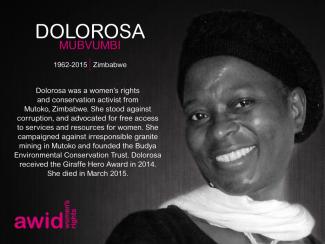

Dolorosa Mubvumbi

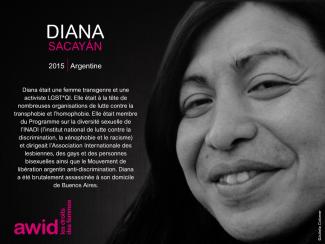

AWID’s Tribute is an art exhibition honouring feminists, women’s rights and social justice activists from around the world who are no longer with us.

This year’s tribute tells stories and shares narratives about those who co-created feminist realities, have offered visions of alternatives to systems and actors that oppress us, and have proposed new ways of organising, mobilising, fighting, working, living, and learning.

49 new portraits of feminists and Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRDs) are added to the gallery. While many of those we honour have passed away due to old age or illness, too many have been killed as a result of their work and who they are.

This increasing violence (by states, corporations, organized crime, unknown gunmen...) is not only aimed at individual activists but at our joint work and feminist realities.

The portraits of the 2020 edition are designed by award winning illustrator and animator, Louisa Bertman.

AWID would like to thank the families and organizations who shared their personal stories and contributed to this memorial. We join them in continuing the remarkable work of these activists and WHRDs and forging efforts to ensure justice is achieved in cases that remain in impunity.

“They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds.” - Mexican Proverb

It took shape with a physical exhibit of portraits and biographies of feminists and activists who passed away at AWID’s 12th International Forum, in Turkey. It now lives as an online gallery, updated every year.

To date, 467 feminists and WHRDs are featured.

El informe más reciente del Observatorio sobre la Universalidad de los Derechos desarma discursos como los de la «ideología de género», el «genocidio prenatal» y el «imperialismo cultural». También investiga los flujos de fondos para CitizenGo, la Alliance Defending Freedom/ADF Internacional y otros grupos anti-derechos. En este informe también se puede encontrar un análisis de los sistemas regionales de derechos humanos así como de las estrategias exitosas y los logros feministas.

Filter for funders that support initiatives in your geographical area.

Dear feminist movements,

Love is what keeps our feminist fire burning. Along with care for our communities, anger and rage in the face of injustice, and the courage to take action.

In September 2022, we stepped with great excitement into our leadership roles at AWID, as Co-Executive Directors. We felt the warmth and embrace of the feminist sisterhood as you welcomed us.

Reflecting on our most precious memories as feminists, we recall powerful moments of togetherness at street protests, sharp analysis, and brave voices shaking the status quo at gatherings. We held those intimate conversations into the night, laughed for hours, and danced at parties together.

Feminist fires need to be fed, especially in difficult times when there is no lack of external challenges, from the climate crisis and the rise of right-wing forces to exploitative economies and persisting patterns of oppression within our own social movements. It's these fires, burning ablaze everywhere, that light our ways and keep us warm, but we can’t disregard the exhausting effects of political violence and repression directed against many of our struggles, movements, and communities.

We understand the desire to change the world as an essential ingredient of feminist organizing. We can never forget that we are the ones we have been waiting for, in building alternatives and shaping our future. Yet, vibrant feminist energy cannot be taken for granted and must be safeguarded in many ways. In this, we will continue to be vigilant. Greater and equal access to care and wellbeing, to healing and pleasure, are not only instruments to prevent burnout and sustain our movements, though that is an important function; first and foremost, they are the way in which we hope to live our lives.

We are thrilled to roll up our sleeves and work with you. AWID’s new strategic plan “Fierce Feminisms: Together We Rise” reflects our conviction that now is the time for us to be fierce and unapologetic in our agendas while making an effort to connect across movements and truly get to know each other’s realities, so that we may rise together - because, for us, this is the only way.

Our plans include the long-awaited AWID Forum! We look forward to meeting you all in person and online in 2024. We are hearing from you the need to connect and recharge, to rest and heal, to be challenged and inspired, to share good food, and to laugh and dance together. Few things in this world are as powerful and transformative, as feminists from all parts of the world coming together, and we truly hold our breath for this moment, because we know the magic that we can create together.

