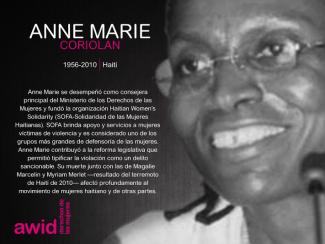

Anne Marie Coriolan

Over the past few years, a troubling new trend at the international human rights level is being observed, where discourses on ‘protecting the family’ are being employed to defend violations committed against family members, to bolster and justify impunity, and to restrict equal rights within and to family life.

The campaign to "Protect the Family" is driven by ultra-conservative efforts to impose "traditional" and patriarchal interpretations of the family, and to move rights out of the hands of family members and into the institution of ‘the family’.

Since 2014, a group of states have been operating as a bloc in human rights spaces under the name “Group of Friends of the Family”, and resolutions on “Protection of the Family” have been successfully passed every year since 2014.

This agenda has spread beyond the Human Rights Council. We have seen regressive language on “the family” being introduced at the Commission on the Status of Women, and attempts made to introduce it in negotiations on the Sustainable Development Goals.

AWID works with partners and allies to jointly resist “Protection of the Family” and other regressive agendas, and to uphold the universality of human rights.

In response to the increased influence of regressive actors in human rights spaces, AWID joined allies to form the Observatory on the Universality of Rights (OURs). OURs is a collaborative project that monitors, analyzes, and shares information on anti-rights initiatives like “Protection of the Family”.

Rights at Risk, the first OURs report, charts a map of the actors making up the global anti-rights lobby, identifies their key discourses and strategies, and the effect they are having on our human rights.

The report outlines “Protection of the Family” as an agenda that has fostered collaboration across a broad range of regressive actors at the UN. It describes it as: “a strategic framework that houses “multiple patriarchal and anti-rights positions, where the framework, in turn, aims to justify and institutionalize these positions.”

El Nemrah

En 2021, l’AWID, comme beaucoup d’autres organisations, a dû faire face aux répercussions de la pandémie mondiale en cours sur notre façon de travailler et notre rôle en ces temps particuliers. L’année nous a appris trois leçons essentielles sur la façon de traverser cette période en tant qu’organisation mondiale de soutien au mouvement féministe.

Téléchargez le rapport annuel 2021

Notre expérience en 2021 nous a permis de constater que l’AWID jouait un rôle important et quelque peu unique dans la création et le maintien d’une communauté féministe mondiale transcendant les identités et les thèmes.

Je vais être honnête : lorsque Angélica et Fabi m’ont proposé de créer une collection de textes érotiques écrits par des femmes noires, j’ignorais ce que c’était que de produire un recueil. Je maîtrisais le thème de l’érotisme, mais créer un recueil…

Con más de 10 años de experiencia en finanzas, Lucy ha dedicado su carrera a misiones con y sin fines de lucro. También ha prestado trabajo voluntario para organizaciones sin fines de lucro. Desde el acelerado mundo de las finanzas, Lucy siente pasión por estar al día con las competencias tecnológicas asociadas con este ámbito. Lucy se incorporó a AWID en 2014. En su tiempo libre disfruta de la música, de viajar y de practicar una variedad de deportes.

.

Les hôpitaux sont des institutions, des sites vivants du capitalisme, et ce qui se joue lorsque quelqu’un est censé se reposer est un microcosme du système lui-même.

Kasia soutient le travail des mouvements féministes et de justice sociale depuis 15 ans. Avant de rejoindre l'AWID, Kasia dirigeait les politiques et le plaidoyer d’ActionAid et d’Amnesty International, tout en se mobilisant avec des féministes et des groupes de justice sociale en Pologne pour l'accès à l'avortement et la lutte contre les violences aux frontières européennes. Kasia est passionnée par le ressourcement des organisations féministes dans tout leur courage, leur richesse et leur diversité. Elle partage son temps entre Varsovie et son village communautaire de bricolage dans la forêt. Elle adore les saunas et aime follement son chien Wooly.

Related content

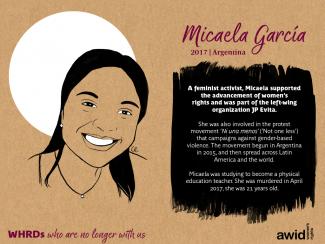

TeleSUR: Outrage Shakes Argentina After Murder of Anti-Femicide Activist

مع استمرار الرأسمالية الأبوية الغيريّة في دَفعِنا نحو الاستهلاكية والرضوخ، نجد نضالاتنا تُعزَل وتُفصَل عن بعضها الآخر من خلال الحدود المادّية والحدود الافتراضية على حدٍّ سواء. ومع تحدّياتٍ إضافية يفرضها علينا وباءٌ عالميٌّ علينا تجاوزه، أصبحت سياسة فرِّق تَسُد مواتية للاستغلال المتزايد في مجالات عدّة.

