El marco de referencia de las Realidades Feministas en el Foro se despliega a través de seis ejes temáticos. Cada uno coloca en un lugar central las realidades, experiencias y visiones feministas, dentro del continuum que va de la resistencia a las propuestas, las luchas y las alternativas.

Queremos explorar juntxs de qué están hechas nuestras realidades feministas y qué es lo que les permite florecer en las diferentes esferas de nuestras vidas. Estas realidades pueden ser formas ya muy desarrolladas de vivir, sueños e ideas que están tomando forma o experiencias y momentos valiosos.

Los ejes temáticos no son compartimentos aislados sino más bien envases que guardan las actividades a desarrollarse en el Foro y que están abiertos, comunicados entre sí. Imaginamos que muchas actividades tendrán lugar allí donde estos ejes temáticos - así como diferentes luchas, comunidades y movimientos - se entrecruzan. Las descripciones que compartimos a continuación son preliminares y continuarán enriqueciéndose a medida que continúe nuestro recorrido por las Realidades Feministas.

Recursos para comunidades, movimientos y justicia económica

Este eje temático coloca en primer plano las preguntas acerca de cómo nosotrxs - en tanto personas, comunidades y movimientos - satisfacemos nuestras necesidades básicas y garantizamos los recursos que necesitamos para vivir en plenitud, priorizando el cuidado de las personas y la naturaleza. Cuando hablamos de recursos nos referimos a los alimentos, el agua, el aire puro y también el dinero, el trabajo, la información, el conocimiento, el tiempo y otros.

Partiremos de las resistencias feministas al sistema económico dominante de explotación y extractivismo para subrayar propuestas, experiencias y prácticas feministas contundentes e inspiradoras para organizar nuestra vida económica y social. Algunas de las temáticas a explorar son la soberanía alimentaria y de las semillas, las miradas feministas acerca del trabajo y el empleo, o los sistemas justos y sostenibles de comercio. Con valentía abordaremos las contradicciones que resultan de nuestra necesidad de sobrevivir en sistemas económicos opresivos.

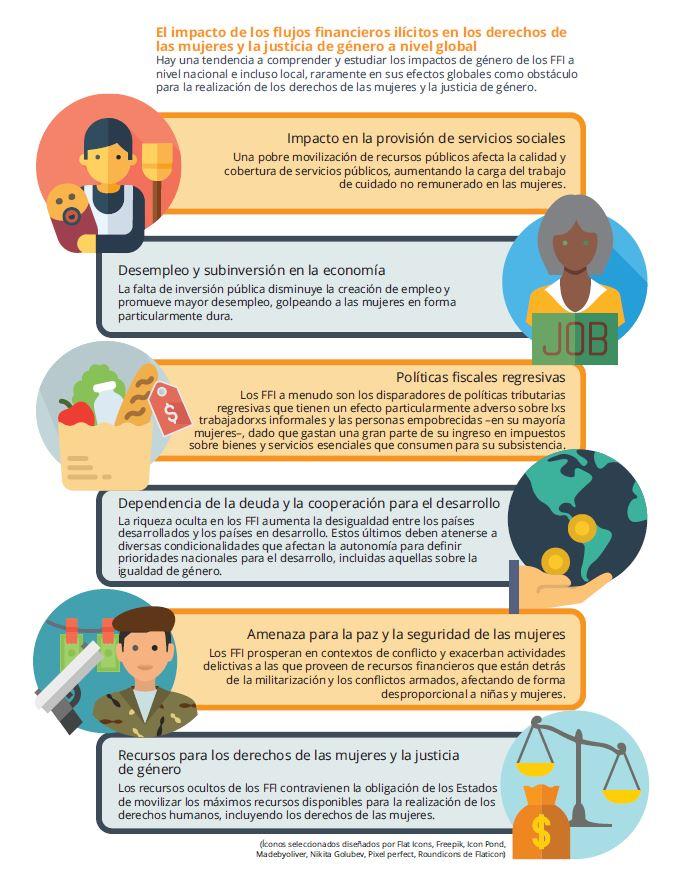

Este eje temático posiciona el financiamiento y los recursos para las organizaciones y los movimientos dentro de un análisis feminista más amplio de la justicia económica y la generación de la riqueza. Analizaremos cómo mover recursos para que lleguen adonde resultan necesarios a través de la justicia fiscal, propuestas como el ingreso universal, diferentes modelos de filantropía y la generación autónoma y creativa de recursos para los movimientos.

Gobernanza, rendición de cuentas y justicia

Queremos construir nuevas visiones y difundir las realidades y experiencias ya existentes de gobernanza, justicia y rendición de cuentas feministas. Frente a la crisis global y al auge de los fascismos y los fundamentalismos, este eje temático le da un lugar central a modelos, prácticas e ideas feministas, radicales y emancipatorias para organizar la sociedad y la vida política desde el nivel local al global.

En este eje temático exploraremos cómo es la gobernanza feminista, por ejemplo a través de experiencias de municipalismo, la construcción de identidades por fuera de las naciones-estados o nuestras miradas acerca del multilateralismo. Intercambiaremos experiencias de procesos de justicia y rendición de cuentas en nuestras comunidades, organizaciones y movimientos, que incluyen modelos de justicia restaurativa, comunitaria y transformadora que rechazan la violencia estatal y el complejo carcelario-industrial.

