Dealing with the escalation of violence against women across the world requires a wider adoption of a feminist approach to working at the nexus of development, religious fundamentalisms and women’s rights.

In August 2015, the United Nations adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the agenda that will guide global development priorities until 2030. The agenda is not without its shortcomings, but the inclusion of a stand-alone goal to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls” and the recognition of gender equality as “a crucial contribution to progress across all the Goals and targets” constitute a significant step up from the minimal gender commitments of its predecessor, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). However, the widespread growth of religious fundamentalisms across the world stand as a huge barrier to achieving the transformation envisioned by the SDGs.

Fareeda Afridi, a Pashtun feminist and women's rights activist in Pakistan who criticised patriarchy and the Taliban, was shot dead on her way to work in July 2012, at the age of 25. Talata Mallam was one of nine women polio vaccinators shot and killed in attacks in Kano, Nigeria in February 2013. In November 2015, Jennifer Markovsky, Garrett Swasey, and Ke'Arre Stewart were killed by a Christian extremist at a Planned Parent Federation Clinic in Colorado Springs, USA. Attacks by fundamentalists in Bangladesh on NGOs like BRAC and the Grameen Bank, which provide health, information, education services and economic opportunities particularly to rural women, have included beating and killing NGO workers and burning hospitals. These are just a few examples of the thousands of attacks by religious fundamentalists of all persuasions on women’s rights and development work.

Religious fundamentalisms degrade human rights standards, roll back women’s rights, entrench discrimination, and increase violence and insecurity. However, fundamentalists do not only use physical force. Fundamentalist forces are selectively using human rights language, with culturally relativist arguments, to attack existing international human rights standards, and block progress. Yet, so far, little work has been done to address the specific challenge of religious fundamentalisms to development or to formulate effective responses.

A worldwide problem for women’s rights

The control of women’s bodily autonomy and the policing of strict gender norms is a hallmark of fundamentalist ideology that transcends all religious and geographical boundaries.

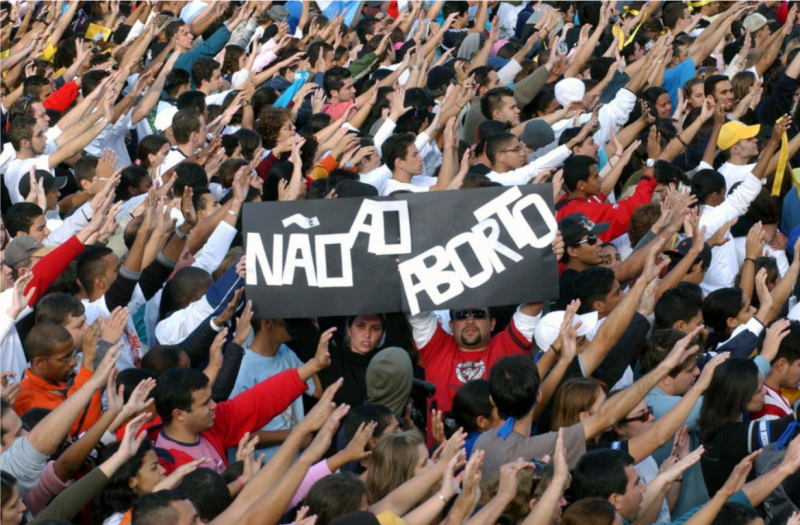

And things are getting worse. In 2014, Brunei introduced a new Penal Code based on an extremely conservative interpretation of Muslim laws, which included death by stoning as a punishment for adultery. In the United States, the strengthening of the Christian right led to the enactment of more than 288 measures impeding access to abortion between 2010 and 2016. From Poland to Brazil, recent months have seen the religious right pushing countries closer to all-out bans on abortion.

In Burma and India, fundamentalists use gender as a central mobilizing tool in anti-Muslim hate campaigns; stereotypes about Muslim men coercing women to convert to Islam and rumours about Muslim men raping Buddhist or Hindu women are used as a basis for restricting women’s choice of partner and to provoke anti-Muslim violence.

From the terrifying rise of Da’esh in the Middle East, to the “army” formed by the evangelical Universal Church of the Kingdom of God in Brazil, and the 2,500 attacks on abortion providers in the USA between 2005 and 2013, non-state actors pose violent threats to women’s freedoms and lives.

The violence fundamentalists are wreaking on women’s lives may manifest in different ways in different contexts, but it is clear that we are currently witnessing an escalation across the world.