ومع ذلك، أخذَنا «ابدعي، قاومي، غيٍّري: مهرجان للحراكات النسوية»، الذي نظّمته جمعية «حقوق المرأة في التنمية» AWID في الفترة ما بين 1 أيلول/ سبتمبر وحتى 30 أيلول/ سبتمبر 2021، في رحلةٍ حول ما يعنيه تجسّد حيواتنا في المساحات الافتراضية. اجتمعَت معنا في المهرجان ناشطات نسويات من حول العالم، لأجل مشاركة خبراتهن حول المقاومة والحرّيات المُنتَزَعة بصعوبة، والتضامن العابر للحدود، وكذلك لتوضيح الشكل الذي يمكن أن يبدو عليه التكاتف العابر للحدود القومية.

يحمل هذا التكاتف إمكانية مقاومة الحدود، ناسجاً رؤية لمستقبل تحويلي، لأنه سيكون إلغائيًا ومناهضًا للرأسمالية. على مدار شهر، وعبر البُنى التحتية الرقمية التي احتللناها بكويريّتنا ومقاومتنا وخيالاتنا، بيّن لنا المهرجان طريقةً للانحراف عن الأنظمة التي تجعلنا متواطئات في قهر أنفسنا وأخريات/ آخرين.

بالرغم من أن أودري لورد علّمتنا أنّ أدوات السيّد لن تهدم أبدًا منزله، بيّنت لنا سارة أحمد أنه بإمكاننا إساءة استخدام تلك الأدوات عن سبق إصرار. أصبح من الممكن تخيّل خلخلة في واقع الرأسمالية الأبوية الغيريّة، لأننا خلقنا مساحة للاحتشاد، بالرغم من كلّ الأشياء الأُخرى التي تتطلّب وقتنا.

إذا أدركنا الاحتشاد باعتباره أحد أشكال التمتّع، عندها سيصبح من الممكن خلق الرابط بين المتعة المتجاوزة والمقاوَمة العابرة للحدود القومية/ الرقمية. بين أنواع التمتّع التي تتحدّى الحدود من ناحية، والكويرية والبهرجة والأرض ونضالات السكّان الأصليين ومناهضة الرأسمالية والتنظيم المناهض للاستعمار من ناحية أخرى.

حاول هذا العدد التقاط كيفية اتخاذ ممارسة الاحتشاد في المهرجان لأشكالٍ وتخيّلات متعدّدة. إلى جانب التعاون المباشر مع بعض الحالمات/ين والمتحدّثات/ين في المهرجان، دعَونا عدداً كبيراً من أصوات أخرى من الجنوب العالمي لنكون في نقاش جماعي حول الكثير من الثيمات والموضوعات المرتبطة بالجنوب. فيما يلي خريطة لبعض جلسات المهرجان التي كانت أكثر إلهامًا لنا.

Marta is a queer, transfeminist non-binary activist-researcher from ex-Yugoslavia, currently based in Barcelona. They work as a transnational movement organizer, a feminist economist and a weaver of systemic alternatives. They are the co-founder and one of the coordinators of the Global Tapestry of Alternatives, a global process that seeks to identify, document and connect alternatives on local, regional and global levels. Locally, they are engaged in anti-racist, transfeminist, queer, migrant organizing. They also hold a doctoral degree in Environmental Science and Technology from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, dedicated to decolonial feminist perspectives of a pluriverse of systemic alternatives and the creation of feminist alternative systems based on care and the sustainability of life. During their free time, they enjoy boxing, playing the guitar and the drums as part of a samba band, photography, hiking, cooking for loved ones and spoiling their two cats.

في الثاني من أيلول/ سبتمير 2021، التمّ شمل مجموعة رائعة من الناشطات النسويات والمناديات بالعدالة الاجتماعية ضمن فعاليات مهرجان (AWID Crear | Résister | Transform). لم يقتصر هدف اجتماعهنّ على مشاركة استراتيجيات المقاومة وعمليات الابتكار الخلّاقة المشتركة التي ترمي إلى تغيير العالم. لقد اجتمعت الناشطات ليتبادلن الغزَل الإباحي على «تويتر». قادت نانا سيكياما النشاط.

