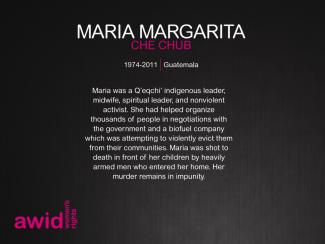

Maria Margarita Che Chub

The Human Rights Council (HRC) is the key intergovernmental body within the United Nations system responsible for the promotion and protection of all human rights around the globe. It holds three regular sessions a year: in March, June and September. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is the secretariat for the HRC.

Debating and passing resolutions on global human rights issues and human rights situations in particular countries

Examining complaints from victims of human rights violations or activist organizations on behalf of victims of human rights violations

Appointing independent experts (known as “Special Procedures”) to review human rights violations in specific countries and examine and further global human rights issues

Engaging in discussions with experts and governments on human rights issues

Assessing the human rights records of all UN Member States every four and a half years through the Universal Periodic Review

AWID works with feminist, progressive and human rights partners to share key knowledge, convene civil society dialogues and events, and influence negotiations and outcomes of the session.

Ces 21 Défenseuses des Droits humains (WHRDs) ont travaillé en tant que journalistes ou plus généralement dans le domaine des médias au Mexique, en Colombie, aux Îles Fidji, en Lybie, au Népal, aux États-Unis, au Nicaragua, aux Philippines, en Russie, en Allemagne, en France, en Afghanistan et au Royaume-Uni. 17 d'entre elles ont été assassinées et les causes de la mort de l’une d’elles restent obscures. Pour cette Journée mondiale de la liberté de la presse, joignez-vous à nous pour commémorer la vie et le travail de ces femmes. Faites circuler ces portraits auprès de vos collègues, vos ami-e-s et dans vos réseaux. Partagez-les en utilisant les mots-clés #WPFD2016 et #WHRDs.

Les contributions de ces femmes ont été célébrées et honorées dans notre Hommage en ligne aux défenseuses qui ne sont plus parmi nous.

Cliquez sur chaque image pour voir une version plus grande ou pour télécharger le fichier.

Para fortalecer nuestra voz y poder colectivos para obtener más y mejor financiamiento para las organizaciones feministas, por los derechos de las mujeres y de las personas LBTQI+ y demás organizaciones aliadas de todo el mundo.

Liliana était enseignante argentine, tisseuse et également une écrivaine reconnue.

Sa trilogie « La saga des confins » a reçu plusieurs prix. Son œuvre est la seule dans le domaine littéraire fantastique à avoir eu recours et ré-imaginé la mythologie autochtone sud-américaine.

L’engagement de Liliana envers le féminisme s’est exprimé à travers les voix féminines diverses, riches et fortes de ses écrits, et en particulier dans le cadre de ceux à destination du jeune public. Elle a également pris position publiquement en faveur de l'avortement, de la justice économique et de l’égalité de genre.

Manal Tamimi es una activista y defensora de los derechos humanos palestina. Tiene cuatro hijxs y posee una maestría en derecho humanitario internacional. Debido a su activismo, fue arrestada en tres ocasiones y sufrió más de una herida, incluso balas explosivas reales, algo prohibido en el plano internacional. Su familia también es blanco de agresiones: sus hijxs han sido arrestados y sufrido heridas con munición activa más de una vez. El último hecho fue un intento de asesinato contra su hijo Muhammad, quien recibió un disparo en el pecho cerca del corazón, unas semanas después de ser liberado de las prisiones de la ocupación en las que había estado dos años. Su filosofía de vida: si tengo que pagar un precio por ser palestina y no por un delito que haya cometido, me niego a morir callada.

The 3 Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRDs) from the Pacific we are featuring in this year's Online Tribute have worked in the media, campaigned for disability rights and advocated for women’s rights. Their contributions are missed and we honor them in this Tribute. Please join AWID in commemorating these WHRDs, their work and legacy by sharing the memes below with your colleagues, networks and friends and by using the hashtags #WHRDTribute.

Please click on each image below to see a larger version and download as a file

Le 11 juillet 2024, nous avons eu une conversation étonnante avec de grandes féministes sur l'état de l'écosystème du financement et le pouvoir du recherche « Où est l'argent ? ».

Un merci spécial à Cindy Clark (Thousand Currents), Sachini Perera (RESURJ), Vanessa Thomas (Black Feminist Fund), Lisa Mossberg (SIDA) et Althea Anderson (Fondation Hewlett).

N'oubliez pas que l'enquête restera ouverte jusqu'au 31 août 2024 !

Juana was an Indigenous Mayan Ixil, professional nurse and coordinator of the Farmers’ Development Committee (Comité de Desarrollo Campesino – CODECA).