También le daremos protagonismo a las experiencias de desplazamiento, migración y búsqueda de refugio, así como a los procesos de organización feminista en procura de un mundo sin regímenes de fronteras letales: un mundo donde el movimiento sea libre y los recorridos posibles nos apasionen.

Realidades digitales

El rol de la tecnología en nuestras vidas es cada vez mayor y la línea entre las realidades virtuales y no virtuales se está borrando. Lxs feministas utilizamos ampliamente las tecnologías y los espacios virtuales para construir comunidades, aprender unxs de otrxs y movilizarnos para la acción. Con los espacios virtuales podemos expandir los límites de nuestro mundo físico. Pero esto tiene un costado problemático: las comunicaciones digitales son cada vez más propiedad de empresas cuya rendición de cuentas frente a lxs usuarixs es mínima. La minería de datos, la vigilancia y los quiebres en la seguridad de la información se han convertido en la norma, junto con la violencia y el acoso en línea.

En este eje exploraremos las oportunidades y desafíos feministas dentro de las realidades digitales. Estudiaremos las alternativas a las plataformas de propiedad privada que dominan el paisaje digital, así como estrategias para movernos en espacios digitales cuidando nuestro bienestar y cómo usar la tecnología para superar desafíos en términos de accesibilidad. También descubriremos el potencial de la tecnología en la esfera del placer, la confianza y los vínculos.

Cuerpos, placer y bienestar

Albergamos realidades feministas también dentro nuestro: son nuestras experiencias corporizadas. Controlar nuestro trabajo, nuestros desplazamientos, nuestra reproducción y nuestra sexualidad continúa siendo un elemento central para las estructuras patriarcales, cisheteronormativas y capitalistas. Para hacer frente a esa opresión, personas de distintos géneros, sexualidades y capacidades creamos espacios y subculturas de encuentro, de alegría, de cuidado, de placer y de profunda valoración de nosotrxs mismxs y de cada unx de lxs otrxs.

En este eje temáticos exploraremos múltiples ideas, narrativas, imaginarios y expresiones culturales de consentimiento, agencia y deseo desde las miradas de las mujeres, las personas trans, no binaries, intersex y que de distintas maneras cuestionan los mandatos de género en diversas sociedades y culturas.

Intercambiaremos experiencias sobre nuestros triunfos en cuanto a derechos y justicia reproductiva, además de desarrollar cuáles son las prácticas sociales que habilitan y respetan la autonomía, la integridad y la libertad corporales. Este eje temático vincula entre sí diferentes luchas y movimientos para que cada uno pueda incorporar las percepciones y experiencias de bienestar y placer de los otros.

El planeta y los seres vivientes

Imagínense un planeta feminista. ¿Cómo se escucha el agua? ¿Cómo huele el aire? ¿Cómo se siente la tierra al tocarla? ¿Cuál es la relación entre el planeta y sus seres vivos, incluyendo a la especie humana? Las realidades feministas son realidades de justicia ambiental y climática. Las luchas feministas, indígenas, decoloniales y ecológicas a menudo surgen de visiones y relaciones entre las personas y la naturaleza que son transformadoras.

Este eje está centrado en el bienestar de nuestro planeta y reflexiona acerca de cómo la especie humana ha interactuado con el planeta y lo ha modificado. Nos proponemos explorar aspectos de los conocimientos tradicionales y de la biodiversidad como aportes para sostener un planeta feminista y aprender acerca de prácticas e iniciativas feministas sobre decrecimiento, bienes comunes, modelos de economías alternativas/paralelas, agroecología, soberanía alimentaria y energética.

Cómo nos organizamos lxs feministas

Si bien pensamos que todos los ejes temáticos están relacionados, este es verdaderamente transversal por eso lxs invitamos a incorporar la dimensión de lo organizativo a la actividad que propongan, sin importar con qué eje/s se relaciona.

¿Cómo nos estamos organizando lxs feministas en el mundo de hoy? Esta pregunta nos lleva a prestarle atención a actores, dinámicas de poder, recursos y liderazgo; a las economías en las que estamos inmersxs; a lo que consideramos justicia y rendición de cuentas; a la era digital; a nuestras experiencias de autonomía, bienestar y cuidado colectivo. En todos los ejes temáticos esperamos crear espacios para una reflexión sincera sobre la distribución de poder y recursos y las negociaciones en torno a ellos en nuestros movimientos.

El Foro es un proceso colaborativo

El Foro es más que una reunión de cuatro días. Es una estación en un recorrido más largo para fortalecer nuestros movimientos en torno a la noción de Realidades Feministas que ya ha comenzado y que continuará más allá de las fechas del Foro.

Únete al Viaje

توفير الموارد للحركات النسوية هو أمر أساسي لتوفير حاضر أكثر سلماً وعدالة ومستقبل أكثر تحرراً.

توفير الموارد للحركات النسوية هو أمر أساسي لتوفير حاضر أكثر سلماً وعدالة ومستقبل أكثر تحرراً.