In a lecture in Argentina, Ariel Dulitzky, president of the United Nations’ Working Group on Forced or Involuntary Disappearances, said that Working Group currently has 43,000 cases of disappeared persons across the world. AWID spoke with journalist Marta Dillon[1] and popular feminist educator Claudia Korol[2] to learn more about the history of this phenomenon and how it affects women in particular.

While Adolf Hitler’s “Night and Fog” decree is considered a direct precedent of forced disappearances, this practice intensified and expanded as part of the systematic and planned repression during Latin American dictatorships from the ‘60s to the ‘80s. Today, even in countries with democratically elected governments, this form of violence has become one of the most common types of human rights violations and affects even those who are not involved in political activities.

Forced disappearances under Latin American dictatorships

After the Second World War, geopolitical tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union in what was known as the “Cold War” created a context propitious for the emergence of many of the Latin American dictatorships[3]. In 1947, the United States created the National Security Council that developed the “national security” doctrine. This doctrine, and a culture of repressing ideological dissident served as a training ground[4] for army officers from Latin American countries, in the School of the Americas in Panama.

Several of these countries took the repressive doctrine to the extreme in the anti-communist struggle in their countries. One of the modalities of violence and repression practiced by the dictatorships was forced disappearances. Genocide General Jorge Videla, chief of the military Junta that took over the Argentinean government in 1976, cynically declared during a press conference, “A disappeared person has no entity. He is not dead, nor alive, he has disappeared… There is nothing we can do about it”.[5]

As Claudia Korol explained to AWID, “Forced disappearance was the key mechanism deployed by the genocidal policies. It was a multiple crime: a living person is turned into a disappeared and the captors own their life and death. A gigantic power exerted with cruelty over those who had dared to defy power, over their relatives who, unable to mourn them, were forced to hold on to a search that involved the rest of their lives and marked them till the end, and over a society that it aimed to discipline through terror.”

In December 1992, while investigating his wife’s murder, by looking through information from the dictatorial regime of general Stroessner, Paraguayan lawyer Martín Almada found unexpected files in a police station located in Lambaré, on the outskirts of Asuncion. It contained documents that for decades had registered the history of repression in that country and in others across Latin America. The documents, later called the “Horror Archives”, started to outline the history of what was later known as Operation or Plan Condor. The documents showed how intelligence services from the United States had cooperated with their peers in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay. Operation Condor was an extermination plan targeting left-wing and social movement activists.

Mothers in protest, the start of a movement

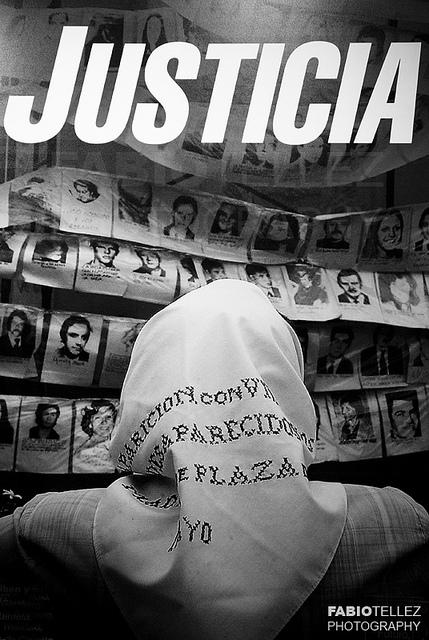

On April 30th 1977 the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, (Plaza de Mayo Mothers) began marching to the historic Mayo square on Thursdays to demand the whereabouts of their disappeared children in different government spaces. They turned the Dictator’s cynical statement around to make those who were no longer there but were being searched for, visible.

Marta Dillon explains to AWID, “We need to remember that during dictatorship and until democracy came back, the slogan was precisely “Aparición con vida” (Appearance with life). The word ‘disappeared’ was very strategic in the sense that they were not dead but alive. It was strategically deployed by the Mothers and other relatives. Particularly to say that they were not dead, they were disappeared, missing from their homes; this is what the Mothers used to say at first: ‘I am missing my son’, ‘He is missing from his home’”. This narrative of family and social existence stood as opposite to what Dillon calls the “anomie to which the military subjected women and men political activists by calling them ‘subversive’ or ‘guerrillas’”.

