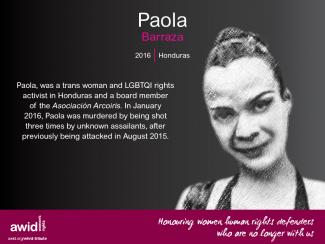

Paola Barraza

WHRDs are self-identified women and lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LBTQI) people and others who defend rights and are subject to gender-specific risks and threats due to their human rights work and/or as a direct consequence of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

WHRDs are subject to systematic violence and discrimination due to their identities and unyielding struggles for rights, equality and justice.

The WHRD Program collaborates with international and regional partners as well as the AWID membership to raise awareness about these risks and threats, advocate for feminist and holistic measures of protection and safety, and actively promote a culture of self-care and collective well being in our movements.

WHRDs are exposed to the same types of risks that all other defenders who defend human rights, communities, and the environment face. However, they are also exposed to gender-based violence and gender-specific risks because they challenge existing gender norms within their communities and societies.

We work collaboratively with international and regional networks and our membership

We aim to contribute to a safer world for WHRDs, their families and communities. We believe that action for rights and justice should not put WHRDs at risk; it should be appreciated and celebrated.

Promoting collaboration and coordination among human rights and women’s rights organizations at the international level to strengthen responses concerning safety and wellbeing of WHRDs.

Supporting regional networks of WHRDs and their organizations, such as the Mesoamerican Initiative for WHRDs and the WHRD Middle East and North Africa Coalition, in promoting and strengthening collective action for protection - emphasizing the establishment of solidarity and protection networks, the promotion of self-care, and advocacy and mobilization for the safety of WHRDs;

Increasing the visibility and recognition of WHRDs and their struggles, as well as the risks that they encounter by documenting the attacks that they face, and researching, producing, and disseminating information on their struggles, strategies, and challenges:

Mobilizing urgent responses of international solidarity for WHRDs at risk through our international and regional networks, and our active membership.

With over ten years of finance experience, Lucy has devoted her career to for profit and furthering nonprofit missions. She also worked and volunteered at non-for-profit organizations. From the fast-paced world of Finance, Lucy has passion for staying tuned with tech skills in the finance field. Lucy joined AWID in 2014. During her spare time she enjoys music, traveling, and variety sports.

Fotos realizadas por Mariam Mekiwi

Diseñadora de vestuario y modelo: El Nemrah

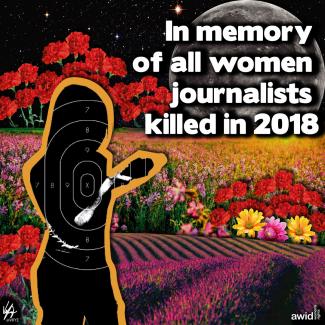

Just like women have learned to avoid dark streets for their safety, women journalists are forced to avoid reporting certain stories as a result of online harassment.

Harassment is not part of the job description and should be called out and challenged at every turn to ensure these important voices are not silenced.

This tribute to journalists was made on behalf of IFEX

Kasia viene apoyando la labor de los movimientos feministas y por la justicia social desde hace 15 años. Antes de sumarse a AWID, se lideró las acciones de política e incidencia ActionAid y Amnistía Internacional, a la vez que participaba en procesos de organización feministas y de distintas agrupaciones por la justicia social en Polonia, en pro del acceso al aborto y contra la violencia en las fronteras europeas. Es una apasionada del financiamiento para la movilizaciónfeminista en toda su audacia, riqueza y diversidad. Reparte su tiempo entre Varsovia y su aldea comunitaria de trabajo artesanal en el bosque. Le encanta tomar saunas y adora con locura a su perro Wooly.

What helped me was, I loved the work of going into the country and documenting people’s knowledge. So I left the comfort. I became a country director of a regional organisation that was queer as fuck!

“[She] was a person who was characterized by her hard work in favor of the defense of human rights and the construction of peace in Nariño, especially in the municipality of Samaniego-Nariño.”

- Jorge Luis Congacha Yunda for Página10

She focused on civil and political rights, issues of impunity and justice, and contributed to uncovering the abuse of power, including corruption. She also participated in peacebuilding projects in her hometown Samaniego, such as the Municipal Peace Council and the Municipal Women’s Board.

