Co-Creating Feminist Realities

What are Feminist Realities?

Feminist Realities are the living, breathing examples of the just world we are co-creating. They exist now, in the many ways we live, struggle and build our lives.

Feminist Realities go beyond resisting oppressive systems to show us what a world without domination, exploitation and supremacy look like.

These are the narratives we want to unearth, share and amplify throughout this Feminist Realities journey.

Transforming Visions into Lived Experiences

Through this initiative, we:

-

Create and amplify alternatives: We co-create art and creative expressions that center and celebrate the hope, optimism, healing and radical imagination that feminist realities inspire.

-

Build knowledge: We document, demonstrate & disseminate methodologies that will help identify the feminist realities in our diverse communities.

-

Advance feminist agendas: We expand and deepen our collective thinking and organizing to advance just solutions and systems that embody feminist values and visions.

-

Mobilize solidarity actions: We engage feminist, women’s rights and gender justice movements and allies in sharing, exchanging and jointly creating feminist realities, narratives and proposals at the 14th AWID International Forum.

The AWID International Forum

As much as we emphasize the process leading up to, and beyond, the four-day Forum, the event itself is an important part of where the magic happens, thanks to the unique energy and opportunity that comes with bringing people together.

We expect the next Forum to:

-

Build the power of Feminist Realities, by naming, celebrating, amplifying and contributing to build momentum around experiences and propositions that shine light on what is possible and feed our collective imaginations

-

Replenish wells of hope and energy as much needed fuel for rights and justice activism and resilience

-

Strengthen connectivity, reciprocity and solidarity across the diversity of feminist movements and with other rights and justice-oriented movements

Learn more about the Forum process

We are sorry to announce that the 14th AWID International Forum is cancelled

Given the current world situation, our Board of Directors has taken the difficult decision to cancel Forum scheduled in 2021 in Taipei.

Related Content

Мы распределяем деньги среди наших грантополучающих партнерок(-ров) и являемся феминистским и/или женским фондом – можем ли мы участвовать в опросе?

Нет, мы высоко ценим вашу работу, но в данный момент мы не просим откликов от женских и феминистских фондов. Мы будем рады, если вы поделитесь информацией об опросе со своими партнерками(-рами) и контактами внутри феминистской сети.

FRMag - Resistance Series

Feminist Resistance Series

Posso aceder a e realizar o inquérito no meu telemóvel?

Sim, o inquérito pode ser acedido através de um smartphone.

ours chapter 5

Chapter 5

Anti-Rights Tactics, Strategies, and Impacts

Anti-rights actors adopt a double strategy. As well as launching outright attacks on the multilateral system, anti-rights actors also undermine human rights from within. Anti-rights actors engage with the aim of co-opting processes, entrenching regressive norms, and undermining accountability.

هل ستكون لي الفرصة بمشاركة افكاري بأمور لا تغطيها أسئلة الاستطلاع؟

نعم. ندعوكم/ن لمشاركتنا بالأمور التي تجدونها مهمة بالنسبة لكم/ن عن طريق الإجابة على الأسئلة المفتوحة في نهاية الاستطلاع.

Snippet Kohl - Plenary | She is on her way: Alternatives, feminisms and another world

with Dr. Vandana Shiva, Dr. Dilar Dirik, and Nana Akosua Hanson.

Является ли мое участие конфиденциальным?

Да. Ваши ответы будут удалены по окончании обработки и анализа данных и будут использованы исключительно в исследовательских целях. Данные НИКОГДА не будут переданы за пределы AWID и будут обрабатываться только сотрудниками AWID и консультантками(-тами), работающими с нами над проектом «Где деньги?». Для нас ваша конфиденциальность и безопасность– приоритет. С нашей политикой конфиденциальности можно подробно ознакомиться здесь.

Desejam recolher quantas respostas ao questionário?

O nosso objetivo é alcançar um total de 2000 respostas, quase o dobro do último questionário WITM em 2011.

Lindiwe Rasekoala | Snippet AR

لينديوي راسيكوالا مدربة حياتية، متخصصة في التدريب على العلاقات الحميمة. إنها متخصصة بالصحة الجنسية ولديها مساهمات في هذا الموضوع عبر الإنترنت. من خلال تجاربها الخاصة وأساليب البحث غير التقليدية التي تنتهجها، تعتقد لينديوي أنها تستطيع سد الفجوة التعليمية، فيما خص الصحة الجنسية وإشكالية الوصول إلى المعلومات حول الموضوع. لها العديد من المساهمات في البرامج الإذاعية والتلفزيونية، وقد أكملت تعليمها كمدرب مع تحالف المدربين المعتمدين CCA. تتمثل مهمة لينديوي في كسر الحواجز التي تحول دون قيام المحادثات حول الصحة الجنسية، وتمكين زملائها من تحقيق فهم أكبر لأنفسهم، حتى يتمكنوا من تجربة نمط حياة وعلاقات أكثر صحية وتكامليّة.

Disintegration | Content Snippet AR

وصلتني رسالة يوم الأربعاء

مصحوبة بعنوانٍ على ظهرها.