In December 1980, while the bloodthirsty dictatorships in Latin America prevailed, the United Nations created the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, with the mandate of assisting families in search of their missing relatives. The Madres de Plaza de Mayo, from Argentina, played a key role in creating the working group.[6]

From 1993, terrible murders and disappearances of women began in Ciudad Juarez (Mexico), the first feminicide cases known in that area. Mothers started to organize to demand justice and, for example, in 2001 "Nuestras hijas de regreso a casa" [Our daughters back home] was created. This organization is still working tirelessly along with others. When the 43 students disappeared in Ayotzinapa, Mexico on September 26, 2014, the figure of the disappeared once again took center stage, as did the broader search conducted by their relatives.

In the case of “the 43”, their mothers and fathers are using the slogan “They were taken alive, we want them alive” that mirrors the Plaza de Mayo Mothers’ claim in the 70s. State negligence and violence shows as little mercy to them as the Argentinean dictatorship did to their counterparts. As the Ayotzinapa mothers and fathers say on their Facebook page, “We demand to learn the whereabouts of our children and the police is sent against us. This is the terrible reality that we have to change.”

The recent IM-Defensoras report, highlights the many other mothers and families across the region searching and organizing, “Nuevo León or Coahuila mothers in Mexico, searching for their missing sons and daughters; the Salvadorian and Honduran women who travel migration routes searching for their missing migrant sons and daughters; the Guatemalan mothers who for decades have been searching for their sons and daughters who disappeared during the war there examples are echoed throughout all of the territories in the region”.

Disappeared women and gendered violence

Women who have been arrested and then disappeared; and those who survived imprisonment in detention camps, experienced specific forms of torture because they were women. Imprisoned political activists “suffered sexual violence, harassment, rape and in many cases, unwanted pregnancies”, explains Korol, she adds, “Disappeared women were specifically targeted for torture through sexual violence. Revealing this was taboo, because sexuality is taboo in our society. It took almost thirty years to expose it, make it visible and bring it to trial”. It was only with the Truth Trials that survivors’ testimonies were able to overcome that taboo, became embodied and acquire a voice. Survivors began to describe the horrors they and their cell companions had endured. Korol highlights that their claims, particularly those of “sexual violence as part of crimes against humanity have become essential not only to have justice done, but also to be able to think and act against one of the ways in which women historically have been held hostage, that is, the fear and shame induced in them if they say they have been raped or sexually attacked – this is a way to revictimize those who have suffered violence.”

Recently in the trial against Dictator Ríos Montt in Guatemala in 2013 for genocide and crimes against humanity, the testimonies from Ixil Indigenous women showed the abuse and violence perpetrated by military officers. According to a report by the International Federation for Human Rights, evidence was gathered about “the systematic rape of women, girls and older women, the destruction of fetuses, and also sexual slavery in the Army”. The Prosecutors submitted evidence of 1485 women raped by soldiers. Ríos Montt was found guilty but then released by the Supreme Court of his country. This arbitrary release, resulting from a legal gimmick, revictimized Ixil women.

Women disappearing in democracies

Drug trafficking, trafficking of persons, sexual slavery, and femicides multiply the ways women are being subjected to violence and disappearances, as well as the ways States repress social protest, including women human rights defenders' (WHRDs) work and activities. Neoliberal economic polices, power games with deferential gestures to corporations (particularly, to mining companies) in different countries, complicities between States and business or land owners propel some of these forms of repression.

In some instances State actors are the main perpetrators of violence against WHRDs, and many governments have reinforced the criminalization of WHRDs, “increasing stigmatization, discrediting their work, and applying the law in partisan ways to restrict rights and freedoms”. In many cases, States work to “cover up, support and encourage attacks by other actors who are increasingly involved in violence against WHRDs, such as national and transnational companies and other powerful groups like the church and organized crime”.[7]

According to IM-Defensoras report the few protection mechanisms that do exist for WHRDs do not take into account the ways in which “factors such as work environment, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or ethnic group, among others, affect the ways in which WHRDs experience human rights violations”.[8] New policies should take in account these factors, and the States should comply with their human rights obligations and guarantee the protection and the respect for WHRDs rights whatever their area of work.

*The author dedicates this article to the memory of Alicia De Cicco (1952-1975), still disappeared.