Que se passe-t-il lorsqu’une féministe africaine décède?

Le genre d’histoires que nous devons oser nous raconter

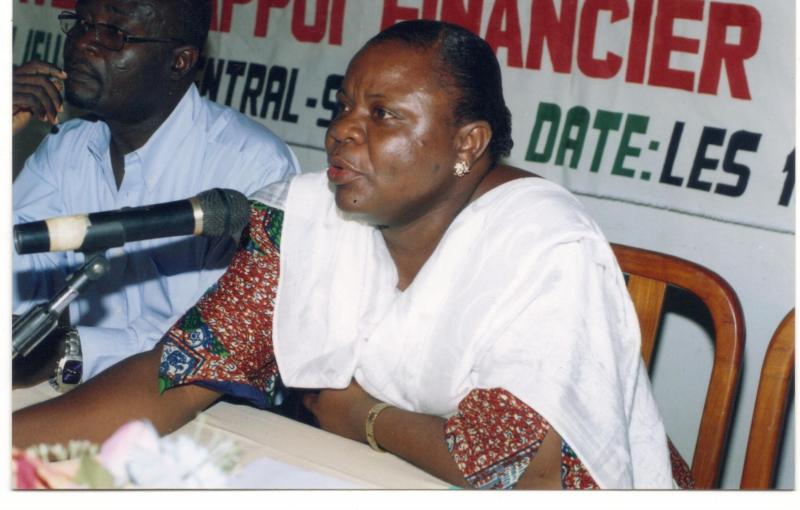

Massan d’Almeida est une organisatrice féministe du Togo, fondatrice et Directrice éxécutive sortante du Réseau des Organisations Féminines de l’Afrique Francophone (ROFAF). Le ROFAF est un membre institutionnel de l’AWID, dont l’action est centrée sur le renforcement du réseautage et le soutien aux organisations et activistes féministes en Afrique francophone.

Elle est décédée seule

Il n’y a pas si longtemps, Elise Ama Esso Lare, une militante des droits humains africaine de notre cercle, est décédée à l’âge de 51 ans des suites d’une longue maladie. Elle n’avait gagné aucun salaire dans le cadre de son militantisme ; au cours des denières années de sa vie, à cause de sa longue maladie, elle avait dépensé tout son argent.

Combien d’entre nous, dans nos cercles de militant-e-s des droits humains et féministes, étaient au courant de cette situation ? Très peu. Nous ne disposons d’aucun mécanisme permettant de faire circuler ce genre d’information. Les détails sur lesquels nous échangeons ont généralement trait aux invitations à des ateliers et autres informations pratiques. Et que faisons-nous lorsque l’un-e d’entre nous a besoin d’aide ? Absolument rien. Les militant-e-s comme nous n’ont aucune couverture médicale, ni structure pour prendre soin de nous-mêmes, donc lorsque l’un-e d’entre nous tombe malade, il ou elle paie de sa poche.

Cette militante qui vient de décéder... qui l’a enterrée ? Qui a assisté à ses obsèques ? Combien d’autres militant-e-s de son cercle étaient présent-e-s pour lui rendre un dernier hommage ? Très peu. Ce fut extrêmement perturbant.

À travail non rémunéré, ressources qui s’amoindrissent

Parlons des facteurs économiques.

Parlons de l’avalanche de conférences mondiales sur les femmes et les mouvements internationaux pour les droits des femmes qui a débuté en 1975. Mexico. Beijing. Nairobi.

Cette vague a déclenché une accélération de soutien de courte durée aux mouvements féministes, de sorte que, tout d’un coup, il semblait y avoir de l’argent pour la défense des droits des femmes. L’occasion, pour certain-e-s, de gagner un peu d’argent. Lancer une ONG, obtenir une ou deux subventions, générer un peu de travail, gérer le reste. Pour d’autres, ce fut l’occasion d’obtenir des ressources financières, de voyager, de participer à quelques conférences, toucher des indemnités quotidiennes sur quelques jours.

La réalité est très différente. S’il ne fait aucun doute que les financements sont plus nombreux aujourd’hui, les ressources allouées spécifiquement aux droits des femmes demeurent rares. Un rapide coup d’œil permet de constater que nombre d’organisations n’ont qu’un nom ; l’absence de financement depuis des années les empêchant de mener une quelconque action. Certaines personnes travaillent, malgré tout, par pure passion : certaines motivées par leur formation scolaire ou intellectuelle, ou par la rencontre d’autres militant-e-s lors de réunions, séminaires ou conférences. Elles se disent alors qu’elles « aussi peuvent faire quelque chose ». Il arrive que leur entourage les encourage, en les incitant à créer leur propre ONG, parce que « c’est bien mieux que de travailler pour l’ONG de quelqu’un d’autre ».

La multiplication du nombre d’organisations et de militant-e-s impacte la qualité du travail, notamment car les capacités et les ressources sont très insuffisantes et que, de ce fait, la motivation à mettre son action féministe au service d’une cause est également faible.