The development sector’s capacity to respond

Faced with this situation, the promises to “leave no one behind” from the development agenda feel rather far from reach. Some development organizations are only starting to grapple with fundamentalisms’ implications for sustainable development and their strategic approach to the issue. Others have policies and internal capacity-building programmes designed to ensure staff are aware of “gender and diversity” issues. These can offer some space for discussions that touch on religious fundamentalisms. However, discussions of diversity tend to remain superficial and often do not examine the politicization of identities, and are devoid of a strong power analysis. Instead, they simply reinforce the notions that “we are diverse, and must all respect one another”. Meanwhile, fundamentalists often manipulate ideas of diversity for their own gain, shutting down criticism of their brand of women’s oppression with complaints of cultural insensitivity.

Development policy-makers’ reluctance to engage in discussions on the ways religion is being used to justify discrimination and violence, may be because religion overall is seen by many as simply too sensitive. There may be a general “risk averse” culture within some organizations, which limits willingness to take on such challenges. Moreover, they may also feel that this area is best left to others, and there may be a fear of getting in above their heads or offending local staff and beneficiaries. Development organizations must develop a collective capacity to recognize and collaboratively address religious fundamentalisms if they are to advance social, economic, and gender justice and the human rights of all people in sustainable development.

A feminist approach

What is needed is something that goes deeper - assessing the root causes and power relations that underlie the rise of religious fundamentalisms. Feminist organizations have been at the forefront of documenting and analysing the problem, and building strategies for resistance. A wider adoption of a feminist approach is crucial for working at the nexus of development, religious fundamentalisms, and women’s rights. A feminist analysis reveals women’s bodies to be a site of control for religious fundamentalists and allows one to see gender-based violence across social levels - from the state down to the family. It is also vital for imagining ways of combatting fundamentalisms that do not create further conflict, inequality, or oppression. What this looks like in practice, however, can be hard to figure out. The latest research from the Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) suggests some concrete actions that can be taken in seven main areas in order to resist fundamentalisms and strengthen women’s rights.

Act on the warning signs

Religious fundamentalisms do not spring up “fully grown”. Generally, there is a gradual process, beginning with control over women’s bodies - the way they dress, their presence in public space, their sexual and reproductive autonomy - along with the policing of a strict gender binary and gender roles, the valorization of a patriarchal family form, and the imposition of heterosexual “normalcy”.

Often, and especially in times conflict, insecurity, or political upheaval, women’s and LGBTQI people’s decreasing freedoms are dismissed as unimportant or “not the main issue”. To combat the rise of religious fundamentalisms it is vital that development actors take action when these groups raise the alarm, and that they do not wait for fundamentalisms to grow stronger and more embedded in society before considering them a serious problem.

Do away with homogenising identities

There is often a temptation to assume that religion is the primary identity marker of a community. However, in reality people’s identities are made up of many facets. Reducing a community to a single identity based on religion essentializes that community and the individuals who constitute it, in a similar way to fundamentalists. Furthermore, religious discourses are often used to protect power and privilege, so allowing an issue to be framed in religious terms alone can risk not only conceding the terms of debate, but also missing the chance to effect change.

It is important that development actors do not assume that a conservative religious discourse is the only one that a community can relate to. Instead of the bounded, othering identities fostered by fundamentalists, development actors can help promote positive inclusive forms of identity. Development interventions can use non-religious language that speaks to common goals such as peace, justice, rights, quality of life, an end to violence, access to water, or better health, for example. Combining arguments from multiple sources - human rights and gender equality, constitutional law, progressive religious interpretations, empirical data - can be very effective.

Promote a feminist understanding of religion, culture, and tradition

Religious fundamentalists tend to claim that they are guardians of “authentic culture” and are resisting domination by “foreign” or “western” powers. However, in reality fundamentalists often introduce norms that not only destroy cultural diversity and pluralism, but which are also often neither “authentic” nor local; being modern ideologies or imported from other contexts. The myth of a single “Islamic law”, for example, has long obscured the actual diversity of Muslim laws and practices and their intersection with culture and history across the world. Appeals to notions of “African culture” in anti-homosexuality discourse obscure the reality of diverse sexualities in Africa historically and that growing anti-gay sentiment in many African countries is fuelled and funded by Christian fundamentalists from the USA.

Sometimes development initiatives appear to accept the culturally relativist arguments that curtail women’s rights, either out of a pragmatic desire to enable a project to move ahead, or out of fear of being seen as interfering in a sensitive topic. However, it is important that religion culture, or tradition is never accepted an excuse for human rights violations or the subordination of women, and that religious leaders are not assumed to represent an entire community.

A positive way forward would be for development organizations to ensure that all staff are sensitized to understand that religious discourses, like all discourses, are not static, but are continually contested, reinforced, and altered. Furthermore, development actors can have a positive impact by supporting the local actors, often women’s organisations, who are enabling people to discuss religious discourses that are congruent with human rights and gender justice.