Our membership engagement has taken on a life of its own through the AWID Community (our online platform for members), and our focus on building connection and solidarity resonates with many of you. Please join and connect with us and others in feminist movements around the world. We know the importance of connection in a time and space where the rules are not made for us, and we hold close our community, where each of us matters.

Together with our fantastic AWID colleagues, we promise to do our best to support feminist movements, as is the mission and purpose of AWID. Please hold us to account.

For the past 40 years, you - feminist movements - have shaped AWID’s history, and pushed us to be braver, creative, and radical. 40 is a fabulous age, and we look forward to another 40 years with you all. We are looking forward to the partnerships, calls to justice, collaboration, policy influencing, and badass feminist power that you all bring in navigating the ever-increasing backlash on gender, racial and environmental justice. We have so much to learn from you and from each other, as we collectively build the worlds we believe in.

Cindy Clark and Hakima Abbas, thank you for paving the way for us and preparing us to fill your enormous shoes. We always appreciate all those on whose shoulders we stood and continue to stand. We understand ourselves to be part of a broader movement landscape, feminist histories, presents, and daring futures.

AWID’s Board of Directors, we are grateful to you for the support and feminist love you show us, and for your commitment to Global South leadership and the co-leadership model. We send our love and respect to each and every AWID colleague, we feel honoured to be working with such an exceptional feminist team of dedicated professionals.

This is our first time writing a love letter together, how could we conclude it without expressing love, care, and respect for each other? It’s a pretty intense relationship we’ve stepped into! We both bring our different and diverse perspectives and skills to our work, and as individuals, we also bring our lived experiences and authentic selves.

Together with you all, we are a story in the making, a part of a beautiful woven - and often beautifully challenging - tapestry that continues into the future. We had fun starting this journey together with each other and with you, and we very much hope to keep the romance alive.

In solidarity, with love and care

Inna and Faye

21 February 2023, Member Mixer 5 on Feminist Politics with Faye and Inna.

Not a member yet? Find out more about AWID Membership.

We will reconnect with past partners, to ensure past efforts are honored. If your contact information has changed since the last Forum process, please update us so that we may reach you.

Suivez notre super-héroïne alors qu'elle se lance dans une quête pour récupérer le récit des acteurs anti-droits à travers le monde.

"Where is the money for feminist organizing?"

How much do you know about feminist resourcing? 📊 Take AWID's "Where is the Money for Feminist Organizing?" quiz to test your knowledge:

Take the quiz onlineDownload and print it

Nunca supe que tenía una familia cercana que me ama y que quiere que crezca. Mi mamá siempre ha estado presente para mí, pero nunca imaginé que tendría miles de familias por otros sitios, con las que no estoy relacionada por lazos de sangre.

Descubrí que la familia no son solo las personas relacionadas por lazos sanguíneos, sino la gente que te ama de forma incondicional, a quienes no les importa tu orientación sexual, ni tu estado de salud, ni tu estatus social, ni tu raza.

Al pensar en los momentos invaluables en que escuché a mis hermanas de todo el mundo que son firmes feministas –gente a quien no he conocido físicamente, pero quienes me apoyan, me enseñan, luchan por mí– me faltan las palabras: las palabras no pueden expresar cuánto las amo a ustedes, mis mentoras, y a las demás feministas. Ustedes son una madre, una hermana, una amiga para millones de chicas jóvenes.

Ustedes son maravillosas, ustedes luchan por personas a quienes no conocen –y eso es lo que las hace tan especiales–.

Mi corazón se alegra de expresar esto por escrito.

Las amo a todas y seguiré amándolas. Nunca he visto a ninguna de ustedes en forma física, pero parece que nos conociéramos desde hace décadas.

Somos feministas y estamos orgullosas de ser mujeres.

Vamos a seguir diciéndole al mundo que nuestra valentía es nuestra corona.

