Finding my voice and my identity as a Sierra Leonean feminist

As part of AWID member profile stories, Ngozi Cole tells about her journey and how she found her identity as a feminist.

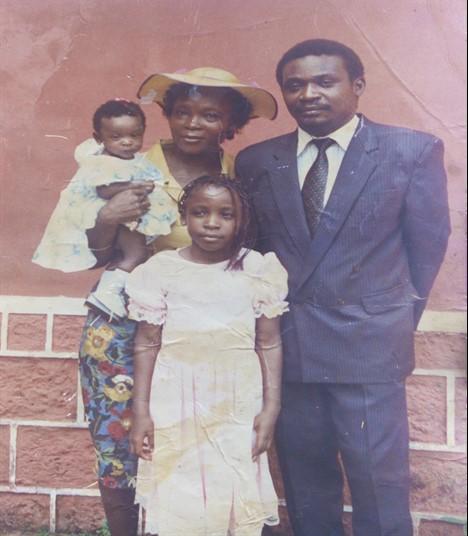

My earliest joyful memories were being on my mother’s back. The cozy warmth of her cotton wrapper was comforting.

Up until I was five years old I would always jump on her back so that she would patiently wrap me up into a cocoon, even when she would mumble that I was getting “too big” for that. Around that time, our lives changed forever. In 1997, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebels invaded Freetown, and home as I knew it was ripped away from me.

My mother fled with me and my older sister to neighboring The Gambia, where we would start life as refugees. I was only five when we fled and had little understanding of why I had to leave behind my friends, cousins, father, and toys. I tried to adapt to a new home and my mother made sure her daughters were shielded from the many realities of marginalization and hardship that come with being a refugee in a foreign country. I learned how to speak wolof, made friends quickly and soon many things became familiar - smells and sounds started to feel like they could be my piece of home.

The following year we moved back to Sierra Leone after a brief respite of peace, and it seemed as though peace had finally come, even though it was a shaky stillness. We tried to settle into our old life again, hoping that a peace agreement between warring factions would work out. Life seemed stable for a while and for a moment I started to forget my life in The Gambia - until January 6th, 1999 when the rebels re-entered Freetown.

To become unsettled again, to face the trauma of war again, was much worse than the last time I experienced it. This time I was more aware and slightly older, and it left a feeling of trying to catch something that was floating away from me. We fled to The Gambia again, and for two more years there it seemed like I had found home, and settled into my identity as a refugee, or as an “alien”, as we were called in The Gambia.

In 2002, we decided to return to Sierra Leone again, for good this time, we hoped.

My identity shifted again when I started high school in Freetown at the Annie Walsh Memorial School. I didn’t know my own national anthem, I had forgotten some of the words in the national pledge, and I knew that my accent wasn’t “quite right”. In the first grade of high school, some of my classmates asked if I was really Sierra Leonean. Even though the security of home and the familiar had been snatched, dangled in front of me, only to be snatched away from me again, I was desperate to lose that feeling of displacement, of feeling less than, not a full citizen, a refugee.

After formal high school in Sierra Leone I won a scholarship to attend a pan African school -The African Leadership Academy in Johannesburg. Afterwards, I went on to Wooster, a small town in the middle of Ohio, to attend the College of Wooster, a small private liberal Arts School not too far from Cleveland. I took some classes in philosophy and political science which, along with the academia, gave me the tools to articulate another part of myself - my identity as a feminist.

During my early teenage years, I had been fully convinced feminists were women who harbored anger toward men, man-haters.

At around 16, I had started thinking very radically about my position as a young girl, in what I considered (and still do) a predominantly patriarchal society. I was inspired by women’s rights activists, women who constantly fought for political equality in Sierra Leone, equal economic and property rights, and rallied against female genital mutilation. But I still considered “feminism” too extreme. In 2013, I got the chance to be part of a fellowship in Ghana, of young African women living on the continent and in the diaspora, many of them feminists, who were making a change in their respective communities.

During my time in Ghana, I met Leymah Gbowee and Taiye Selasi, brave women who had also battled with identity, and solidly identified with feminism. Upon my return to the United States that summer, I started to blog about my journey as an African woman living in the mid-west, and also about my fully embracing feminism. I was able to find a voice for myself, a voice that was no longer shy to debate and argue with my peers about issues affecting women, both on campus and the outside world. Feminism influenced my writings, and I was featured on an African women’s podcast to talk about the stifling of African women’s sexuality. My blog posts on body shaming and rape culture and shame were widely shared on social media.

Even after college I continued to find ways to embrace this part of myself, and as I am growing and fully embracing it, I know now that feminism isn’t a “part” of me, it is fundamental to my survival as I navigate life’s journey as a young Sierra Leonean woman. These days I find outlets to write about women’s rights concerning mental health and reproductive rights in Sierra Leone.