

Once the survey is finalized and tested in your native language, it can be translated.

Be sure to test the translated versions of your survey as well. At least some of your pilot testers should be native speakers of the translated languages to ensure clarity.

Your survey sample size is the number of participants that complete your survey.

Your survey sample should reflect the qualities of the larger population you intend to analyze.

For example: you would like to analyze the millions of women’s rights groups in Valyria but you lack the time and resources to survey every single one.

Instead, you can survey only 500 of the Valyrian women’s rights groups – a sample size - to represent the qualities of all the women’s groups in the region.

Recommended sample size

Although it is not necessary to determine your exact sample size before you launch your survey, having a size in mind will allow you to determine when you have reached enough participants or whether you should extend the dates that the survey is available, in case you feel that you have not reached enough people.

Even more important than size of a sample is the degree to which all members of the target population are able to participate in a survey.

If large or important segments of the population are systematically excluded (whether due to language, accessibility, timing, database problems, internet access or another factor) it becomes impossible to accurately assess the statistical reliability of the survey data.

In our example: you need to ensure all women’s groups in Valyria had the opportunity to participate in the survey.

If a segment of women’s groups in Valyria do not use internet, and you only pull participants for your sample through online methods, then you are missing an important segment when you have your final sample, thus it is not representative of all women’s groups in Valyria.

You cannot accurately draw conclusions on your data if segments of the population are missing in your sample size; and ensuring a representative sample allows you to avoid this mistake.

To gain an idea of what the makeup of women’s groups for your area of research (region, population, issue, etc) looks like, it may be useful to look at databases.

By understanding the overall makeup of women’s groups that you plan to target, you can have an idea of what you want your sample to look like - it should be like a mini-version of the larger population.

After participants have taken your survey, you can then gauge if the resulting population you reached (your sample size) matches the makeup of the larger population. If it doesn’t match, you may then decide to do outreach to segments you believe are missing or extend the window period that your survey is open.

Do not be paralyzed if you are unsure of how representative your sample size is – do your best to spread your survey as far and wide as possible.

4. Collect and analyze your data

Representó al Consorcio Internacional sobre Discapacidad y Desarrollo (IDDC por su sigla en inglés) durante la negociación de la Convención sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad (2001-2006). Su trabajo estaba dedicado a la implementación del objetivo de la Convención: el goce pleno de los derechos humanos universales por, para y con las personas con discapacidades, en pos de un mundo inclusivo, accesible y sostenible.

En sus propias palabras, su liderazgo consistía en «servir a la comunidad de personas con discapacidad, comenzando por aquellas pequeñas tareas que otrxs pueden no querer realizar».

Falleció el 27 de octubre de 2017 en su ciudad natal de Rosario, Argentina.

En esta nota puede leerse más sobre María Verónica Reina, en sus propias palabras.

Listen to the story here:

Yes, we invite you to share more on issues that are important to you by responding to the open question(s) at the end of the survey.

Ya tienes el producto final y completo de la investigación organizado y editado. Ahora querrás facilitar la difusión de los resultados y para ello necesitarás que sean visualmente accesibles e interesantes.

En esta sección

- Prepara el informe extenso para la difusión pública

1. Piensa tal como lo hace tu público

2. Trabaja con profesionales del diseño

3. Asegura la consistencia de los productos- Controla la calidad de las traducciones

Considera la posibilidad de elaborar productos más breves además del informe extenso.

Como dijéramos en «Sintetiza los resultados de la investigación», AWID muchas veces prepara productos más breves a partir del informe de investigación completo. Esto permite difundirlo más y mejor entre audiencias específicas de importancia clave.

Siempre ten presente cuál es la población a la que te diriges: ¿quién va a leer tu informe?

Ejemplos de productos breves derivados de un informe más extenso:

Todo el tiempo nos bombardean con información. Para conservar el interés de la audiencia, el producto deberá tener un atractivo visual. Una vez más, saber qué quieres lograr y a quién esperas llegar, permitirá que quien se encargue del diseño pueda crear productos para audiencias específicas.

Un informe escrito de muchas páginas en PDF tal vez te parezca la única forma posible de presentar la investigación, pero a mucha gente le puede resultar abrumador — sobre todo en Internet.

