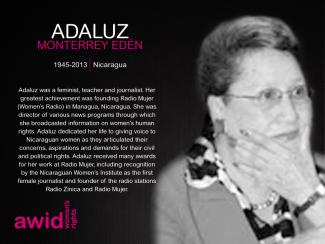

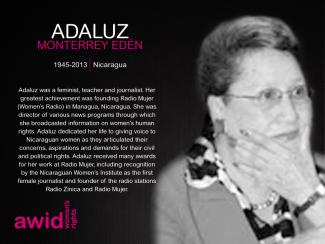

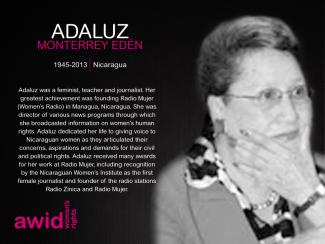

Adaluz Monterrey Eden

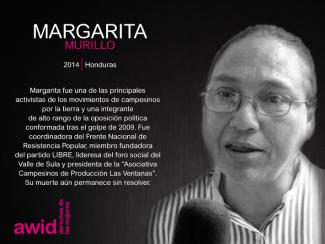

L’hommage se présente sous forme d’une exposition de portraits d’activistes du monde entier qui ne sont plus parmi nous qui ont lutté pour les droits des femmes et la justice sociale.

Cette année, tout en continuant à convoquer la mémoire de celleux qui ne sont plus parmi nous, nous souhaitons célébrer leur héritage et souligner les manières par lesquelles leur travail continue à avoir un impact sur nos réalités vécues aujourd’hui.

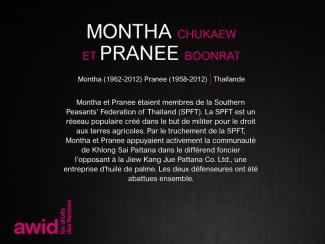

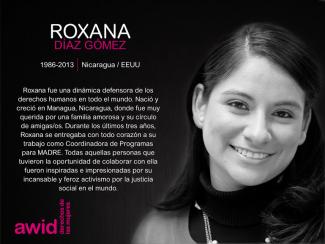

49 nouveaux portraits de féministes et de défenseur·e·s viennent compléter la gallerie. Bien que de nombreuses des personnes que nous honorons dans cet hommage sont décédé·e·s du fait de leur âge ou de la maladie, beaucoup trop d’entre iels ont été tué·e·s à cause de leur travail et de qui iels étaient.

Visiter notre exposition virtuelle

Les portraits de l'édition 2020 ont été illustrés par Louisa Bertman, artiste et animatrice qui a reçu plusieurs prix.

L’AWID tient à remercier nos membres, les familles, les organisations et les partenaires qui ont contribué à cette commémoration. Nous nous engageons auprès d’elleux à poursuivre le travail remarquable de ces féministes et défenseur·e·s et nous ne ménagerons aucun effort pour que justice soit faite dans les cas qui demeurent impunis.

« Ils ont essayé de nous enterrer. Ils ne savaient pas que nous étions des graines » - Proverbe mexicain

Le premier hommage aux défenseur-e-s des droits humains a pris la forme d’une exposition de portraits et de biographies de féministes et d’activistes disparu·e·s lors du 12e Forum international de l’AWID en Turquie. Il se présente maintenant comme une gallerie en ligne, mise à jour chaque année.

Depuis, 467 féministes et défenseur-e-s des droits humains ont été mis·es à l'honneur.

Tous nos rapports annuels sont accessibles sur notre site web.

للجنسانيّة تدفّقات متعدّدة ومتبدّلة كحال الغمد الملتهب بين فخذَيّ

Yes please. The world has changed since 2021 and we invite you to submit an activity that reflects your current realities and priorities.

We invite you to explore the Priority Areas and Stay Informed sections of our website, or use the search function to find information about the specific topics you are researching.

We particularly recommend that you explore our toolkit “Where is the Money for Women’s Rights” (WITM Toolkit). This is a Do-it-Yourself Research methodology to support individuals and organizations who want to conduct their own research on funding trends for a particular region, issue or population by adapting AWID’s research methodology.

Upasana est un·e illustrateurice et artiste non binaire basé·e à Kolkata, en Inde. Son travail explore l'identité et les récits personnels en partant d’un vestige visuel ou d’une preuve des contextes avec lesquels iel travaille. Iel est particulièrement attiré·e par les motifs qui, selon Upasana, communiquent des vérités complexes sur le passé, le présent et l'avenir. Quand Upasana n'est pas en train de dessiner, iel organise et dirige un centre d'art communautaire queer et trans dans la ville.

يعتبر المنتدى الدولي الخامس عشر لجمعية حقوق المرأة في التنمية حدثًا مجتمعيًا عالميًا ومساحة للتحول الشخصي الجذري. يجمع المنتدى، وهو اجتماع فريد من نوعه، الحركات النسوية وحقوق المرأة والعدالة الجندرية ومجتمع الميم عين والحركات الحليفة، بكل تنوعنا وإنسانيتنا، للتواصل والشفاء والازدهار. المنتدى هو المكان الذي تحتل فيه نسويات ونسويو الجنوب العالمي والمجتمعات المهمشة تاريخياً مركز الصدارة، حيث يضعون الاستراتيجيات مع بعضهم/ن البعض، مع الحركات الحليفة الأخرى، ومع المموّلين وصانعي السياسات بهدف تحويل السلطة، إقامة تحالفات استراتيجية، والدخول في عالم أفضل ومختلف.

عندما يجتمع الناس على نطاق عالمي، كأفراد وحركات، فإننا نولد قوة جارفة. انضموا إلينا في بانكوك، تايلاند في عام 2024. تعالوا وارقصوا وغنوا واحلموا وانهضوا معنا.

متى: 2-5 ديسمبر 2024

أين: بانكوك، تايلاند؛ وعلى الانترنت

من: ما يقرب الـ 2500 ناشط/ة نسوية من جميع أنحاء العالم يشاركون شخصيًا، و3000 يشاركون افتراضيًا

Segundo Diálogo de Alto Nivel sobre la Financiación para el Desarrollo

Las naciones ‘en desarrollo’ exhortaron a que se tuvieran en cuenta los desafíos globales así como las necesidades y posibilidades locales en la interacción con diferentes grupos (mujeres, jóvenes, personas con discapacidad, etc.) para abordar las temáticas identificadas en el Consenso de Monterrey.

Explore these projects put together by AWID teams to promote feminist advocacy and perspectives.

Le cinquième Dialogue de haut niveau sur le financement du développement, organisé les 7 et 8 décembre 2011, a marqué le début des discussions relatives au programme de développement de l’après-2015 et aux liens entre ce programme et le financement du développement. La conférence a accordé une attention particulière à la question de l’accroissement de l’aide au financement des OMD. Dans ses observations finales, le Secrétaire général a appelé les membres à commencer à réfléchir sur le cadre de développement de l’après-2015.

Hakima Abbas, AWID

"Estamos utilizando las herramientas que tenemos para compartir nuestra resistencia, nuestras estrategias y continuar edificando nuestro poder para actuar y crear nuevos mundos valientes y justos"

Additional consultation sessions on the Draft Outcome Document