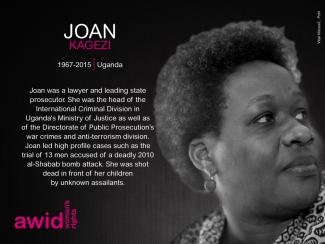

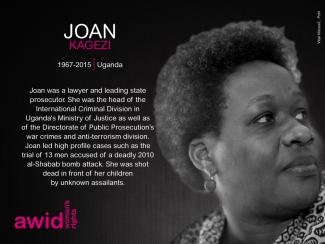

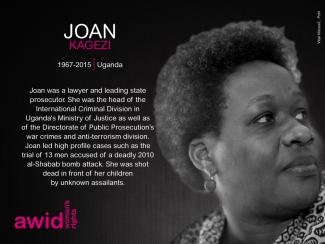

Joan Kagezi

The “Where is the Money?” #WITM survey is now live! Dive in and share your experience with funding your organizing with feminists around the world.

Learn more and take the survey

Around the world, feminist, women’s rights, and allied movements are confronting power and reimagining a politics of liberation. The contributions that fuel this work come in many forms, from financial and political resources to daily acts of resistance and survival.

AWID’s Resourcing Feminist Movements (RFM) Initiative shines a light on the current funding ecosystem, which range from self-generated models of resourcing to more formal funding streams.

Through our research and analysis, we examine how funding practices can better serve our movements. We critically explore the contradictions in “funding” social transformation, especially in the face of increasing political repression, anti-rights agendas, and rising corporate power. Above all, we build collective strategies that support thriving, robust, and resilient movements.

Create and amplify alternatives: We amplify funding practices that center activists’ own priorities and engage a diverse range of funders and activists in crafting new, dynamic models for resourcing feminist movements, particularly in the context of closing civil society space.

Build knowledge: We explore, exchange, and strengthen knowledge about how movements are attracting, organizing, and using the resources they need to accomplish meaningful change.

Advocate: We work in partnerships, such as the Count Me In! Consortium, to influence funding agendas and open space for feminist movements to be in direct dialogue to shift power and money.

Life expectancy of a trans and travesti person in Argentina is 37 years old - the average age for the general population is 77.

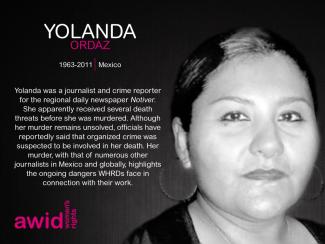

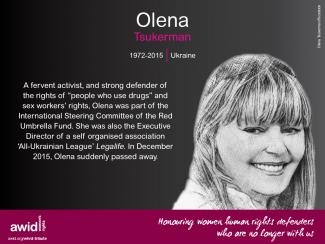

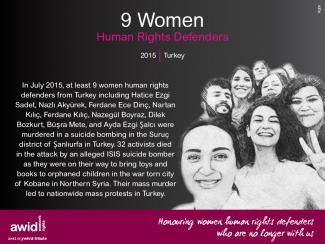

These 21 Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRDs) worked as journalists and more widely in the media sector in Mexico, Colombia, Fiji, Libya, Nepal, United States, Nicaragua, Philippines, Russia, Germany, France, Afghanistan, and the United Kingdom. 17 of them were murdered and in one case the cause of death is still unclear. On this World Press Freedom Day, please join us in commemorating the life and work of these women by sharing the images below with your colleagues, friends and networks using the hashtags #WPFD2016 and #WHRDs.

The contributions of these women were celebrated and honoured in our Tribute to Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRDs) Who Are No Longer With Us.

Please click on each image below to see a larger version and download as a file

The COVID-19 pandemic showed the world how important essential workers are. We’re talking about cleaners, nurses, paramedics, domestic workers, transport workers, grocery shop workers, among others. Their work is to tend to and guarantee the wellbeing of others, and they make our economies function.

But while they take care of us…

In 2013, we published three global reports. These reports confirm that women’s rights organizations are doing the heavy lifting to advance women’s rights and gender equality by using diverse, creative and long-term strategies, all while being underfunded.

Our 2010 global survey showed that the collective income of 740 women’s organizations around the world totaled only USD 104 million. Compare this with Greenpeace International, one organization with a 2010 budget of USD 310 million1. Imagine the impact these groups could have if they were able to access all the financial resources they need and more?

AWID’s WITM research has catalyzed increased funding for women’s rights organizing. WITM research was a driving force behind the Catapult crowdfunding platform, which has raised USD 6.5 million for women’s rights. The Dutch Government cited WITM research as a reason for its unprecedented MDG 3 Fund of EU 82 million. WITM research has also led to the creation of several new funds: FRIDA – The Young Feminist Fund, the Indigenous Women’s Fund, Fundo Elas, the Mediterranean Women’s Fund and the Rita Fund.

While the WITM research has shed important light on the global funding landscape, AWID and partners have identified the need to dig deeper, to analyze funding trends by region, population and issue. In response, organizations are now using AWID’s WITM research methodology to do their own funding trends analyses. For example, in November 2013, Kosova Women’s Network and Alter Habitus – Institute for Studies in Society and Culture published Where is the Money for Women’s Rights? A Kosovo Case Study.

At the same time, AWID continues to collaborate with partners in Where is the Money for Indigenous Women’s Rights (with International Indigenous Women’s Forum and International Funders for Indigenous Peoples) and our upcoming Where is the Money for Women’s Rights in Brazil? (with Fundo Elas).

Several organizations have also conducted their own independent funding trends research, deepening their understanding of the funding landscape and politics behind it. For example, the South Asian Women’s Fund was inspired by AWID’s WITM research to conduct funding trends reports for each country in South Asia, as well as a regional overview. Other examples of research outside of AWID include the collaboration between Open Society Foundations, Mama Cash, and the Red Umbrella Fund to produce the report Funding for Sex Workers Rights, and the first-ever survey on trans* and intersex funding by Global Action for Trans* Equality and American Jewish World Service.

There are varied conceptualizations about the commons notes activist and scholar Soma Kishore Parthasarathy.

Conventionally, they are understood as natural resources intended for use by those who depend on their use. However, the concept of the commons has expanded to include the resources of knowledge, heritage, culture, virtual spaces, and even climate. It pre-dates the individual property regime and provided the basis for organization of society. Definitions given by government entities limit its scope to land and material resources.

The concept of the commons rests on the cultural practice of sharing livelihood spaces and resources as nature’s gift, for the common good, and for the sustainability of the common.

Under increasing threat, nations and market forces continue to colonize, exploit and occupy humanity’s commons.

In some favourable contexts, the ‘commons’ have the potential to enable women, especially economically oppressed women, to have autonomy in how they are able to negotiate their multiple needs and aspirations.

Patriarchy is reinforced when women and other oppressed genders are denied access and control of the commons.

Therefore, a feminist economy seeks to restore the legitimate rights of communities to these common resources. This autonomy is enabling them to sustain themselves; while evolving more egalitarian systems of governance and use of such resources. A feminist economy acknowledges women’s roles and provides equal opportunities for decision-making, i.e. women as equal claimants to these resources.