Si quieres compartir el producto con una comunidad en línea, piensa en crear memes e infografías para usar en las redes sociales, blogs y plataformas virtuales.

Para decidir si vas a crear o no productos más breves, piensa si podrás dividir los resultados en varios productos más breves para compartirlos con poblaciones específicas o en distintos momentos del año, reavivando así el interés por el producto.

Si cuentas con un tiempo limitado y el presupuesto te lo permite, te recomendamos contratar a profesionales del diseño.

Por razones económicas puedes sentir la tentación de pedirle al personal de tu organización que le dé formato al informe. Pero un diseño gráfico profesional puede marcar una gran diferencia en el aspecto del producto final y por lo tanto en el impacto que podrá alcanzar.

Las personas que se encarguen del diseño (ya sean de tu organización o contratadxs) deben ser capaces de:

¿Qué necesitarás aportarles a quienes se encarguen del diseño?

Recuerda que estarás trabajando con profesionales del diseño, que no necesariamente conocen las temáticas de las mujeres ni tampoco los resultados de la investigación, sobre todo si son personas contratadas y que no forman parte de tu organización.

Comunícales qué elementos del informe son importantes para ti y cuál es tu audiencia. Ellxs te sugerirán formas de destacar esos elementos y de hacer que todo el producto resulte atractivo a lxs usuarixs.

Cuando hayas creado un conjunto de productos informativos más breves, no olvides vincularlos entre sí:

También es importante que el personal que hizo la investigación se involucre en este estadio del proceso, para garantizar que todos los productos derivados sean consistentes con los resultados de la investigación.

Una vez que hayas completado el diseño y la presentación del informe de investigación en su versión final, asegúrate de volver a enviar a traducir cualquier modificación que se haya producido en la terminología o el contenido.

Si además creaste productos breves, una vez que estén diseñados y listos para ser difundidos también necesitarás contar con copias en los idiomas a los que se tradujo el informe. Las traducciones deben ser lo suficientemente claras como para que quien se encarga del diseño pueda elaborar los productos aun si no habla el idioma en que están escritos.

Una vez completadas las traducciones, asegúrate de que una persona que sea hablante nativa del/los idioma/s que corresponda/n las revise, antes de difundirlas.

7. Sintetiza los resultados de la investigación

• 2 - 3 meses

• 1 persona (o más) de investigación

• 1 Editor (editor web o si crea un producto en línea)

• Personal o empresa de diseño

• Traductores, de ofrecer encuesta en varios idiomas

• Lista de los espacios en línea para la difusión

7. Sintetiza los resultados de la investigación

9. Haz incidencia y cuéntale al mundo

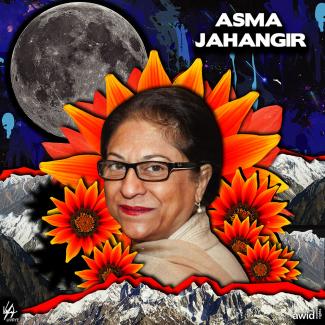

Asma était une militante pakistanaise des droits humains, une critique courageuse de l'ingérence de l'armée dans la politique et une défenseure acharnée de la primauté du droit.

Elle a été la présidente fondatrice de la Commission des droits de l'homme du Pakistan, un groupe indépendant ainsi qu’administratrice de l'International Crisis Group. Elle a remporté des prix internationaux et a été rapporteuse des Nations Unies sur les droits de l'homme et les exécutions extrajudiciaires.

Ses collègues et ami-e-s de l’AWID se souviennent d'elle avec affection

« Grâce à sa vie, Asma a réécrit l'histoire que beaucoup d'entre nous ont racontée en tant que femmes. Asma a changé le monde. Elle l'a changé au Pakistan et elle l'a changé dans notre imaginaire. »

Los datos se procesarán para fines estadísticos y así arrojar luz sobre el estado de la dotación de recursos para los movimientos feministas de todo el mundo, y solo se exhibirán de forma desglosada. AWID no divulgará información acerca de ninguna organización en particular ni publicará información que permita identificar a una organización por su ubicación o características sin el consentimiento acreditado de dicha organización.