L’histoire de la création des ONG féministes

Les ONG sont-elles le meilleur vecteur pour l’action féministe ? Outre les structures étatiques, le fait est que les ONG semblent constituer le seul espace dans lequel il soit possible de soutenir certaines initiatives. Le paradigme ONG-société civile est un format apparu dans le sillon des conférences internationales sur les femmes depuis Mexico en 1975. À l’époque, de nombreux pays du monde commençaient à investir dans des ministères de la Femme, en puisant dans leurs enveloppes d’aide internationale. Mais même ainsi, peu de ces ministères avaient assez de budget pour mener à bien des actions concrètes. Et le cumul d’une mauvaise gouvernance et de la corruption a entraîné la nécessité de disposer d’un canal de redistribution des ressources disponibles pour la défense des droits humains des femmes. C’est alors que les ONG et autres organisations internationales sont entrées en scène.

Les grandes entreprises peuvent désormais faire des demandes directes de subventions auprès de nos bailleurs de fonds historiques. Et elles reçoivent souvent plus de fonds que les ONG, peut-être parce qu’elles présentent un modèle qui privilégie la recherche du profit et disposent de mécanismes et d’outils qui facilitent cette génération de profit. La gestion axée sur les résultats, par exemple, est un modèle de gestion provenant du secteur privé si répandu que même les ONG s’en sont emparées. Et du fait de nos capacités institutionnelles actuelles, les ONG ressemblent davantage à des « personnes non gouvernementales » qu’à des « organisations non gouvernementales ». Elles manquent de ressources et de structure, ce qui alimente le cercle vicieux du « moins l’on dispose de financement, moins l’on reçoit de nouveaux financements ».

Mais où est donc l’argent ?

Laissez-moi vous raconter une autre histoire : J’étais à un atelier, l’autre jour, à l’occasion duquel nombre des militant-e-s présent-e-s étaient a priori réuni-e-s pour soutenir une organisation. Mais certain-e-s participant-e-s étaient en fait occupé-e-s à autre chose : Elles-Ils étaient envieux-ses à propos de la subvention que l’organisation principale avait reçue - et pas nous. Elles-Ils essayaient de calculer le montant des financements vraiment dépensé, et ce qui allait directement dans les poches des organisatrices-teurs.

Ces participant-e-s, de ce fait, peu enthousiastes à s'engager davantage. Personne ne souhaitait continuer à s’impliquer. La raison initiale de notre rassemblement ce jour-là est ainsi passée au deuxième plan. Il ne s’agissait plus que (du manque) d’argent.

De plus, la qualité et la quantité de financement que nous recevons ces jours-ci ne nous permettent pas d’assurer la pérennité de nos organisations. Nous comprenons bien que c’est parce que les gouvernements et institutions doivent justifier des subventions qu’ils nous accordent auprès de leurs citoyen-ne-s, mais cela est une toute autre histoire. Ce qui est clair est qu’ils peuvent décider de venir ici et de « travailler sur le terrain » par eux-mêmes, ou nous laisser mettre nos connaissances et notre expertise à profit pour faire le travail. Je pense personnellement qu’il s’agit d’une violation de notre droit à un travail décent rémunéré, et qu’il faut que nous osions parler de cela. Il est inconcevable que nous n’en parlions pas plus souvent.

C’est là le genre d’histoires que nous devons oser nous raconter

Je pense à mes collègues, à moi-même et à la pérennité de nos mouvements. Nous semblons aujourd’hui tenir solidement debout, mais le jour où quelque chose nous arrive, nous ne savons pas ce que nous deviendrons, ni notre entourage. Et cela me fait réfléchir à deux fois au genre de travail que nous réalisons, aux ressources dont nous disposons pour travailler, et à la manière dont nous travaillons. Tout le monde doit savoir ce qui se passe lorsqu’un-e militant-e des droits humains africaine de notre cercle décède.

À propos du ROFAF

Le Réseau des Organisations Féminines d’Afrique Francophone (RORAF) est une ONG internationale fondée en 2006, avec pour objectif de mobiliser les fonds pour le travail des droits des Femmes en Afrique Francophone et d'apporter un appui technique et financier à ses organisations membres. Le ROFAF est membre institutionnel de l’AWID depuis 2008, et a présenté une session sur son expérience en matière de réseautage pour œuvrer en faveur de la sécurité des femmes et des filles et de leadership dans les situations de conflits et post-conflits, à l’occasion du Forum de l’AWID en 2016.

Le Réseau des Organisations Féminines d'Afrique Francophone (ROFAF) est une organisation internationale non gouvernementale apolitique et à but non lucratif créé le 28 juillet 2006 et dont la mission est de mobiliser les ressources financières pour faire avancer les droits des femmes en Afrique francophone. Ses objectifs sont de :

- Appuyer financièrement la mise en oeuvre des initiatives de ses organisations membres ;

- Renforcer les capacités institutionnelles de ses organisations membres ;

- Oeuvrer au respect des droits des femmes en Afrique francophone.