Address marginalization, including racism

Fundamentalist groups capitalize on the grievances of those who feel marginalized, or who have little hope of gaining social and economic power, or being represented through democratic political means. The numbers of middle-class Western recruits to Da’esh speaks to the racism and alienation experienced in Europe and North America by non-white youths. In many countries “progressives” (leftists, pro-poor, anti-imperialists) have been unable to muster sufficient support to pose a credible alternative to elites in power. As a solution to marginalization and disaffection, fundamentalisms offer their followers hope, certainty, a sense of purpose and an emotional community. In some countries, Poland and Egypt for example, religious organizations have historically been persecuted as dissidents, which has given them credibility as alternatives to corrupt regimes.

It is therefore important that opposition to fundamentalism does not take forms that reinforce racist and other marginalising discourses. It is also important that development interventions work concomitantly on the politics of inclusion and representative, responsive governance, the rule of law, and against corruption. Programmes should cultivate the values of and skills for peaceful negotiation and dialogue, not only for marginalized groups but also for those with power, to ensure that the various levels of governance and administration are responsive to dialogue.

Address structural inequality

As much as religious fundamentalisms relate to ideas about culture, identity, and tradition, the reality is that fundamentalist movements are also intrinsically linked to structural inequalities. Neoliberal economic policies have produced inequality, which has fed the power of fundamentalisms. The destruction of states’ responsibility for social welfare has provided fertile ground for the ascent of conservative religious actors. Where states have ceased to provide services such as healthcare and schooling, fundamentalists have stepped into the breach, reaping rewards in the form of loyalty of the populations they serve and access to new channels to spread ideology.

It is therefore necessary that development organizations do not support programs that minimize state responsibility for providing services and social safety nets. They should add their voices to the calls for alternative economic models that focus on redistribution, state provision of services, and that place women’s rights and justice at the center of their policies. It is also vital that they take a role in holding states, financial institutions, and corporations accountable for the effects of their policies on human rights and gender justice.

Make the right partnerships

There is often a belief that religious organizations should be chosen for development partnerships, based on assumptions that they have better access to the population, and respect amongst the community; and also as a response to a lack of state institutions to work with. Not only can such assumptions can be unfounded, but it must be recognised that partnering with any organization builds their legitimacy and access to resources, and supports their ideology, including gender ideology. A desire for short-term efficacy has in some cases led to negative effects in the long-term.

In the aftermath of Pakistan’s 2005 earthquake and 2010 floods, humanitarian partnerships led to the strengthening of Islamist groups, for example. There were documented reports of INGOs and the UN establishing working relationships with Islamist groups - even those linked to terrorist activities in Pakistan in 2005 - and channelling aid and relief through their networks. Similarly, religious groups involved in development interventions to stop the spread of HIV/AIDS have been known to “moralize” messages around sexuality and gender, causing further stigmatization of sex workers, drug users, and LGBTQI persons, while leaving the structural drivers of the epidemic untouched.

It is important that development organizations do not choose partners based solely on short-term goals, but prioritise long-term objectives of sustainable development and gender equality. Prioritizing progressive positions on human rights, women’s rights, and gender equality when choosing partners for development initiatives is a key step in channelling resources and legitimacy away from religious fundamentalists.

Support women’s movements

Women’s rights organizations have long been active in challenging religious fundamentalisms. They already have the knowledge and strategies they need - but the missing factor tends to be financial backing. Women’s rights organizations remain massively under-resourced in absolute terms and by comparison to other types of NGOs, often having access only to project funding for direct service provision. Whilst new actors deploying resources have entered the field over the last five years or so, much of those new resources are directed to individual women and girls, thus “watering the leaves and starving the roots”, as described by a 2013 report from AWID.

It is important that development organizations are able to look beyond the usual mainstream groups and pursue partnerships with the in-region or in-country actors, and women’s organizations in particular, who are already working to resist fundamentalisms. It is vital that donors direct resources towards women’s rights organizations that build and support autonomous women’s movements. Given the length of time this takes, this means providing multi-year and core funding. We have recently seen moves by some donor organizations towards this approach, which is a step in the right direction.

There is now strong evidence that the single most important factor in promoting women’s rights and gender equality is an autonomous women’s movement. Srilatha Batliwala, has noted the “significant amount of evidence…demonstrating how organizations with a strong focus on women’s rights and gender equality can “move mountains” in a relatively short space of time” when they are adequately resourced over a reasonable period of time, and supported to use the strategies they have crafted rather than donor-driven approaches. Women’s rights groups have the know-how to resist fundamentalisms and - when adequately supported and resourced - hold the key to weeding out religious fundamentalisms, whilst cultivating social and equality and gender justice.

This article was originally written and published for Open Democracy