Fat activism is a political field that has existed for more than 50 years in the USA and other English-speaking countries. It has links to the civil rights movements as well as to some feminist and radical lesbian expressions, amongst others. In recent years, it has started to exist in some Latin American countries.

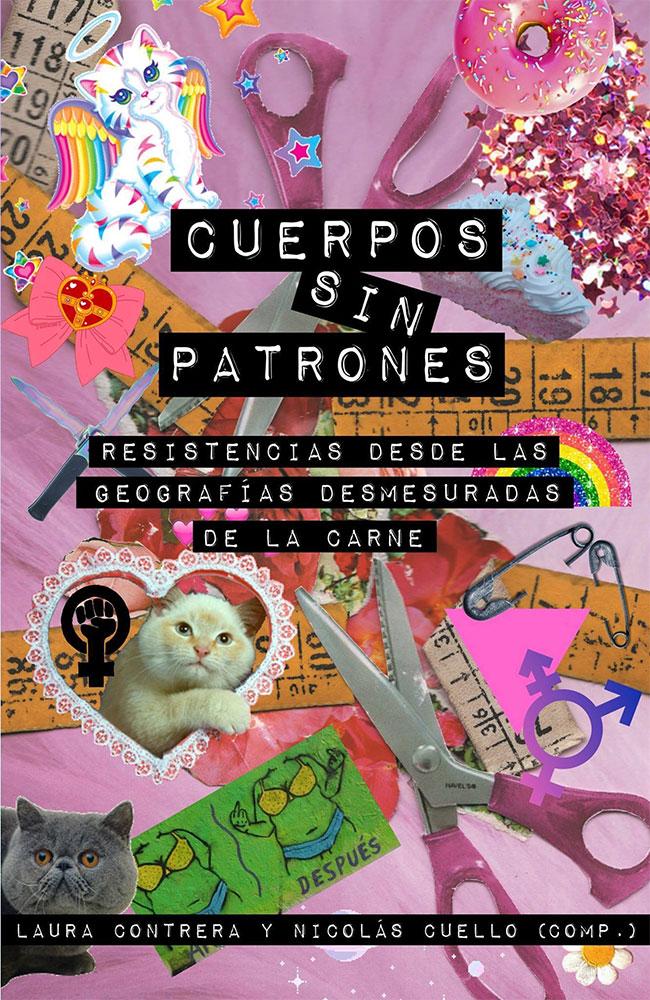

AWID spoke with Laura Contrera, bodily diversity activist, about fat activism and the book she co-authored called “Cuerpos sin patrones” [Bodies without patterns/masters].

AWID: What are the origins of fat activism and its reasons for being?

Laura Contrera (LC): Since the late 60s, activists in the English-speaking world, many of whom were feminists, radical lesbians, trans and queer, have exposed the stigmatization of fat people and how the diet industry and medical knowledge/power are complicit in spreading the notion of obesity as a social danger per se. They have also reclaimed the power of the word Fat to self- describe, transforming the insult into resistance just like other minorities have done (dykes and faggots, queer people, cripples, among others).

Even though, as Jennifer Lee says, fat activism does not necessarily solve the complex relations individuals have with their bodies, it has contributed to building a community and an alternative narrative in a society that is being bombarded by the “obesity epidemic” rhetoric, and the hatred towards unbound flesh.

This activist movement centered around fat, distances itself from the trend of feminism dealing with women’s aesthetic oppression. In the final decades of the last century, some feminists, and like-minded scholars, approached the distortion in body image that many women suffer, or their eating disorders, from the point of view of privileged female embodiments (being white, cis-, straight, able-bodied, middle class); ignoring the specific experiences of discrimination, slander and phobia those with high body weight encounter, as well as the intersections between the different axes of domination/oppression.

The book “Cuerpos sin patrones” includes the translation of a text by Charlotte Cooper where she refers to those origins and to those conflictual relationships with feminism. The book includes other articles that are seen as foundational for this movement.

AWID: How does body policing affect bodily diversity?

LC: Even though human beings come in all sizes, colors and shapes, as well as different sexual orientations and gender identities, bodies outside hegemonic norms provoke strong social anxiety. “Body policing” is the continual need to point out the failure to embody socially expected ‘norms’ in terms of weight, gender, sexual orientation, etc. This is done through insults, discrimination or well-intentioned advice.

The persistent interrogation by this un-uniformed police constitutes strong violence and stigmatization against those at the receiving end, who sometimes feel it their responsibility to avoid attacks and stigma by transforming their bodies or behaviors to fit dominant bodily patterns. This policing control also seals off the possibility of acknowledging the fascinating range of human diversity.

AWID: Who determines these dominant bodily patterns, what are they like? Where do they come from?

LC: These hegemonic patterns sprang from something we can call “bodily device”, a concept coined by scholars Flavia Costa and Pablo Rodríguez and based on the Foucaultian notion of device. There are no macabre minds behind these devices, but rather a set of practices, knowledge, institutions, laws, etc., interacting as a web; and defining what the standards of health, beauty and bodily normality are at any particular time. The lack of a deliberate plan behind the device does not mean that some actors do not benefit from body patterns and normative ideals; clearly, the medical diet industry is the greatest beneficiary of this model.

