Written and interviewed by Tenzin Dolker

Edited by Muna Gurung

Illustrations by Priyanka Singh Maharjan

Introduction

Over the last few years I spoke to a number of incredible feminist activists from different parts of the world. Sharing deep insights about the past and present state of feminist organising and resourcing, they reflected on the complex, multi-sourced, and often invisible ways that movements resource their work. We discussed forms of resourcing that are autonomous or outside philanthropic and governmental models, which we have been calling, “autonomous resourcing.” We also discussed the range of strategies and priorities activists and movements identify for resourcing feminist social change.

Launching the first of a series of interviews, I spoke to Chayanika Shah, a feminist and queer rights activist who has had a long history of co-building autonomous feminist movements in India. At the center of their feminist organising has been their fight for “autonomy”, in every sense of the word. Organising in the years following a dark period in India called “the emergency” of the 1975-1977, Chayanika reflects: “The autonomy was defined in terms of autonomy from political parties, autonomy from funding, autonomy from the state, and autonomy to an extent from men. That's the nature of autonomy that we were talking about, and we were very conscious of that fact.”

Below is our conversation edited for length and clarity.

Tenzin Dolker:

Can you share a little bit about yourself and your feminist journey?

Chayanika Shah:

I have primarily been part of urban, autonomous collectives in the city of Bombay. One of them is the Forum Against Oppression of Women (The Forum), which was founded in 1979, and the other was LABIA, a queer feminist LBT collective, which was formed in 1995. Both collectives have chosen to remain non-registered, which means we haven’t put ourselves on the state's records anywhere.

The Forum has been around for over 40 years, and we’ve met at least once every week. We started as a forum against rape, but over the span of four decades, we’ve tackled issues ranging from rape to domestic violence, to personal laws, to family laws, to health issues, communalism and many others. Of late, we have found ourselves addressing civil rights and liberties issues because of the kind of climate in which we are living today in India.

TD:

In all the years of feminist organising, how have you worked around funding?

CS:

In the last 40 years, there has only been one time that the Forum has taken indirect funding. It was while conducting surveys and research to supplement the work of the Sachar Commission, set up to understand the socioeconomic situation of Muslim communities in India. We were specifically focusing on the plight of Muslim women and inquiring about what the state can do to implement the recommendations of the commission.

TD:

Otherwise members were volunteering?

CS:

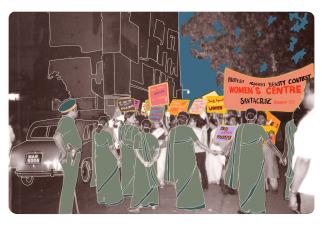

Essentially. In 1980, when we started addressing cases of domestic violence, there were no laws or mechanisms around these issues, so we had to create our methods as we went along. Someone would approach us with her problem at home, we would give her shelter, counsel her, and even fight against her family. We were doing all the things that are required by law today but were unavailable then. But what we understood at that point was that we could not sustain our work by simply volunteering. That is when we decided to set up The Women’s Center, which in our imagination in 1982, was going to be a funded service providing organisation with full-time staff. The Forum, on the other hand, would remain voluntary and non-funded or non-registered, but Forum members could volunteer at the Center, thus maintaining a synergy between the two.

But that only lasted from 1982 to 1985. There were problems on both sides around accountability, decision-making, and collective functioning. It was clear that the people who worked in the organization full-time felt like they were being loaded with all the responsibilities while the volunteers were free to go in and out in their own time. Some of the people who volunteered felt that the same structures and hierarchies that they were defying were being replicated at the Center. Many issues came up in 1985, after which, many of us from the Forum stopped volunteering at the Center. Most of the Center's members were part of the Forum’s and vice-versa, but now people had to choose sides and decide where they stood. Eventually the Forum and the Center started operating as two independent organisations. But this is not an uncommon story in India or elsewhere.

TD:

Can you share a bit more about the collective's intentions and decisions around taking or not taking funding?

CS:

This strand of the women's movements in its initial years was made up of people who mainly came from the political left, where they felt like they were not being heard. And this was true beyond Bombay; in Delhi, Calcutta, Chennai, Hyderabad and other big Indian cities, a similar story was unfolding. We understood that we had to be autonomous, and that autonomy was defined in terms of autonomy from political parties, autonomy from funding, autonomy from the state and autonomy to an extent from men. That's the nature of autonomy that we were talking about, and we were very conscious of that fact.

From 1975 to 1977, India had seen a very repressive regime of the “Emergency years”. We were organizing right after the Emergency had ended, so we were standing in a moment when we recognized the state and its power. Hence, we made clear choices about not wanting to be under the state’s radar.

