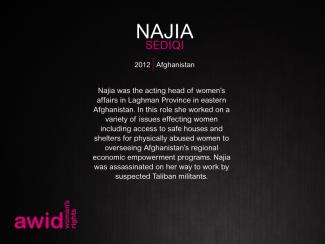

Nahia Sediqi

The “Where is the Money?” #WITM survey is now live! Dive in and share your experience with funding your organizing with feminists around the world.

Learn more and take the survey

Around the world, feminist, women’s rights, and allied movements are confronting power and reimagining a politics of liberation. The contributions that fuel this work come in many forms, from financial and political resources to daily acts of resistance and survival.

AWID’s Resourcing Feminist Movements (RFM) Initiative shines a light on the current funding ecosystem, which range from self-generated models of resourcing to more formal funding streams.

Through our research and analysis, we examine how funding practices can better serve our movements. We critically explore the contradictions in “funding” social transformation, especially in the face of increasing political repression, anti-rights agendas, and rising corporate power. Above all, we build collective strategies that support thriving, robust, and resilient movements.

Create and amplify alternatives: We amplify funding practices that center activists’ own priorities and engage a diverse range of funders and activists in crafting new, dynamic models for resourcing feminist movements, particularly in the context of closing civil society space.

Build knowledge: We explore, exchange, and strengthen knowledge about how movements are attracting, organizing, and using the resources they need to accomplish meaningful change.

Advocate: We work in partnerships, such as the Count Me In! Consortium, to influence funding agendas and open space for feminist movements to be in direct dialogue to shift power and money.

AWID, the Center for Women’s Global Leadership (CWGL), and the African Women's Development and Communication Network (FEMNET), offers this think piece to challenge mainstream understandings of development and put forward initial propositions for a feminist agenda for development, economic and gender justice.

Learn more about where this project comes from

These propositions are intended to be just that - proposals, to be discussed, debated, added to, taken apart, adapted, adopted, and even to inspire others.

COZINHA OCUPAÇÃO 9 DE JULHO

Our 2010 Annual Report highlights the major accomplishments of each of our strategic initiatives during the year.

Along with activity highlights, we include a brief analysis of the impact of our initiatives as well as reflections from our members and partners that further illustrate the relevance of AWID’s work and its connection to broader women’s rights movements.

This interactive document is complete with links to our websites and recent publications with in-depth information on the issues we address in the report.

Faye is a passionate Pan-African feminist, active in movements for women's rights, racial justice, migrant and labor rights, and environmental justice. Her activism builds on the legacy of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa and the aftermath of the apartheid era in Zimbabwe.

In 2019, Faye joined AWID as the Director of Finance, Operations and Development, and strived to ensure that AWID upholds the feminist principles and values in all of its operations. She brings over 20 years of experience in feminist leadership, strategy, and all aspects of finance and organizational development.

Faye is a committed Board Member of UAF-Africa and other women's rights organizations. She previously held a Head of Finance and Operations roles at Paediatric Adolescent Treatment for Africa and JASS - Just Associates Inc. in Southern Africa. She also held Directorship roles for International Computer Driving Licence (ICDL) in Central and Southern Africa. She holds a Bcompt in Accounting Science from University of South Africa and is a member of the Southern African Institute for Business Accountants.

Eni Lestari is an Indonesian domestic worker in Hong Kong and a migrant rights activist. After escaping her abusive employer, she transformed herself from a victim into an organizer for domestic workers in particular, and migrant workers in general. In 2000, she founded the Association of Indonesian Migrant Workers (ATKI-Hong Kong) which later expanded to Macau, Taiwan, and Indonesia. She was the coordinator and the one of the spokesperson of the Asia Migrants Coordinating Body (AMCB) - an alliance of grassroots migrants organisations in Hong Kong coming from Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, Nepal and Sri Lanka. She is also the current chairperson of International Migrants Alliance, the first-ever global alliance of grassroots migrants, immigrants, refugees, and other displaced people.

She has held important positions in various organizations including and current Regional Council member of Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development (APWLD), former Board Member of Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW), spokesperson for Network of Indonesian Migrant Workers (JBMI), advisor for ATKI-Hong Kong and Macau as well as the Association of Returned Migrants and Families in Indonesia (KABAR BUMI). She has been an active resource person in forums organized by academics, interfaith groups, civil societies, trade unions and many others at national, regional, and international arenas.

She has actively participated in United Nations assemblies/conferences on development and migrants’ rights and was chosen as a speaker at the opening of the UN General Assembly on Large Movement of Migrants and Refugees in 2016 in New York City, USA. She received nominations and awards such as Inspirational Women by BBC 100 Women, Public Hero Award by RCTI, Indonesian Club Award, and Non-Profit Leader of Women of Influence by American Chamber Hong Kong, and Changemaker of Cathay Pacific.

The main focus of our work is global. We also work closely with members and other women’s rights organizations and allies at the local, national and regional levels so that their realities inform our work.