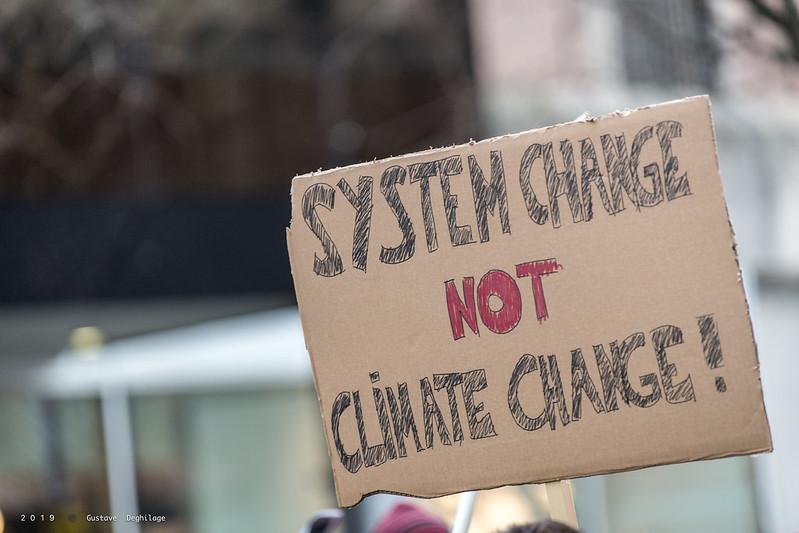

Last week, over 4 million people across 185 countries participated in the biggest human climate protest in history. With girls and young people at the forefront, the protests were the result of decades of mounting, tangible evidence of environmental collapse, strong scientific research and longstanding grassroots movement-building for just and sustainable alternatives by frontline communities.

Within the global South and the colonized, racially and economically stratified North, women, LGBTIQ and other marginalized communities are the first to suffer and die in increasingly common climate-related catastrophe. Climate change places women and girls at a heightened risk of harm, from unequal access to health care and resources to a higher risk of sexual violence, sexual exploitation and abuse, trafficking, and domestic violence.

LGBTQ people already face disproportionate exclusion and violence in most parts of the world, often having to flee their homes due to family conflict or rejection. In places where homeless shelters exist, LGBTQ people face the extra danger of homophobic and transphobic violence, which support workers are often not equipped to handle, and which pushes them more to the streets. In the context of a climate disaster, where housing is often the first and most primary site of loss, this creates an existential threat on a different scale for people and communities whose survival is already precarious.

And yet Indigenous, formerly enslaved, and anti-colonial movements have been resisting and building alternatives for hundreds of years. Imeh Ekemini and Abeni Asantewaa, organizers with Berlin’s Black/People of Colour Environmental and Climate Justice Collective pointed out that the climate crisis has long been a reality for many people and ecosystems in the global South. In the present, it is the destruction caused by cyclones in Mozambique and Zimbabwe, continuing forest fires in the Amazon and Angola. But the centuries-long war economies and forced resource extraction for profit that has led to our current climate crisis were enabled by enslavement and colonization.

Visit No Borders Media's Facebook page

Likewise - Ekemini and Asantewaa remind us - anti-colonial resistance has long been interwoven with environmental protection. Indigenous, Black, global South and racialized communities have continuously fought for land rights against large-scale deforestation and resource overexploitation with ancestral and innovative knowledge and practice.

And women and LGBTQI people have always been at the forefront. Take sisters Kanahus Manuel and Mahuk Manuel of the Secwepemc Women Warriors, on the frontlines of resisting a crude oil pipeline expansion on unceded Secwepemc territory in the northern part of Turtle Island. Part of an Indigenous community of preservation and resistance, the sisters live the connection between land, food, human rights, traditional birthing practices, and the right to self-determination of their people. “It’s not just stopping a pipeline,” says Kanahus. “It’s protecting our land, our territory.”

These connections are equally evident across the ocean. In South Africa, Margaret Mapondera from WoMin, an African gender and extractives alliance which works with women, mining-impacted communities and peasants, points out the links between recent xenophobic attacks in South Africa and the climate crisis. "We can’t talk about xenophobia in the South African context (or anywhere) without talking about the climate crisis – catastrophes such as Cyclones Idai and Kenneth which hit parts of southern Africa hard earlier this year, ongoing and worsening droughts, depleting biodiversity and water scarcity – and the direct and indirect costs and violence that women are bearing because of the situation,” says Mapondera.

“We can’t talk about any of these without understanding that the climate crisis is caused and exacerbated by a capitalist model of development that prioritises profit (the unchecked extraction and exploitation of mineral wealth, and the burning of fossil fuels) at the expense of people and the planet.”

In Chennai, India, organizers with the “Save Chennai Wetlands” climate strike, warn that climate change-induced sea level rise is threatening the livelihoods of small-scale, artisanal fishing communities. “The fisheries economy is dependent on the women of the community, who play a vital role in markets and trade, value addition and ensuring food security for families,” says organizer Pooja Kumar. “Collapse of coastal wetland ecosystems due to climate change impacts will result in livelihood loss and create adverse impacts on food security.”

Amparo Miciano, Secretary General of the National Coalition of Rural Women of the Philippines and convenor of Women in Emergencies Network, adds that the climate emergency will intensify existing dangers faced by the most vulnerable women.

“Rural women - women farmers, fishers, indigenous women and agricultural workers experience impacts of climate change differently because of existing historical and structural unequal power relations between men and women. Women, especially in rural communities in the Philippines experience and feel the impacts of climate change and they act on them in different ways. They need to be heard. If we demand climate justice, there should also be gender justice.”

For Ekemini and Asantewaa, the call is urgent, and the message is clear:

“We need an intersectional climate movement and climate policy including decolonial, queer feminist and ecological perspectives.”

“We demand the end of this exploitative way of life at the expense of ecosystems and people in the global South. We demand the recognition of the responsibility for the historical greenhouse gas emissions and their consequences. We demand recognition of climate change as a reason for flight.”

During the September 2019 global climate strike, the profound urgency to our collective survival could not have been clearer. Let us not lose that sense of urgency. Let us deepen our understanding of how this struggle is connected and embedded within existing movements for survival and justice. Let us strengthen those connections, and in the face of this existential threat, let us renew our commitment to building just, anti-colonial, feminist alternatives.