In contemporary societies under the straight-cis- capitalist system, a “healthy life” is mandatory and it comes with the mandate to take care, improve and train yourself in order to fit in with the patterns of normalcy. The goal behind this is to have an appearance that is worth being seen, praised and valued as productive and able in market terms. Even though social contempt of fat bodies, with their marks of gender, class, age, race, social status, (dis)ability, etc., is nothing new from a historical point of view. Bodily volume has been perceived as an excess (of flesh or fat) and a lack (of care or will), since the 20 th century. The same can be said about the current economic system, and this is something to think about.

Fatness, now defined as an epidemic of global scope, is a knot in which the health imperative and the body perfecting techniques such as intensive exercise, restrictive diets, aesthetic, cosmetic and surgical treatments along with other forms of body-shaping intersect. But fatness is not like any other illness: it is associated with both the excessive consumption of food, particularly of deficient types of food (a class and poverty issue), and the harmful lifestyle of those who choose sedentary lifestyles. Likewise, the presence or absence of fat places a body either on the side of those who are pathological /undesirable or of those who are normal/desirable, and this is no small thing.

AWID: How does Fat Activism challenge the pathologization of bodies?

LC: Pathologizing fat adults and children means labeling them as sick, exclusively on the basis of their body size, and of a particular weight considered to be excessive according to universal standards, which have varied throughout history for reasons that are more economic than scientific. If we look at the history of the Body Mass Index (BMI), used to determine if one is overweight or has some degree of obesity, it relates to risk-measuring charts used by insurance companies, and not to scientific data.

These diagnoses operate with the goal of perpetuating normative distinctions between how one experiences the body weight that is considered healthy, and others that are considered pathological. They force individuals to embody an ideal model, associated with a socially, more than scientifically, determined BMI, ignoring the multiple factors shaping each body and its life history. The dividing line between acceptable and pathological weight cannot be automatically applied to all individuals without taking into account these intersections.

Fat Activism considers that a person’s weight and height say little about their health condition, dietary habits or lifestyle. Only bias and hatred can read those bodies in a univocal way. Marilyn Wann, an activist from the USA, is very right in saying that by just looking at a fat person the only thing we can diagnose without fear of being mistaken is our own degree of fat-phobia.

Pathologizing all kinds of fat in itself is an obstacle to being able to overcome negative attitudes and stereotypes about fatness that are prevalent in society, as well as the multiple limitations that fat people face in all aspects of our daily life: everyday experiences of verbal or physical harassment, body-shaming (public ridicule or embarrassment based on one’s body shape), invasive comments by acquaintances and strangers on the life regime they consider suitable for us, physical and architectural barriers, difficulties in accessing employment, and lack of job opportunities, etc.

We need to be cautious, to avoid critically reproducing the naturalized association between pathologization and stigma. As activist Mauro Cabral has recently pointed out in an article written for the Argentinean newspaper supplement “Soy”, pathologizing fatness has an exacerbating effect on the stigmatization and discrimination faced by fat persons. This is expressed mainly in inequity in access to health and in difficulties in enjoying the right to health, free from discrimination and violence.

As British activist Charlotte Cooper states, forty years of fat activism have proved that there are other ways to promote health for those with high body weight, that have little or nothing to do with extreme diets or surgeries, or with degrading or shaming practices. For instance, building communities and spaces free from violence where fat persons can express ourselves through our bodies through dance, Yoga, swimming or any other sport or aesthetic discipline without fearing ridicule and harassment.

AWID: Together with Nicolás Cuello, you are the co-editor of the book “Cuerpos sin patrones”. What is it about? What discussions does it seek to provoke?

LC: Our Fat book1 came about as an exercise and commitment to affinity, based on an invitation by María Luisa Peralta from the Madreselva publishing house, to compile a few articles by activists that had been circulating on the Internet and in fanzines, like the one I have been producing since 2012, “Gorda! zine” (in Spanish).

In the introduction to the book that Nico and I wrote, we say that this compilation does not purport to be an exhaustive cartography of the landscape of local or regional Fat Activism. It is rather a geopolitically situated statement about a starting moment for a Sudaca, Latino, Punk and Deviant Fat Activism. It is a first chapter in a broader political history of bodies without patterns/masters2 . It includes a series of reflections on the impact of learning about the Fat Activism that preceded ours from different geographical and political locations; on producing Fat Activist knowledge here and now and the relationships with other gender, sexual and bodily diversity movements, etc.

We have also included translations of both, historical Fat Activist texts like the “Fat Liberation Manifesto” as well as of recent texts by activists and scholars from other parts of the world. This comes from our deep political conviction about the value of translation as an activist practice of trafficking, vandalism, appropriation and twisted re-reading of ‘other’ knowledge.

This book came out during the second semester of the conservative and anti- people government of Mauricio Macri, a cold executor of the cuts that Nicolás Cuello and I call “meagre Neoliberalism” and it is also inscribed in a global context of deepening xenophobia, hatred of migrant communities, sexual dissidents and others.

The language of the master/pattern is now the language of adjustment, debt and cuts: it cuts and trims the ‘excessive fat’, subsidies, social services; poor and ‘fatty’ bodies go into post-production, must tighten their belts and evade the eugenics while seeking to exterminate difference.

Sudaca is a pejorative word used mainly in Spain to describe South-American migrants. It has been reclaimed and used to proudly describe that identity.

1 The book has a preface written by Mauro Cabral and includes articles written by activists Lucrecia Masson, Lux Moreno, Canela Gavrila.

2 In Spanish, the author only uses the word “patrones” and plays with its two meanings (of “patterns” and “masters”).