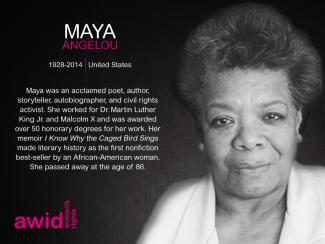

Maya Angelou

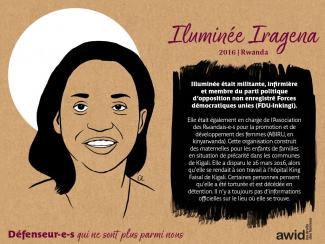

L’hommage se présente sous forme d’une exposition de portraits d’activistes du monde entier qui ne sont plus parmi nous qui ont lutté pour les droits des femmes et la justice sociale.

Cette année, tout en continuant à convoquer la mémoire de celleux qui ne sont plus parmi nous, nous souhaitons célébrer leur héritage et souligner les manières par lesquelles leur travail continue à avoir un impact sur nos réalités vécues aujourd’hui.

49 nouveaux portraits de féministes et de défenseur·e·s viennent compléter la gallerie. Bien que de nombreuses des personnes que nous honorons dans cet hommage sont décédé·e·s du fait de leur âge ou de la maladie, beaucoup trop d’entre iels ont été tué·e·s à cause de leur travail et de qui iels étaient.

Visiter notre exposition virtuelle

Les portraits de l'édition 2020 ont été illustrés par Louisa Bertman, artiste et animatrice qui a reçu plusieurs prix.

L’AWID tient à remercier nos membres, les familles, les organisations et les partenaires qui ont contribué à cette commémoration. Nous nous engageons auprès d’elleux à poursuivre le travail remarquable de ces féministes et défenseur·e·s et nous ne ménagerons aucun effort pour que justice soit faite dans les cas qui demeurent impunis.

« Ils ont essayé de nous enterrer. Ils ne savaient pas que nous étions des graines » - Proverbe mexicain

Le premier hommage aux défenseur-e-s des droits humains a pris la forme d’une exposition de portraits et de biographies de féministes et d’activistes disparu·e·s lors du 12e Forum international de l’AWID en Turquie. Il se présente maintenant comme une gallerie en ligne, mise à jour chaque année.

Depuis, 467 féministes et défenseur-e-s des droits humains ont été mis·es à l'honneur.

La montée de la droite dans nombre de pays et le déluge de coupes dans les financements frappent durement la société civile de la Majorité mondiale ; le génocide en cours à Gaza, l’intensification des conflits violents au Soudan, la crise climatique à de nombreux endroits de notre planète : nous faisons face à des fascismes qui reviennent en force et un ordre mondial de l’impunité.

Téléchargez le rapport annuel 2024

Ensemble, nous pouvons construire un monde où la justice, la libération et la bienveillance ne sont pas des aspirations, mais des réalités.

المستشفيات مؤسسات، ومواقع حيّة للرأسمالية، وما يحدث عندما يكون من المفترض أن يستريح شخصٌ ما ليس إلّا نموذجاً مصغّراً من النظام الأكبر.

Related Content

Front Line Defenders: Emilsen Manyoma Killed

ReliefWeb: A human rights defender killed every other day in 2017 in Colombia (between 1 and 23 January 2017)

Global Witness: Defenders of the Earth (2016 Report)

okayafrica.: Who is Killing Colombia's Black Human Rights Activists?

PBI Colombia: We will always accompany your work

Bitch Media: Don’t Touch My Crown: The failure of decapitation and the power of black women’s resistance

Inna es una activista y socióloga feminista queer. Posee muchos años de profundo compromiso con las luchas feministas y LGBTQI+, la educación en política y en procesos de organización de y para las mujeres migrantes, así como por la liberación de y la solidaridad con Palestina. Se incorporó a AWID en 2016 y cumplió diferentes funciones, la más reciente como Directora de Programas. Reside en Berlín (Alemania), creció en Haifa (Palestina/Israel), nació en San Petersburgo (Rusia), y ha puesto todo ese recorrido geográfico político y de resistencia a los colonialismos pasados y presentes al servicio del activismo feminista y la solidaridad transnacional.

Inna es autora de Women's Economic Empowerment: Feminism, Neoliberalism, and the State (Empoderamiento económico de las mujeres: Feminismo, neoliberalismo y Estado. Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), basado en la tesis que le valió un doctorado de la Universidad Humboldt de Berlín. Como académica, impartió cursos sobre globalización, producción de conocimientos, identidad y pertenencia. Inna posee una maestría en Estudios Culturales de la Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén. Integra la Junta de Jewish Voice for a Just Peace in the Middle East (Voces Judías por una Paz Justa en Medio Oriente, Alemania) y, con anterioridad, fue miembro de la Junta de +972 Advancement of Citizen Journalism (+972 Avance del Periodismo Ciudadano). Antes, Inna trabajó con la Coalición de Mujeres por la Paz y es una apasionada de la movilización de recursos para el activismo de base.

