Juvy Magsino

Women human rights defenders (WHRDs) worldwide defend their lands, livelihoods and communities from extractive industries and corporate power. They stand against powerful economic and political interests driving land theft, displacement of communities, loss of livelihoods, and environmental degradation.

Extractivism is an economic and political model of development that commodifies nature and prioritizes profit over human rights and the environment. Rooted in colonial history, it reinforces social and economic inequalities locally and globally. Often, Black, rural and Indigenous women are the most affected by extractivism, and are largely excluded from decision-making. Defying these patriarchal and neo-colonial forces, women rise in defense of rights, lands, people and nature.

WHRDs confronting extractive industries experience a range of risks, threats and violations, including criminalization, stigmatization, violence and intimidation. Their stories reveal a strong aspect of gendered and sexualized violence. Perpetrators include state and local authorities, corporations, police, military, paramilitary and private security forces, and at times their own communities.

AWID and the Women Human Rights Defenders International Coalition (WHRD-IC) are pleased to announce “Women Human Rights Defenders Confronting Extractivism and Corporate Power”; a cross-regional research project documenting the lived experiences of WHRDs from Asia, Africa and Latin America.

"Women Human Rights Defenders confronting extractive industries: an overview of critical risks and Human Rights obligations" is a policy report with a gender perspective. It analyses forms of violations and types of perpetrators, quotes relevant human rights obligations and includes policy recommendations to states, corporations, civil society and donors.

"Weaving resistance through action: Strategies of Women Human Rights Defenders confronting extractive industries" is a practical guide outlining creative and deliberate forms of action, successful tactics and inspiring stories of resistance.

The video “Defending people and planet: Women confronting extractive industries” puts courageous WHRDs from Africa, Asia, and Latin America in the spotlight. They share their struggles for land and life, and speak to the risks and challenges they face in their activism.

Challenging corporate power: Struggles for women’s rights, economic and gender justice is a research paper outlining the impacts of corporate power and offering insights into strategies of resistance.

AWID acknowledges with gratitude the invaluable input of every Woman Human Rights Defender who participated in this project. This project was made possible thanks to your willingness to generously and openly share your experiences and learnings. Your courage, creativity and resilience is an inspiration for us all. Thank you!

Día 1

L’AWID a fait ses débuts en 1982 et s’est transformée au fil du temps.

Lire « From WID to GAD to Women's Rights: The First 20 Years of AWID » (disponible uniquement en anglais).

Related content

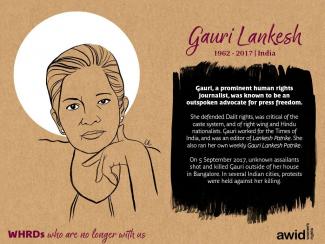

Reporters without Borders: India: Prominent woman journalist gunned down in Bangalore

BBC: Gauri Lankesh: Indian journalist shot dead in Bangalore

Committee to Protect Journalists: Gauri Lankesh Killed

BBC: Gauri Lankesh: Murdered Indian journalist in her own words

The Guardian: The murder of journalist Gauri Lankesh shows India descending into violence

Financial Times - Gauri Lankesh, journalist and activist, 1962-2017

The New York Times: Why was Gauri Lankesh killed?

(¡con invitades especiales!)

📅Martes 12 de marzo

🕒6:00 p. m. - 9:30 p. m. EST

🏢 Blue Gallery, 222 E 46th St, New York

Entrada solo con confirmación previa

Nació en Bahía, la parte noreste de Brasil. Es inmigrante, activista social y madre de 8 hijxs.

Carmen experimentó la falta de vivienda a los 35 años, después de migrar sola a São Paulo. Esto la llevó a convertirse en una feroz defensora de las comunidades vulnerables, marginalizadas e invisibilizadas más afectadas por la crisis de la vivienda. Eventualmente se convirtió en una de las fundadoras del MSTC en 2000.

Como organizadora política visionaria y líder actual del MSTC, el trabajo de Carmen ha puesto al descubierto la crisis de la vivienda de la ciudad y ha inspirado a otrxs sobre diferentes formas de organizar y gestionar las ocupaciones.