Paula received death threats after exposing the irregular handling of resources and complaining about acts of corruption at the Lorencita Villegas Hospital in the Nariñense municipality. She was murdered on 20 May 2019, when two men approached and shot her at close range.

Faye est une féministe panafricaine passionnée, engagée dans les mouvements pour les droits des femmes, la justice raciale, les droits des migrant·e·s et des travailleur·euse·s, et la justice environnementale. Son activisme s'appuie sur l'héritage de la lutte contre l'apartheid en Afrique du Sud et de ses suites au Zimbabwe.

En 2019, Faye rejoint l'AWID en tant que Directrice des Finances, des Opérations et du Développement. Elle s’est efforcée de garantir que l’AWID respecte les principes et les valeurs féministes dans toutes ses opérations. Elle y apporte plus de 20 années d’expérience en leadership féministe, en stratégie et autres aspects du développement organisationnel et financier.

Faye est membre engagée du conseil d'administration de Urgent Action Fund-Africa et d'autres organisations de défense des droits des femmes. Auparavant, elle a occupé des postes de responsable des finances et des opérations chez Pediatric Adolescent Treatment for Africa et JASS - Just Associates Inc. en Afrique australe. Elle a également occupé des postes de direction chez International Computer Driving Licence (ICDL) en Afrique centrale et australe. Elle est titulaire d'une licence en sciences comptables de l'Université d'Afrique du Sud ainsi que membre du Southern African Institute for Business Accountants.

"Estas conversas para mí hacen parte de las más recientes expresiones de amor que la vida me ha permitido. Formas que no sabía que eran posibles, que se quedan afuera de un taller o de un espacio militante, de un salón de clases o de una oficina de trabajo..."

Contenu lié

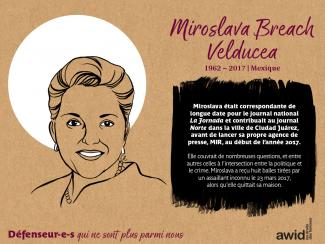

RFI: Une journaliste tuée au Mexique, la troisième en moins d’un mois

Carol Thomas fue una pionera en el trabajo por los derechos sexuales y reproductivos de las mujeres en Sudáfrica. Fue una ginecóloga de gran talento y la fundadora del WomenSpace [EspacioDeMujeres].

No sólo las empleó en su práctica, sino que también abogó por proporcionar formas no tradicionales de asistencia sanitaria a las mujeres, ofreciendo servicios de alta calidad, empáticos y accesibles.

"Ella recibió no sólo la alegría de los embarazos y la llegada de nuevxs bebés, sino también la ansiedad que puede generar la infertilidad, un parto prematuro, el cáncer femenino, así como también la angustia de los abortos espontáneos y lxs mortinatxs". Helen Moffett

Carol pensó en nuevos paradigmas cuyo centro de atención fuesen las necesidades de las mujeres con menor acceso a los servicios y derechos que puede aportar una sociedad:

"El entorno socioeconómico imperante en el que nos encontramos hoy se traduce en una carga desproporcionada de enfermedades y desempleo que las mujeres tienen que soportar... Como mujer negra, desfavorecida en el pasado, tengo una idea clara de lo que está sucediendo en nuestras comunidades". - Carol Thomas

La innovadora y multipremiada empresa social de Carol, "“iMobiMaMa”, utilizaba los quioscos móviles y la tecnología interactiva para conectar directamente a las mujeres con servicios de salud prenatal y reproductiva, información y apoyo en las comunidades de toda Sudáfrica.

Carol apoyó a las mujeres tanto en los embarazos deseados como en los no deseados, y fue mentora de muchxs enfermerxs y doctorxs a lo largo de su vida.

Fue calificada, además, como ginecóloga de referencia "para las personas trans que podían recibir de ella una atención afirmativa. Ella supo cómo manejarse cuando muchas personas no tenían todavía en claro el lenguaje o los pronombres. Sus mantas calientes, su capacidad para escuchar y decir lo que necesitabas oír eran muy reconfortantes." -Marion Lynn Stevens.