عندما يصبح عملنا المتجسّد مادةً ربحية في أيدي الأنظمة التي نسعى إلى إزالتها فلا عجب أنّ جنسانيّاتنا وملذّاتنا توضَع جانباً من جديد، لا سيّما أنّها ليست مُربِحة بما فيه الكفاية. لقد تساءلنا، في مواقف عدّة خلال إنتاج هذا العدد، ما الذي سيحدث إذا رفضنا مراعاة خدمات الرأسمالية الأساسية؟ لكن هل نجرؤ على هذا التساؤل وقد أنهكنا العالم؟ ربما يتمّ تجاهل جنسانيّاتنا بهذه السهولة لأنها لا تُعتَبَر أشكالاً من أشكال الرعاية. ربما ما نحتاجه هو أن نعيد تصوّر الملذّة كشكلٍ من أشكال الرعاية الجذرية، تكون أيضاً مناهضة للرأسمالية وللمؤسساتية.

Contenido relacionado

Norte Digital de Ciudad Juárez: Cerramos en protesta

La Jornada: Brazo del ‘cártel’ de Sinaloa ordenó asesinar a Miroslava Breach: FGE

BBC: Miroslava Breach, la periodista “incómoda” asesinada en México cuando llevaba a su hijo a la escuela

Marianne Mesfin Asfaw est une féministe panafricaine qui se consacre à la justice sociale et à la construction communautaire. Elle est titulaire d'une licence en études de genre et en relations internationales de l'Université de la Colombie-Britannique (UBC) et d'un master en études de genre et de droit de l'Université SOAS de Londres. Auparavant, elle travaillait dans l'administration universitaire et le soutien aux étudiant·e·s internationaux·ales, de même qu’à titre de chercheuse et d’animatrice dans des espaces féministes à but non lucratif. Elle a également travaillé et été bénévole auprès d'organisations non gouvernementales, notamment Plan International, dans des rôles administratifs. Avant d'occuper son poste actuel, elle a travaillé dans le soutien logistique et administratif à l'AWID. Elle est originaire d'Éthiopie, a grandi au Rwanda et est actuellement basée à Tkaronto/Toronto, au Canada. Elle aime lire, voyager et passer du temps avec sa famille et ses ami·e·s. Pendant les mois les plus chauds, on peut la trouver en train de se promener dans des quartiers familiers à la recherche de cafés et de librairies obscurs dans lesquels flâner.

Claudia is a feminist psychologist with a Masters degree in Development Equality and Equity. She has been a human rights activist for 30 years, and a women’s rights activist for the last 24.

Claudia works in El Salvador as the co-founder and Executive Director of Asociación Mujeres Transformando. For the past 16 years she has defended labour rights of women working within the textile and garment maquila sector. This includes collaborations to draft legislative bills, public policy proposals and research that aim to improve labour conditions for women workers in this sector. She has worked tirelessly to support organizational strengthening and empowerment of women workers in the textile maquilas and those doing embroidery piece-work from home.

She is an active participant in advocacy efforts at the national, regional and international levels to defend and claim labour rights for the working class in the global South from a feminist, anti-capitalist and anti-patriarchy perspective and class and gender awareness raising. She is a board member with the Spotlight Initiative and its national reference group. She is also part of UN Women’s Civic Society Advisory Group.

Related content

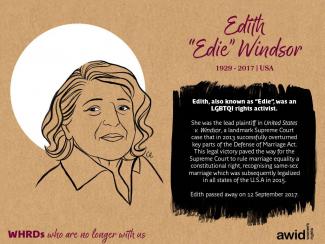

The Guardian: Edith Windsor, icon of gay rights movement, dies aged 88

Rolling Stone: Edith Windsor, Same-Sex Marriage Activist, Dead at 88

BBC: Edie Windsor: Gay rights trailblazer dies aged 88

The New Yorker: Postscript: Edith Windsor, 1929-2017

The Guardian: Goodbye, Edie Windsor. Thank you for never giving up

Love and Justice: Edith Windsor talks with Ariel Levy - The New Yorker Festival - The New Yorker (Video)

Remembering Edie Windsor (Video)

عزمي الوصول الى الذروة الجنسية، كفيلة بإيقاظ الأجداد من مثواهم الأخير وإعادتهم الى صفوف الثورة التقدميّة

Sanyu es una feminista que reside en Nairobi (Kenia). Ha dedicado los últimos 10 años a apoyar a los movimientos obreros, feministas y por los derechos humanos, promoviendo la rendición de cuentas empresarial, la justicia económica y la justicia de género. Ha trabajado con el Centro de Información sobre Empresas y Derechos Humanos, en International Women’s Rights Action Watch Asia y el Pacífico (IWRAW, Observatorio Internacional de los Derechos de las Mujeres) y la Iniciativa de Derechos Humanos de la Commonwealth. Posee una maestría en Leyes y Derechos Humanos y una licenciatura en Derecho de la Universidad de Nottingham. Sus escritos se han publicado en el Business and Human Rights Journal, Human Rights Law Review, y plataformas como Open Global Rights, Democracia Abierta, entre otras. En sus ratos libres, le gusta caminar por el bosque y perseguir mariposas.