نانا من مؤسسي «مغامرات من مضاجع النساء الإفريقيات» وهي كاتبة «حيوات النساء الافريقيات الجنسيّة». لقد جمعت عملها مع عمل المنبر النسائيّ الكويري المنادي بالوحدة الإفريقية (AfroFemHub) للبحث في جواب السؤال التالي: ما هي الصياغات النسوية للرسائل النصّية ذات المحتوى الجنسي؟

أعتقد أن هذا سؤال مهمّ للغاية، لأنه يبحث في القضية الأكبر المتعلّقة بالمقاربة النسوية لكيفية تنقّل المرء في عالم الإنترنت. في ظل الرأسمالية، يمكن للخطاب المُنتَج حول الجسد والجنس، أن يكون مجرّدًا من الإنسانية ومُشوّهًا. كما أن مساحات المتعة الجنسية في الفضاء الافتراضي لها طابع آدائي مبتذل. لذا، فإن البحث عن طرق تُمكّننا من استكشاف رغباتنا باستحسان، يمكن أن تولّد مقاومة للسائد من نماذج العرض والاستهلاك. تباعًا، تُستعاد هذه المساحات كمواقع للتشابك الحَقّ، ويتبيّن أنّ الرسائل النصّية ذات المحتوى الجنسي لا بد وأن تكون نسويّة.

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن السماح للخطاب النسوي بتجسيد وجهه المرِح في فضاء الإنترنت، يساعد على مقارعة السردية الذائعة ومفادها أن التشابك في الفلك النسوي غير مرح وقاسٍ في طابعه العام. ولكن كما نعلم، فإن المتعة والمرح هي من صلب سياستنا وجزء متأصّل مما يعنيه أن يكون المرء نسويًا.

باستخدام وسم #SextLikeAFeminist، تقدَّم الناشطون والأكاديميون من حول العالم بـ»تويتات» تحمل نهمًا نسويًا كبيرًا. أورد لكم في هذا النص التويتات العشرة المفضّلة لدي.

يتبيّن من هذه التويتات الفكاهة المقرونة بالإثارة والاهتياج الجنسيّ، التي تتّسم بها المقاربة النسوية لكتابة الرسائل ذات المضامين الجنسية، دون أن تُسقط عن نفسها الالتزام بالمساواة والعدالة.

Elina es una joven feminista afrodominicana, que trabaja con enfoque interseccional. Es abogada de derechos humanos y está comprometida a usar su voz y sus capacidades para construir un mundo más justo, empático e inclusivo. Ingresó a la facultad de derecho a los 16 años, segura de que iba a obtener herramientas para entender y promover la justicia social. Luego de obtener el título de Juris Doctor [Doctora en Jurisprudencia] en la República Dominicana, cursó una maestría en Derecho Internacional Público y Derechos Humanos en el Reino Unido, como becaria Chevening. Fue la única mujer latinoamericana-caribeña en su clase y se graduó con honores.

Elina ha trabajado en la intersección de derechos humanos, género, migración y política en el gobierno, en colectivos de base y en organizaciones internacionales. Colaboró en el litigio de casos sobre violencia de género ante la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. Como integrante del Panel Consultivo de Jóvenes de UNFPA, contribuyó al fortalecimiento de los derechos sexuales y reproductivos en la República Dominicana. Fue una de las personas que lideraron la primera campaña de Amnistía Internacional sobre derechos de lxs trabajadorxs sexuales en las Américas, desarrollando una fuerte asociación con las organizaciones de trabajadorxs sexuales, y utilizando la posición de Amnistía para potenciar las voces de quienes defienden los derechos humanos de las mujeres y de lxs trabajadorxs sexuales. Elina es parte del Foro Feminista Magaly Pineda y la Global Shapers Community [Comunidad Global Shapers]. Habla español, francés e inglés.

Gracias a su diversificada trayectoria, Elina trae sólidas capacidades de gobernanza y de planificación estratégica, una experiencia sustancial en las Naciones Unidas y en mecanismos regionales de derechos humanos, además de su profunda determinación para que AWID siga siendo una organización inclusiva para todas las mujeres, especialmente, las feministas jóvenes y caribeñas. Con estas propuestas, se suma a una hermandad global de feministas fantásticas, desde donde podrá seguir cultivando su liderazgo feminista y nunca más se sentirá sola en su camino.