Se mantuvo firme al frente de varias ocupaciones. Uno de ellos es la Ocupación 9 de Julho, que ahora sirve como escenario para la democracia directa y un espacio donde todxs pueden ser cuidadxs, escuchadxs, apreciadxs y trabajar juntos.

Carmen ha sido celebrada durante mucho tiempo por su audacia al devolver la vida a edificios abandonados en el corazón de São Paulo.

¡Si quieres saber más sobre Carmen, puedes seguir su cuenta de Instagram!

We and cannot review funding proposals or requests.

We encourage you to browse our list of donors that may potentially fund your women's rights organizing.

More resources are available from the Priority Area “Resourcing Feminist Movements”

Contenido relacionado

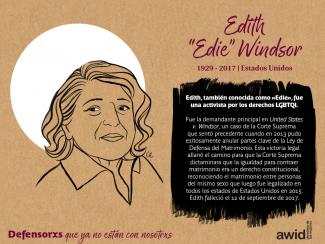

El Mundo: Muere Edith Windsor, la activista que logró que la Justicia de EEUU reconociera el matrimonio gay

L’enquête s’adresse aux groupes, organisations et mouvements qui travaillent spécifiquement, ou principalement, à la défense des droits des femmes, des personnes LBTQI+ et pour la justice de genre dans tous les contextes, à tous les niveaux, dans toutes les régions. Si c’est un des principaux piliers du travail de votre groupe, collectif, réseau ou tout autre type d’organisation, que votre structure soit déclarée ou non, récemment constituée ou plus ancienne, nous vous invitons à participer à cette enquête.

*Nous ne collectons pas les réponses à titre individuel ou de fonds féministes et pour les femmes à l’heure actuelle.

En savoir plus sur l'enquête :

Consultez la foire aux questions

De hecho, el 38% de nuestra membresía tienene menos de 30 años de edad.

Creemos que lxs activistas jóvenes son el presente y el futuro de la lucha por los derechos de las mujeres. Mediante nuestro programa «Activismo Joven Feminista» que atraviesa todos los aspectos de nuestro trabajo, promovemos a líderes jóvenes en el movimiento mundial por los derechos de las mujeres. A la vez, al definir a este programa como una de nuestras Áreas Prioritarias, contribuimos con nuevos análisis a los debates actuales para asegurarnos que las jóvenes activistas feministas sean capaces de articular sus prioridades y darle voz a los temas que les preocupan.

Pour revendiquer votre pouvoir en tant qu’experte sur la situation du financement des mouvements féministes.

When walking in the heart of the Raval district of Barcelona, you might come across Metzineres, a feminist cooperative by and for womxn2 who use drugs surviving multiple situations of vulnerability.

Imagine a place free of stigma, where womxn can be safe. A safe place that provides shelter, support and accompaniment for womxn whose rights are systematically violated by the war on drugs and those who experience violence, discrimination and repression as a result.

Right outside the entrance, passers by and visitors are greeted with a massive chalkboard that outlines tips, tricks, wishes and drawings by drug users. There is also a calendar that boasts a range of activities self-organized by the Metzineres community. Whether it’s hairdressing and cosmetics workshops, radio shows, theater, communal meals offered to the community, or self-defense classes - there is always something going on.

The cooperative provides safe consumption sites as well as utilities that cover people’s basic needs. There are beds, storage spaces, showers, toilets, washing machines and a small outdoor terrace where people can chill or have a goat gardening.

Metzineres operates within a harm reduction framework, which attempts to reduce the negative consequences of using drugs. But harm reduction is so much more than a set of practices: it is a politics anchored in social justice, dignity and rights for people who use drugs.

2 Womxn is a term used by the collective to describe cis and trans women as well as non-binary peopleNous vous invitons à explorer nos sections Domaines prioritaires et Informez-vous ou utlisez l'outil de recherche pour trouver des informations sur un suject spécifique.

Nous recommendons particulièrement la consultation de notre boîte à outils « Où est l’argent pour les droits des femmes ? » (« Where Is The Money for Women's Rights? », WITM). Cette boîte à outils est une méthodologie de recherche autogérée pour soutenir les individus et les organisations qui souhaitent mener leur propre recherche sur les tendances de financement en adaptant la méthodologie de recherche de l’AWID à une région, une question ou une population spécifique.