En tant que féministes luttant pour la justice de genre, la paix, la justice économique, sociale et environnementale, nous savons qu'il n'existe pas de recette miracle, mais plutôt un éventail de possibilités qui peuvent faire changer les choses, et qui les font changer.

Cet éventail d’options est aussi diversifié que nos mouvements et les communautés dans lesquelles nous vivons et nous luttons.

Avant de vous présenter quelques-unes de ces propositions féministes pour un autre monde, voici les principes qui encadrent nos propositions :

Nous croyons qu'il ne doit pas y avoir un seul modèle pour tous, et que chacun-e doit avoir le droit de revendiquer et de contribuer à la construction d'un autre monde possible, comme le formule le slogan du Forum social mondial.

Cela inclut le droit de participer à la gouvernance démocratique et d'influer sur son avenir, politiquement, économiquement, socialement et culturellement.

L'autodétermination économique permet aux peuples de prendre le contrôle de leurs ressources naturelles et d'utiliser ces ressources pour atteindre leurs propres objectifs ou pour un usage collectif. En outre, le pouvoir d’agir des femmes dans la sphère économique est fondamental pour atténuer le caractère souvent cyclique de la pauvreté, le déni de l'éducation, de la sécurité et de la sûreté.

Le principe de l'égalité réelle est énoncé dans la Convention sur l'élimination de toutes les formes de discrimination à l'égard des femmes (CEDAW) et d'autres instruments internationaux relatifs aux droits humains. Ce principe est fondamental pour le développement et la transformation vers une économie juste, car il affirme que tous les êtres humains naissent libres et égaux.

La non-discrimination fait partie intégrante du principe d'égalité, qui veille à ce que personne ne soit privé de ses droits en raison de facteurs tels que la race, le sexe, la langue, la religion, l'orientation sexuelle, l'identité sexuelle, une opinion politique ou autre, l’origine nationale ou sociale, la fortune ou la naissance.

La dignité inhérente à toute personne sans distinction doit être maintenue et respectée. Alors que les États doivent veiller à l'utilisation d’un maximum de ressources disponibles pour la réalisation des droits humains, le fait d’exiger ces droits et la dignité est un enjeu clé pour la lutte de la société civile et la mobilisation populaire.

Ce principe, mis en œuvre par les efforts coordonnés visant à transformer les institutions injustes, soutient le rétablissement de l’équilibre entre la « participation » (entrées) et la « distribution » (sorties), lorsque celui-ci est rompu.

Il permet de poser des limites à l'accumulation monopolistique de capital et d'autres abus liés à la propriété. Ce concept est fondé sur un modèle économique qui repose sur l'équité et la justice.

Pour changer les choses, nous avons besoin de réseaux féministes solides et diversifiés. Nous avons besoin de mouvements qui renforcent la solidarité du niveau personnel au niveau politique, du niveau local au niveau global, et inversement.

Construire le pouvoir collectif grâce aux mouvements permet de convertir la lutte pour les droits humains, l'égalité et la justice en une force politique pour le changement qui ne peut être ignorée.

« Seuls les mouvements sont en mesure de créer des changements durables à des niveaux que la politique et les lois seules ne permettraient pas d’atteindre. »

Pour en savoir plus sur ce sujet, consulter S. Batliwala, 2012 Changer leur monde. Mouvements féministes, concepts et pratiques.

At the time of her death, following a short but aggressive battle with cancer, Deborah was the Chief Communication and Engagement Officer at the Women’s Funding Network (WFN).

Deborah also worked for the Global Fund for Women from 2008 to 2017. Deborah was extremely loved and respected by board, staff, and partners of Global Fund for Women.

Kavita Ramdas, former CEO of the Global Fund for Women aptly noted that Deborah was “a small package exploding with warmth, generosity, intelligence, style, and a passionate commitment to fusing beauty with justice. She understood the power of story. The power of women’s voice. The power of lived experience. The power of rising from the ashes and telling others it was possible. And, still we rise.”

Musimbi Kanyoro, the present CEO of the Global Fund for Women, added, “We have lost a sister and her life illuminates values that unite and inspire us all. As we all come together to mourn Deborah’s passing, let us remember and celebrate her remarkable, bold, and passionate life.”