Parveen Rehman

Women human rights defenders (WHRDs) worldwide defend their lands, livelihoods and communities from extractive industries and corporate power. They stand against powerful economic and political interests driving land theft, displacement of communities, loss of livelihoods, and environmental degradation.

Extractivism is an economic and political model of development that commodifies nature and prioritizes profit over human rights and the environment. Rooted in colonial history, it reinforces social and economic inequalities locally and globally. Often, Black, rural and Indigenous women are the most affected by extractivism, and are largely excluded from decision-making. Defying these patriarchal and neo-colonial forces, women rise in defense of rights, lands, people and nature.

WHRDs confronting extractive industries experience a range of risks, threats and violations, including criminalization, stigmatization, violence and intimidation. Their stories reveal a strong aspect of gendered and sexualized violence. Perpetrators include state and local authorities, corporations, police, military, paramilitary and private security forces, and at times their own communities.

AWID and the Women Human Rights Defenders International Coalition (WHRD-IC) are pleased to announce “Women Human Rights Defenders Confronting Extractivism and Corporate Power”; a cross-regional research project documenting the lived experiences of WHRDs from Asia, Africa and Latin America.

"Women Human Rights Defenders confronting extractive industries: an overview of critical risks and Human Rights obligations" is a policy report with a gender perspective. It analyses forms of violations and types of perpetrators, quotes relevant human rights obligations and includes policy recommendations to states, corporations, civil society and donors.

"Weaving resistance through action: Strategies of Women Human Rights Defenders confronting extractive industries" is a practical guide outlining creative and deliberate forms of action, successful tactics and inspiring stories of resistance.

The video “Defending people and planet: Women confronting extractive industries” puts courageous WHRDs from Africa, Asia, and Latin America in the spotlight. They share their struggles for land and life, and speak to the risks and challenges they face in their activism.

Challenging corporate power: Struggles for women’s rights, economic and gender justice is a research paper outlining the impacts of corporate power and offering insights into strategies of resistance.

AWID acknowledges with gratitude the invaluable input of every Woman Human Rights Defender who participated in this project. This project was made possible thanks to your willingness to generously and openly share your experiences and learnings. Your courage, creativity and resilience is an inspiration for us all. Thank you!

للجنسانيّة تدفّقات متعدّدة ومتبدّلة كحال الغمد الملتهب بين فخذَيّ

Upasana est un·e illustrateurice et artiste non binaire basé·e à Kolkata, en Inde. Son travail explore l'identité et les récits personnels en partant d’un vestige visuel ou d’une preuve des contextes avec lesquels iel travaille. Iel est particulièrement attiré·e par les motifs qui, selon Upasana, communiquent des vérités complexes sur le passé, le présent et l'avenir. Quand Upasana n'est pas en train de dessiner, iel organise et dirige un centre d'art communautaire queer et trans dans la ville.

Explore these projects put together by AWID teams to promote feminist advocacy and perspectives.

Hakima Abbas, AWID

"Estamos utilizando las herramientas que tenemos para compartir nuestra resistencia, nuestras estrategias y continuar edificando nuestro poder para actuar y crear nuevos mundos valientes y justos"

In short, yes! AWID is currently working with an Accessibility Committee to ensure that the Forum is as accessible as possible. We are also conducting an accessibility audit of the Forum venue, surrounding hotels and transportation. Detailed information about accessibility at the AWID Forum will be available in this section before the registration opens. Meanwhile, for any questions please contact us.

Contenido relacionado

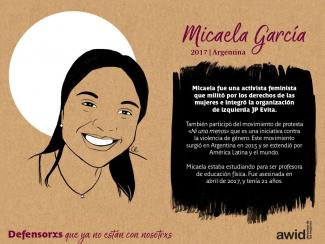

BBC Mundo: El terrible asesinato de la joven Micaela García que conmociona a Argentina

TeleSUR: América Latina, la región con más violencia hacia la mujer

Tonya Haynes, CAISO

Angelique V. Nixon, CAISO

سنعيد التواصل مع الشركاء/ الشريكات السابقين/ات لضمان احترام الجهود السابقة. إذا تغيرت معلومات الاتصال الخاصة بك منذ آخر عملية للمنتدى، فيرجى تحديثنا حتى نتمكن من الوصول إليك.