Carol Thomas falleció el 12 de abril de 2019 a causa de una serie de complicaciones tras un doble trasplante de pulmón, en el punto más álgido de su carrera profesional.

Los homenajes que llegaron después de su muerte inesperada se refieren a ella de muchas formas: como " modelo a seguir, mujer guerrera, innovadora, líder dinámica, rompe-moldes, dínamo, científica brillante, doctora compasiva".

Sin duda, Carol Thomas será recordada y honrada por ser todo esto y mucho más.

Elina is a young afro-Dominican intersectional feminist and human rights lawyer, committed to use her voice and skills to build a more just, empathic and inclusive world. She started Law school at 16, convinced it would give her the tools to understand and promote social justice. After a J.D. in the Dominican Republic, she pursued an LL.M. in Public International Law and Human Rights in the UK as a Chevening Scholar. She was the only Latinx-Caribbean woman in her class, graduating with honours.

Elina has worked at the intersection of human rights, gender, migration and policy, from government, grassroots collectives and international organizations. She helped litigate cases on gender-based violence before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. As a member of the Youth Advisory Panel of UNFPA, she contributed to strengthening sexual and reproductive rights in the Dominican Republic. She co-led Amnesty International’s first campaign on sex workers’ rights in the Americas, developing strong partnerships with sex-worker led organizations and using Amnesty’s position to amplify women human rights defenders and sex workers’ voices.

Elina is part of Foro Feminista Magaly Pineda and the Global Shapers Community. She speaks Spanish, French and English. Thanks to her diverse background, Elina brings strong governance and strategic planning skills, substantive expertise on the United Nations and regional human rights mechanisms and her bold determination to keep AWID as an inclusive organization for all women, especially young and Caribbean feminists. With these offerings, joins a global sisterhood of feminist badasses, where she can keep nurturing her feminist leadership and never again feel alone in her path.

حلقة نقاش | التمتّع عبر الحدود

مع لينديوي راسيكوالا وليزي كياما وجوفانا دروديفيتش ومَلَكة جران

Mereani Naisua Senebici, que l’on appelait aussi « Sua », a été membre de l’Association des jeunes femmes chrétiennes (YWCA) des Fidji pendant de longues années.

En plus d’avoir travaillé avec divers groupes de femmes dans des contextes multiraciaux, ruraux et urbains, elle s’est impliquée dans le soutien et la promotion des droits des femmes et des jeunes femmes.

Au YWCA de Lautoka, elle travaillait avec des femmes d’origine indienne et comptait parmi les pionnières du développement de la pratique sportive et la participation des femmes et athlètes trans localement.

« Les membres du YWCA des Fidji ont profondément aimé Sua pour son dévouement et son soutien inébranlable envers tous les efforts déployés par l’organisation » – Tupou Vere

Mereani faisait partie de la House of Sarah (HoS), une initiative de l’Association of Anglican Women (AAW) lancée en 2009, un organisme de sensibilisation autour des violences basées sur le genre et de soutien des femmes victimes de violence. Ayant commencé sa pratique en tant que bénévole dévouée, elle offrait notamment son soutien aux femmes dans tout le Pacifique.

Mereani s’est éteinte en 2019.

« Une personne qui aimait les gens, qui était présente sur tous les fronts de l’autonomisation des femmes et du travail du mouvement au niveau communautaire. Repose en paix, Sua. » – Tupou Vere

Jessica es une artista activista queer de Toronto (Canadá), aunque actualmente reside en Bulgaria. Posee más de 15 años de experiencia de trabajo en la respuesta al VIH en las intersecciones del género y el VIH con poblaciones clave (trabajadoras/es sexuales, mujeres que usan drogas, comunidades LGBTQI, personas privadas de su libertad y, desde luego, personas que viven con el VIH). A Jessica le encanta la construcción de movimientos y pensar, organizar y trazar estrategias para intervenciones artísticas. Un divertido proyecto que comenzó en 2013 fue LOVE POSITIVE WOMEN, en el que participan más de 125 agrupaciones y organizaciones comunitarias de todo el mundo. Este tiene lugar cada año entre el 1 y el 14 de febrero para celebrar a las mujeres que viven con el VIH en sus comunidades.