الخامسة مساءً، اليوم

خطّ كتابة الدعوة –

متحفّظ وجاف –

رأيته خمس مرّات في خمس سنوات.

جسدي مُستنفَر،

محموم.

أحتاج لمضاجعة نفسي أوّلًا.

المدُّ عالٍ الليلة

وأنا

أنتشي.

أريدُ إبطاءَ كلَّ شيء،

واستطعام الوقت والفراغ،

أن أحفرهما

في الذاكرة.

*

لم آتِ أبدًا إلى هذا الجزء من البلدة.

الأماكن المجهولة تثيرني،

[كذلك] الطريقة التي تقاوم بها الأشلاء والعروق والعظام

الاضمحلال،

مصيرهم غامض.

عند الباب أعيدُ التفكير.

الرواق قاتم السواد

يجعلني أتوقّف.

على الناحية الأخرى،

مثل اللعنة، يُفتَح باب

من الروائح والألوان

على عَصْرٍ مُشمس.

النسيم

يجعل شعري يرقص،

يثير فضوله،

يدفعه للحركة.

أسمعُ أزيزَ الكرسي المتحرّك،

يشكّل الظلال.

عندها أراهم:

وجه فهد

وجسدٌ مثل جسدي

وأجِدني راغبة بكليهما

مرّة أخرى.

يقترب المخلوق منّي.

إيماءاتهم تكتب جملة؛

كلّما اقتربت منهم،

أتبيّن تفاصيلها:

ذبول، لحم، غِبطة

بأمر ٍمنهم، تزحف الكرمة

التي تغطّي الرُواق

مُعانقةً الصخور الدافئة

وتتسلّق الحائط كالأفعى.

لقد أصبح فعلًا،

«أن تقفز»،

أُعيدَ توجيهي عندما أشارت مخالبهم

نحو سرير الكرم في المنتصف.

أسمع العجلات خلفي،

ثم أسمع ذلك الصوت.

يُدوي

بشكلٍ لا مثيل له.

أجنحتهم الطويلة السوداء

ترتفع نحو السقف

ثم تندفع للأمام.

عينا الهرّة تفحص كلّ تفصيلة،

كلّ تغيّر،

كلّ تَوق.

هل يمكن أن تُذيب الرغبة عضلاتك؟

هل يمكن أن تكون أحلى من أقوى المهدّئات؟

فهدٌ يخيط العالم،

عبرَ اختلافاتنا،

غازلًا الدانتيل حول ركبتيَّ.

هل يمكن للرغبة أن تسحق تباعُد العالم،

أن تكثّف الثواني؟

مازالوا يقتربون،

تلتقي عين الفهد بعين الإنسان،

تتنشّق الهواء،

تُحوِّل الجسد إلى

إلحاح.

يخفقون بأجنحتهم للأسفل.

هائجة،

تلتفّ الكرمة حول خصري/ خسارتي.

لسانهم يرقّق الوقت،

تتبدّل الآراء،

يُسكِّن، بسحرهم،

ما يشتعل أسفل [السطح].

أرى العالم فيك، والعالم مُنهَك.

ثم يتوسّلون:

دعيني أقتات عليك.

Snippet - CSW69 - OURs & friends - EN

OURs & friends at the Feminist Solidarity Space

✉️ By invitation only

📅 Tuesday, March 11, 2025

🕒 2.00-4.00pm EST

🏢 Chef's Kitchen Loft with Terrace, 216 East 45th St 13th Floor New York

Organizer: Observatory on the Universality of Rights (OURs) Consortium

A Collective Love Print | Small Snippet AR

Snippet - Jobs and opportunities intro

If you’re looking to have an impact through your work in feminist, social justice and other non-profit organizations, we hope this page provides a start.

Here you will find open vacancies and call for applications from AWID and the Alliance for Feminist Movements, when available. Follow us on social media to be in the loop.

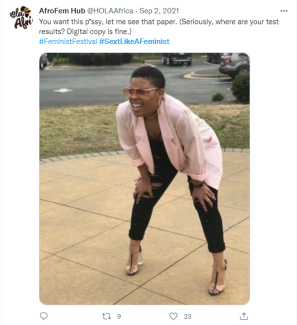

Sexting Like a Feminist: Humor in the Digital Feminist Revolution | Title Snippet AR

الصياغات النسوية للرسائل النصّية ذات المحتوى الجنسي: الدُّعابة الجنسانيّة في فضاء الثورة النسوية الرقمية

تشينيلو أونوالو

ترجمة مايا زبداوي

Snippet - WCFM With smart filtering - EN

With smart filtering for Who Can Fund Me? Database, you can search for funders based on:

Pleasure Garden

Pleasure Garden

The artwork is a photography and illustration collaboration between Siphumeze and Katia during lockdown. The work looks at black queer sex and plesure narratives, bondage, safe sex, toys, mental health and sex and many more. It was created to accompany the Anthology Touch.

Snippet - WITM Infographic annual budget - EN

In 2023, feminist and

women's rights organizations

had a median annual budget of $22,000

In contrast, over $1 billion went to three anti-rights groups 2021-2022, with funding for anti-gender networks still rising.1

1 Global Philanthropy Project, 2024