In those years, foreign money didn’t come into the country as easily, at least not for social movements. So for the Center we did a lot of fundraising through charity shows, film screenings, collecting individual donations from people across the city. Eventually it created a corpus enough to buy a flat in Bombay, and that’s large money, since property is always expensive in Bombay. The day-to-day running cost of the organisation and what little money the permanent staff took, that money came from funders.

TD:

Who were these “funders” for the Center?

CS:

The Center was funded by small American donors with feminist understanding. We were very conscious of who we were taking money from. It’s interesting that the ongoing debate in the women's movements around funding makes it seem like there are two warring sides: the anti-funding side versus the pro-funding side. But most of the time, we managed to talk across the divide, and we often realised that for some work we need funded organizations. The presence of non-funded collectives also helps to keep this tension alive. Out of the non-funded collectives that began in 1980, there are only two surviving today. One is the Forum and the other is Saheli in Delhi. The rest either stopped operating or broke into smaller organisations.

TD:

And the Women's Center in Mumbai in the old flat is still functioning, correct?

CS:

In the last 10 years, the funding for the Center dried up but there is one person who still keeps the flat running. In a strange turn of events, the Forum meetings are happening back at the Center again. We’ve made one circle back to where we started. But the flat is the Center’s and doesn’t belong to the Forum. We have been meeting in peoples’ homes and public spaces all these years, so now this flat is just another venue for us. As for the tension, there is more equanimity and a sense of having to work together that has evolved over the years.

TD:

Say more. How did the community and that energy evolve?

CS:

The distinction that the Center was primarily doing service provision work for domestic violence survivors, and that the Forum was doing more campaign-related work remained. Over the years, more and more organizations started their own counseling or drop-in centers, so by the mid-80s, the Center was not the only space of such kind. Later, there were other kinds of campaigns around laws related to domestic violence or personal laws that took off where we overlapped. So the Forum was involved in those campaigns, but in terms of actually reaching out to women in situations of domestic violence, we found that the more difficult cases - or whatever was deemed difficult at that time- came to the Forum.

I remember sometime in the late 80s, there was a divorcee who had fallen in love with a married man at her workplace, and as a consequence she had lost her job. That case came to the Forum. Then later in the 90s, there were two women who were in love with each other but one of their mothers had threatened them with police action. So they came to the Forum. It was, you know, cases that people felt like other organizations would either be moralistic about, or would not take up because those organizations had become more like mainstream NGOs.

TD:

So does the autonomous setup enable you in any way to do what you wouldn't have otherwise done had you been taking traditional forms of funding?

CS:

There’s a lot of give and take. From what I have seen, as far as working in the field of domestic violence goes, most funded organizations are unable to take a radical stand because of their funding status. But I don’t want to overlook the kinds of interactions that have taken place across organizations, or that have allowed for innovative shifts to take place.

This is where the story of LABIA comes in. When LABIA was formed, we decided to remain unregistered again, and it was a debate that we revisited regularly at LABIA. There are already so many organisations working around domestic violence, we felt that as LABIA, our work was actually to equip those organizations to take on cases of lesbian women and trans people in particular – basically cases that came to us but perhaps cases that needed more support in terms of interaction with the state, or the police.

TD:

It seems like you were clear about not wanting to set up another NGO.

CS:

In today's political climate in India, no right-minded person would want to register with the state. The kind of repression that everybody in the last decade has had to face has been unparalleled in our history. Have you seen the way people who raise their voices or assert any kind of dissent are being treated?

TD:

Yes, there’s a lot more surveillance and scrutiny.

CS:

The fear around why we began organizing autonomously in the 80s is being realized today. People are being caught because their finances are being looked at; if one bill here or there is mislaid, their foreign funds are stopped or their registrations are taken away. Also, the state either keeps changing or adding new rules, so to keep up with their conditions in order to simply run an institution is a full-time job.

TD:

I understand that both the Forum and LABIA members are largely self-funded. Can you tell us about how you resource your organizing autonomously?

CS:

At LABIA, the principle has been to raise small funds as and when needed from those who are financially better off within the queer community. Over the 24 years when I was active in LABIA, we consistently encountered couples who had run away from home. And that kind of work is resource intensive because if people are coming to you, then you have to make sure you know where they will stay, how they will survive, how to give them access to education, or some skill-building training so that they can get on with their lives.

