The recent UK debates around the Gender Recognition Act create the illusion that one strand of feminism is inherently anti-trans: radical and lesbian feminism. So, let’s set the record straight: lesbians have always rebelled against gender binary and sexual repression. We have always been traitors to gender essentialism.

In truth, intimacy and solidarity with transgender folks and trans struggles for rights, justice and respect are central to our history and our roots, as feminists and lesbians. Let me offer some examples from the trajectory that has informed my own identity, experience and politics.

Monique Wittig, a feminist theorist and self-identified radical lesbian, argued in her formative essay, The Straight Mind (1979), that “lesbians are not women”. The category of woman, she explained, has a meaning only in relation to the category of man, within a heterosexual system of thought and economy. This is everything but gender binary thinking.

Audre Lorde opens her autobiography, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), with the words: “I have always wanted to be both man and woman”. She imagines the triangle of mother father child elongating into the triad of grandmother mother daughter, with her own self floating in either or both directions. Lorde’s fluidity here transcends not only patriarchal boundaries of gender, but also those of ancestry, generational lineage and time.

Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues (1992), a celebrated novel of great importance to lesbian culture, tells the story of Jess, a working-class butch, with a complicated and evolving relation with her gender identity. This book is full of love and respect for characters who are transgender, as well as those who do sex work. It celebrates femme and butch identities and culture, and fundamentally questions social norms and constraints of masculinity and femininity.

These are not exceptions. Yet, many people have come to believe that radical feminism inherently clashes with the rights, recognition and respect of trans people. Or, that to be a radical feminist means to reject the sex workers’ rights movements. In some feminist circles, being anti-trans, similarly to being anti-sex workers’ rights, is a practice of belonging. Being “radfem” – short for radical feminist – becomes a club. Belonging to this club comes with a set of ideological positions that may not be questioned, if you care to remain a member.

As a result, our legacy is manipulated and re-written, and we are left with a narrow, censored, twisted and largely transphobic version of radical and lesbian feminist theories and movements. Generations of feminists are thus ignorant of the revolutionary ideas, theories and politics on gender and sexuality brought to us by radical and lesbian feminism.

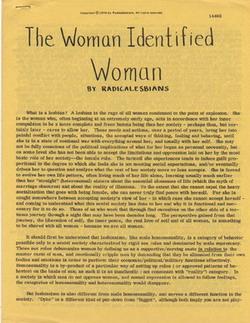

What’s exquisite in this feminism is that while centering women, it has repeatedly questioned what being a woman means in a patriarchal and heteronormative society, and envisioned future liberation from the binary system of gender and sexuality. This idea is central to “The Woman Identified Woman” manifesto by the group Radicalesbians (1970), for example.

Gender Recognition Act debates have wrongly suggested that there is a potential conflict of interests between trans and cis women. This idea often comes with a manipulative demand for “dialogue”, which offers a guise of civility. Dialogue, however, is only possible when we come from a fundamental position of unwavering solidarity and genuine care for each other’s wellbeing and when we recognize each other’s humanity without reservation and wholeheartedly. This has not been the case with these debates.

Ultimately, I support trans, as well as sex workers rights movements, because of - not despite - my radical feminism and my lesbian identity and life experience. Obviously, I am not alone. Numerous expressions of solidarity, such as the massive show-up by many cis lesbians around the hashtag #LwiththeT deliver the same message. On the policy level, we have also seen positive developments around the world. In October 2018, the Uruguay parliament passed a law on the rights of trans people, including a process for self-identification in official documents, and a pension for those who were persecuted under Uruguay’s military dictatorship decades ago. Just last month, feminist organizations working on tax justice and feminist fiscal policies, published a statement of trans solidarity (proudly endorsed by AWID, the organization where I work).

It is not surprising that the UK backlash on trans rights comes at a time of global backlash on women’s rights, which in turn is connected to intensifying fascisms and the rise of the right in many countries across the world. This is a powerful reminder for our common interest: the destruction of patriarchy, with its gender binary system and its multiple forms of violence and oppression. In the face of an alarming political context, it is up to us to create our own feminist realities, here and now. For this, we need each other. To quote Radicalesbians, “together we must find, reinforce, and validate our authentic selves”. This was true in the 1970s, and it is still true today.