Una carta de amor de FAITH ONUH, una joven feminista de Nigeria

Para preguntas adicionales, por favor utiliza nuestro formulario de contacto. ¡Continuaremos actualizando este documento en base a las consultas que vayamos recibiendo de ustedes!

Avec Lindiwe Rasekoala, Lizzie Kiama, Jovana Drodevic et Malaka Grant.

Este nuevo informe revela las realidades de los recursos de las organizaciones feministas y por los derechos de las mujeres en una época de turbulencias políticas y económicas sin precedentes. A partir de un análisis de más de una década desde el último informe de AWID ¿Dónde está el dinero? (Regando las hojas, dejando morir las raíces), se hace un balance de las conquistas, las brechas y las amenazas crecientes en el panorama del financiamiento.

En el informe se celebra el poder las iniciativas de los movimientos para configurar la dotación de recursos en sus propios términos y, a la vez, se da la voz de alarma sobre los recortes masivos de las ayudas, el declive de la filantropía y el aumento de las reacciones adversas.

Se hace un llamado a los donantes para que inviertan copiosamente en las organizaciones feministas, pues estas son la infraestructura esencial para la justicia y la liberación. También se invita a los movimientos a reinventar modelos audaces y autodefinidos para una dotación de recursos fundada en el cuidado, la solidaridad y el poder colectivo.

Dans le monde entier et au sein des mouvements sociaux, les personnes désireuses d’innover ont tendance à se sentir seules et impuissantes face au « statu quo du mouvement ». Historiquement, les Forums de l’AWID ont joué un rôle dans le soutien de ces innovateur·trices en leur offrant une plateforme où leurs idées et pratiques sont accueillies et renforcées par les pensées et actions d’autres personnes de différentes régions et communautés qui les ont déjà explorées. Sara Abu Ghazal, féministe palestinienne au Liban, nous parle de ce qu’ont représenté les Forums pour toute une nouvelle génération de féministes de la région MENA (Moyen-Orient et Afrique du Nord) qui ont introduit de nouvelles façons de s’organiser, de nouvelles conceptions du féminisme et de nouvelles questions dans le paysage régional des droits des femmes.

New

As an online participant, you can facilitate activities, connect and converse with others, and experience first-hand the creativity, art and celebration of the AWID Forum. Participants connecting online will enjoy a rich and diverse program, from workshops and discussions to healing activities and musical performances. Some activities will focus on connection among online participants, and others will be truly hybrid, focusing on connection and interaction among online participants and those in Bangkok.

Feminists have long asserted that the personal is political. Crear, Resister, Transform Festival created spaces for feminists to discuss issues around body, gender and sexualities, and explored the interconnections of how these issues are both deeply embodied experiences, and simultaneously a terrain where rights are constantly disputed and at risk in society.

The power of feminist movements lie in how we organise and take coordinated action, not only amongst our own communities and movements, but with allied social justice causes and groups. This space provided opportunities for movements to share and strengthen organizing and tactical strategies with each other.

The COVID-19 global health pandemic has made the failures of neo-liberal capitalism even more apparent than ever before, exposed the cracks in our systems, and highlighted the need and opportunities to build new realities. A feminist economic and social recovery requires all of us to make it together. This journal edition in partnership with Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research, will explore feminist solutions, proposals and realities for transforming our current world, our bodies and our sexualities.

Explore the articles online or

Download PDF

La cumbre por el clima organizada por y para los movimientos.

📅 12 - 16 de noviembre de 2025

📍 Universidad Federal de Pará, Belém

Esta política rige para todas las páginas alojadas en https://www.awid.org/ y para cualquier otro sitio web bajo el control de AWID (el «Sitio web») y para las suscripciones a estos sitios. No se aplica a páginas alojadas por otras organizaciones distintas a AWID, hacia las cuales podemos dirigir un hipervínculo y cuyas políticas de privacidad pueden ser diferentes. Por favor, lee la siguiente política para que puedas comprender nuestra política de privacidad en cuanto a su naturaleza, propósito, uso y divulgación de tu información personal e identificable que es recogida a través de este sitio web.

En general, puedes navegar este sitio web sin enviarnos información personal. Sin embargo, en algunas circunstancias, te pediremos esa información personal.