CODECA is a human rights organisation of Indigenous farmers dedicated to promoting land rights and rural development for Indigenous families) in the Nebaj Quiché micro-region. She first joined CODECA as a member of its youth branch (Juventud de CODECA). At the time of her death had been elected to be part of the Executive Committee of the Movement for the Liberation of Peoples (MLP).

Juana’s body was found by neighbours by a small river on the road near Nebaj and Acambalam Village, Guatemala. According to CODECA, her body showed signs of torture.

This journal edition in partnership with Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research, will explore feminist solutions, proposals and realities for transforming our current world, our bodies and our sexualities.

Este kit incluye ejemplos de mensajes para ser utilizados en Twitter, Facebook y LinkedIn, como así también imágenes que puedes usar para acompañar a estos mensajes.

La utilización de este kit es muy simple. Solo tienes que seguir estos pasos:

Descarga aquí tus imágenes favoritas:

Twitter

Facebook

Instagram

Combina estos mensajes con las imágenes para Twitter

Yo voy al #AWIDForum. Es EL lugar para conectar con los movimientos por los derechos de las mujeres y la justicia social ¡Únete a mi!: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

¡Ya quiero re-imaginar los #FuturosFeministas c/ otrxs activistas x los DD. de las mujeres y la justicia social en el #AWIDForum! Únete: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Me entusiasma poder asistir al Foro de AWID el próximo mes de mayo ¡Ahora ya podemos registrarnos! ¡Únete a mi! http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Se encuentra abierta la inscripción para participar del #AWIDForum! en Costa do Sauípe, Brasil, 8-11 de sept 2016: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Únete al #AWIDForum, un encuentro histórico global de activistas x los derechos de las mujeres y la justicia social: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Únete al #AWIDForum para celebrar los logros de nuestros movimientos y las lecciones aprendidas para seguir avanzando http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

El #AWIDForum, no es solo un evento sino una oportunidad para confrontar la opresión y promover el avance de la justicia: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Únete al #AWIDForum para celebrar, pensar estrategias y renovar nuestros movimientos y a nosotrxs mismxs: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Construyamos juntxs los #FuturosFeministas. Inscríbete al #AWIDForum. Costa do Sauípe, Brasil: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Únete a nosotrxs para re-imaginar y crear juntxs los #FuturosFeministas en el #AWIDForum. Inscríbete: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

#FuturosFeministas: aprovecha el momento en el #AWIDForum para promover nuestras visiones de un mundo mejor: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Seremos 2000 activistas de movimientos sociales en el #AWIDForum, pensando estrategias para nuestros #FuturosFeministas http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Somos mucho más que una sola lucha. Únete a nosotrxs en el #AWIDForum: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Únete al #AWIDForum, un espacio para pensar estrategias entre movimientos y hacer uso de nuestro poder colectivo: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Movilicemos la solidaridad y el poder colectivo entre movimientos sociales en el #AWIDForum: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Rompamos el aislamiento entre nuestros movimientos. Re-imaginemos y creemos juntxs nuestros futuros en el #AWIDForum: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Solidaridad es un verbo. Pongámosla en acción en el #AWIDForum: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Donantes se comprometen con los derechos de las mujeres y los movimientos sociales en el #AWIDForum: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Los medios de comunicación y los movimientos amplifican los #FuturosFeministas en el #AWIDForum: http://forum.awid.org/forum16/es

Combina estos mensajes con las imágenes para Facebook

Estos mensajes pueden ser usados en Twitter también vía mensaje privado directo, ya que allí no hay límites de carácteres.

Descarga tus imágenes favoritas para usar en Instagram

Kagendo es cariñosamente recordada por su familia y amigxs como una férrea activista feminista africana, artista y realizadora cinematográfica

Dedicó más de 20 años a defender los derechos y la dignidad de las personas LGBTIQ y de género no normativo de África. Lxs colegas de Kagendo la recuerdan como alguien con una personalidad jovial, convicciones férreas y amor a la vida. Kagendo murió por causas naturales en su hogar de Harlem, el 27 de diciembre de 2017.

Al producirse su fallecimiento, la escritora y activista keniata Shailja Patel destacó «el compromiso de toda la vida de Kagendo para establecer una relación entre todas las formas de opresión, mostrando de qué manera el colonialismo alentó la homofobia en el continente africano, para convertir así a Kenia en un país donde las personas queer y las mujeres libres puedan vivir y progresar».

Por favor consulta la Convocatoria de Actividades, incluida la sección «Lo que necesitas saber».

مريم مكيوي مخرجة أفلام ومصورة من الإسكندرية تعيش وتعمل في برلين.