Yusdiana

WHRDs are self-identified women and lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LBTQI) people and others who defend rights and are subject to gender-specific risks and threats due to their human rights work and/or as a direct consequence of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

WHRDs are subject to systematic violence and discrimination due to their identities and unyielding struggles for rights, equality and justice.

The WHRD Program collaborates with international and regional partners as well as the AWID membership to raise awareness about these risks and threats, advocate for feminist and holistic measures of protection and safety, and actively promote a culture of self-care and collective well being in our movements.

WHRDs are exposed to the same types of risks that all other defenders who defend human rights, communities, and the environment face. However, they are also exposed to gender-based violence and gender-specific risks because they challenge existing gender norms within their communities and societies.

We work collaboratively with international and regional networks and our membership

We aim to contribute to a safer world for WHRDs, their families and communities. We believe that action for rights and justice should not put WHRDs at risk; it should be appreciated and celebrated.

Promoting collaboration and coordination among human rights and women’s rights organizations at the international level to strengthen responses concerning safety and wellbeing of WHRDs.

Supporting regional networks of WHRDs and their organizations, such as the Mesoamerican Initiative for WHRDs and the WHRD Middle East and North Africa Coalition, in promoting and strengthening collective action for protection - emphasizing the establishment of solidarity and protection networks, the promotion of self-care, and advocacy and mobilization for the safety of WHRDs;

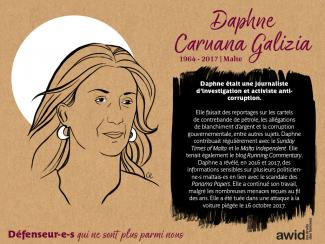

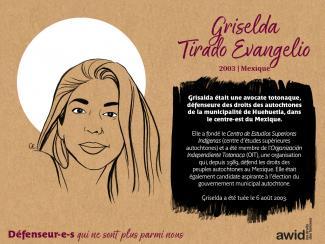

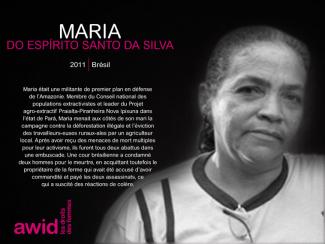

Increasing the visibility and recognition of WHRDs and their struggles, as well as the risks that they encounter by documenting the attacks that they face, and researching, producing, and disseminating information on their struggles, strategies, and challenges:

Mobilizing urgent responses of international solidarity for WHRDs at risk through our international and regional networks, and our active membership.

("exchange hand")

Term of the black communities of the Northern Cauca for the minga, the collective work based on solidarity and mutual support.

Les Femmes Maintiennent les Soins | Les Soins Soutiennent la Vie | La Vie Soutient l'Économie | Qui s'Occupe des Femmes ? | Pas Une de Moins1 | Ensemble | Déjeuner du Dimanche

1Nenhuna a menos se traduit littéralement par « pas une femme de moins » ou « ni una menos » en espagnol - un célèbre slogan féministe en Amérique latine qui a émergé en Argentine en réponse à l'augmentation de la violence sexiste.

![]()

La encuesta está disponible en árabe, español, francés, inglés, portugués y ruso.

L’enquête WITM mondiale est un des piliers essentiels de la troisième édition de notre recherche orientée sur l’action, intitulée Où est l’argent pour l’organisation des mouvements féministes? (abrégé en Où est l’argent ou WITM, pour l’acronyme en anglais). Les résultats de l’enquête seront développés et approfondis à l’occasion de conversations profondes avec des activistes et des financeurs, et les références seront croisées avec d’autres analyses et études existantes sur la situation du financement des mouvements féministes et de l’égalité des genres à travers le monde.

Le rapport complet de la recherche Où est l’argent pour l’organisation des mouvements féministes sera publié en 2026.

Pour en apprendre davantage sur la manière dont l’AWID met en lumière l’argent utilisé pour et contre les mouvements féministes, consultez notre dossier WITM et nos précédents rapports à ce sujet ici.

Pour en apprendre davantage sur la manière dont l’AWID met en lumière l’argent utilisé pour et contre les mouvements féministes, consultez notre dossier WITM et nos précédents rapports à ce sujet ici.

Este informe recuerda y celebra el primer año del nuevo plan estratégico de AWID, cuando dimos nuestros primeros pasos hacia los resultados deseados: el apoyo a los movimientos feministas para que prosperen, la impugnación de las agendas antiderechos, y la creación conjunta de realidades feministas.

Trabajamos con feministas para desestabilizar las agendas antiderechos, y logramos importantes victorias, peleadas y ganadas dentro del sistema de Naciones Unidas, cuando se logró la inclusión de lenguaje innovador sobre discriminación estructural, derechos sexuales y obligaciones de los Estados en una cantidad de resoluciones. Sí, el sistema multilateral está en crisis y necesita un sólido fortalecimiento, pero estas victorias son importantes, ya que contribuyen a la legitimidad de las demandas feministas, brindando a los movimientos feministas más puntos de presión y más impulso para promover nuestras agendas.

Ensayamos y pusimos a prueba distintas formas de construir conocimientos con los movimientos feministas a través de seminarios en línea, podcasts y conversaciones «en vivo». Desarrollamos guías de facilitación con educadorxs populares para recuperar saberes en pos de la justicia social y de género, incluso sobre un tópico tan aparentemente opaco como los flujos financieros ilícitos. Auspiciamos blogs y opiniones sobre cómo los grupos feministas obtienen fondos y recursos, y señalamos las amenazas que enfrentan nuestros sistemas de derechos humanos.

Dentro de AWID, pusimos en práctica y aprendimos de nuestro enfoque de liderazgo compartido, y relatamos la historia de las dificultades y tribulaciones de dirigir conjuntamente una organización global virtual. No tenemos una respuesta definitiva sobre cómo es un liderazgo feminista, pero un año más tarde sabemos que el compromiso continuo con la experimentación y el aprendizaje colectivos nos ha permitido seguir construyendo una organización con la cual nos entusiasma contribuir.

Al recordar este año, queremos agradecer a todxs nuestrxs amigxs y promotorxs, colegas y compañerxs, que han aportado su tiempo y han compartido su bagaje de conocimiento y sabiduría con nosotrxs. Queremos agradecer a nuestrxs afiliadxs, que han ayudado a construir nuestro plan estratégico y se han unido a nosotrxs para formular demandas feministas. No podríamos hacer este trabajo sin ustedes.