Cuando te encuentras en el sitio web y se te pide información personal, estás compartiendo esa información sólo con AWID.

1.1.1 La información que nos das para recibir actualizaciones de AWID:

Cuando te registras para usar el sitio (por ejemplo, te suscribes para recibir correos electrónicos o para solicitar membresía) nos das la información necesaria acerca de ti, como tu nombre, país, idioma, para recibir actualizaciones por correo electrónico. Nos das esta información a través de formularios seguros y es almacenada en servidores seguros.

1.1.2 La información de pago que nos das para hacerte miembrx o para anotarte en algún evento:

Además, puede ser necesario que nos des información sobre el pago cuando te haces miembrx o cuando te anotas para eventos. AWID no almacena en sus servidores ninguna información relativa a tarjetas de crédito y usa portales seguros para procesar la información relativa a pagos.

1.1.3 La información opcional que decidiste darnos (con consentimiento)

Cuando te comunicas con AWID o nos das información opcional a través de formularios en el sitio web o utilizas el sitio para comunicarte con otrxs miembrxs, recogemos información sobre tu comunicación y cualquier otra información que elijas dar.

1.1.4 Información que nos das a través de los formularios de contacto o cuando te comunicas directamente con nosotrxs

Cuando te comunicas con nosotrxs, recogemos tu comunicación y toda otra información que decidas darnos.

Además, cuando interactúas con el Sitio web, nuestros servidores pueden llevar un registro de actividad que no te identifica personalmente («Información no personal»). Por lo general, recogemos las siguientes categorías de información no personal:

Para más información sobre las cookies, por favor consulta All about cookies.

Si no deseas recibir cookies puedes cambiar fácilmente tu navegador web para que rechace las cookies o notificarte cuando recibes una nueva cookie. Puedes mirar aquí cómo hacerlo.

AWID utiliza la información que recogemos acerca de ti para:

Si te has subscrito a los boletines electrónicos de AWID o a nuestras actualizaciones por correo electrónico o si te has hecho miembrx, te enviaremos comunicaciones regularmente en la forma especificada en el área correspondiente del sitio web. Puedes cancelar la suscripción de cualquiera de los boletines electrónicos o actualizaciones de correo electrónico en cualquier momento siguiendo los pasos indicados para ello en nuestros correos.

Es importante para AWID que tu información de identificación individual sea precisa. Siempre estamos buscando cómo hacer más fácil que puedas revisar y corregir la información que AWID tiene acerca de ti en nuestro sitio web. Si cambias tu dirección de correo electrónico, o si cualquier otra información que tengamos es incorrecta o desactualizada, por favor escríbenos a esta dirección.

Con excepción de lo explicado más abajo, AWID no revelará ninguna información personal acerca de ti que sea identificable, y no venderá ni alquilará a tercerxs listados conteniendo tu información. AWID podrá revelar información cuando tenga tu permiso para hacerlo o bajo circunstancias especiales, por ejemplo cuando crea de buena fe que la ley se lo exige.

De manera permanente implementamos y actualizamos las medidas administrativas, técnicas y de seguridad física para proteger tu información de accesos no autorizados, pérdida, destrucción o alteración. Algunas de las salvaguardas que usamos para proteger tu información son cortafuegos, encriptación de datos y controles de acceso a la información. Si sabes o tiene razones para creer que tus credenciales de membresía a AWID se han perdido, han sido robadas, malversadas o comprometidas de alguna forma o en caso de que sepas o sospeches de uso no autorizado de tu cuenta de membresía a AWID, por favor ponte en contacto con nosotrxs a través de nuestra página.

Esta política puede cambiar periódicamente. La política modificada será publicada en este sitio web y al final del texto se actualizará la fecha de Última actualización. Se enviará un correo electrónico con la actualización de la política revisada y si no estás de acuerdo con ella tendrás la opción de cancelar tu suscripción o suscripciones con nosotrxs. También puedes escribirnos aquí. ¡Agradecemos tus opiniones!

Última actualización: mayo de 2019

We welcome applications across the full range of thematic areas and intersections important to feminist and gender justice movements. In the application form, you will be able to mark more than one theme that fits your activity.