For fundraising, we’ve done things like throw parties, which queer people are really good at! And at these parties, we organized creative games and activities to bring in even more money. The money raised at these events would be used for the specific cause it was raised for, and then the rest would be put aside as "crisis fund". In addition to raising funds for couples, we have also raised money for education and each one of us at LABIA also contributes from time to time. Apart from asking from the larger community who are not part of LABIA, there are other queer people around us, and so we tap into that network and try and generate as much as we can. We’ve also fundraised for people to travel. People are scattered across the state and in the interior parts of the country; there are many who have been in touch with us over the phone, but who we haven’t met. They tell us that they are very isolated where they are. It is true for everyone, but especially for queer folk, it is important to get them to meet others like them. For all these kinds of expenses we've fundraised on our own. The money we took formally as LABIA was in 2009 for a research study where we travelled across the country to collect queer narratives.

TD:

Can you tell us more?

CS:

It came to us as a project through another funded organisation who housed it. It was a large study, and in the first year, eleven of us worked together on it. Later, four of us who were part of the research team took time off to finish writing and brought out a book, No Outlaws in the Gender Galaxy.

TD:

What is the financial state of the two organisations these days?

CS:

Over the years, we've realized that it is not that we haven’t been able to do things because we don't have the money, it is because we don't have the time. The people who are in these organizations want to keep their other lives going. I have been a physics teacher for the longest time, and many of the members of the Forum had their own earnings from elsewhere. For regular expenses, the Forum collects Rs.50 a month from its members; with 15 of us that is Rs. 750 a month, which is nothing actually, but then again what are the expenses? But it is extremely difficult for the younger generation today because expenses in the city are increasing and voluntary work is becoming unsustainable.

TD:

The Rs. 50 from a membership model that you have at the Forum is really significant and symbolic in connecting to what you're saying about how it's not about the money. But at the same time, how do you push for change when you’re simply trying to survive within this privatized neoliberal capitalist socioeconomic context?

CS:

This speaks to the nature of the collectives. Both these collectives have members who are autonomous, middle class urban people who have money of their own to spend. So we don’t have people who are already burdened with economic or other responsibilities. I mean, the organisation’s class is very evident. No voluntary functioning happens without this kind of class privilege that many of us have. Very often caste privilege also goes along with class privilege. So, groups become very homogenous and belong to a minority that does not represent or reflect the larger populations around us.

TD:

What are the ways in which you think the current resourcing ecosystem could be transformed, so that indeed, funds reach feminist movements in a way that they need to?

CS:

The problem is not so much with the funders as it is with the watchfulness of the state. So this is an internal issue and organizations have to be smarter. Both the Forum and LABIA have people that are part of funded organizations and we do this dual thing where the other funded organization's name does not appear in any anti-state actions, but the collectives’ names are used instead.

One problem is that funders don’t like to give small money. The HIV/AIDS money that came into the country, which was big money, was routed through four large NGOs. These NGOs then built smaller community organizations and became the conduit for transferring money to those organisations. The other thing that funders do is come up with specific agendas for their money, so they will say, "Okay, now, the flavor of the year is adolescence." And then everyone scrambles to make something work within those parameters. This does not allow the sustaining of long term agendas as movements.

One good thing is that people are raising funds domestically. Internal domestic funding can help shut off state repression. But the problem is that most of the money in the country is for explicit charity, like building temples, hospitals and schools, and very little for social justice work. The other positive thing is that people are working as much as possible with the state for service provisions. For domestic violence for example, organizations are not going to be around forever, so we have to work towards putting in state mechanisms. In the last forty years, we’ve put a system in place, so now a lot of organizations are working towards making sure that the people who have been hired are well-trained, that materials are created, workshops are held, and so on and so forth.

TD:

Is that something autonomous movements or collectives are all engaged in?

CS:

The organisations in service provision are nodal agencies who work with the state. So a group like Forum is slightly removed. We understand the broad framework of a law, and we work in the campaigning for that law to be instituted, but the actual day-to-day functioning of that law is still done by organizations that are looking at these issues as service. Many of them are active and specialized.

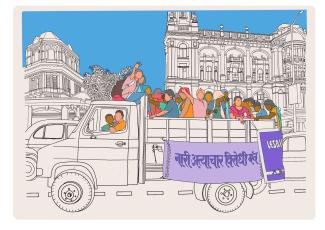

It is exciting that new autonomous movements and collectives have come up in the last decade such as the Women Against Sexual Violence and State Repression (WSS), which is a nation-wide network of women from diverse political and social backgrounds, and Feminists in Resistance, which is a Calcutta based collective. These collectives, and many others like them, are taking on the state more openly and amplifying feminist voices, and their need is recognized and felt especially as state repression in India grows.