Aysin Büyüknohutçu

Feminist Realities are the living, breathing examples of the just world we are co-creating. They exist now, in the many ways we live, struggle and build our lives.

Feminist Realities go beyond resisting oppressive systems to show us what a world without domination, exploitation and supremacy look like.

These are the narratives we want to unearth, share and amplify throughout this Feminist Realities journey.

Create and amplify alternatives: We co-create art and creative expressions that center and celebrate the hope, optimism, healing and radical imagination that feminist realities inspire.

Build knowledge: We document, demonstrate & disseminate methodologies that will help identify the feminist realities in our diverse communities.

Advance feminist agendas: We expand and deepen our collective thinking and organizing to advance just solutions and systems that embody feminist values and visions.

Mobilize solidarity actions: We engage feminist, women’s rights and gender justice movements and allies in sharing, exchanging and jointly creating feminist realities, narratives and proposals at the 14th AWID International Forum.

As much as we emphasize the process leading up to, and beyond, the four-day Forum, the event itself is an important part of where the magic happens, thanks to the unique energy and opportunity that comes with bringing people together.

Build the power of Feminist Realities, by naming, celebrating, amplifying and contributing to build momentum around experiences and propositions that shine light on what is possible and feed our collective imaginations

Replenish wells of hope and energy as much needed fuel for rights and justice activism and resilience

Strengthen connectivity, reciprocity and solidarity across the diversity of feminist movements and with other rights and justice-oriented movements

Learn more about the Forum process

We are sorry to announce that the 14th AWID International Forum is cancelled

Given the current world situation, our Board of Directors has taken the difficult decision to cancel Forum scheduled in 2021 in Taipei.

Dear Feminist Movements,

On behalf of the AWID Board of Directors, I am proud to introduce AWID’s next Co-Executive Directors: Faye Macheke and Inna Michaeli!

|

Faye Macheke is a passionate Pan-African feminist, active in movements for women's rights, racial justice, migrant and labor rights, and environmental justice. Her activism builds on the legacy of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa and the aftermath of the apartheid era in Zimbabwe. In 2019, Faye joined AWID as the Director of Finance, Operations and Development. She brings extensive experience in feminist leadership, strategy, and all aspects of organisational development. Faye is a committed Board Member of UAF-Africa and other women's rights organizations. She is based in Cape Town, South Africa. |

|

Inna Michaeli is a feminist lesbian queer activist and sociologist with many years of deep engagement in feminist and LGBTQI+ struggles, political education and organizing by and for migrant women, and Palestine liberation and solidarity. Inna joined AWID in 2016 and served in different roles, most recently as the Director of Programs. She brings extensive experience in research and knowledge building, policy advocacy and organizational development. Inna serves on the Board of the Jewish Voice for Peace - Germany. She is based in Berlin, Germany. |

This decision is the result of a rigorous process with full participation of the Board and the staff of AWID. The Board recognised and honoured the skills and talents of AWID staff by opening an internal hiring search. As a result, we had two brilliant candidates, who embody the integrity, ethic of care, and feminist intersectional values that drive AWID’s work, apply together as a team. Faye and Inna brought forward a brave and exciting vision to meet the challenges of this moment: building a global feminist community, resisting and disrupting systems of oppression, and supporting feminist movements to thrive.

As AWID celebrates 40 years we are excited for Inna and Faye to co-lead AWID into our next strategy and a new phase of evolving, pushing boundaries, and supporting feminist movements worldwide.

Appointing and supporting AWID’s Co-Executive Directors to lead the organisation is a fiduciary responsibility we take seriously as a Board. How we engage those processes is also a reflection of AWID’s brilliant and diverse membership, which elects AWID’s Board.

As we say good-bye to Cindy and Hakima, we, the Board, unanimously and enthusiastically welcome Faye and Inna as our next Co-EDs as of September 5, 2022. Stay tuned for more updates about our leadership transition in the months ahead.

Most of all, thank you for your ongoing support!

In feminist solidarity and love,

Margo Okazawa-Rey

President, AWID Board

We welcome applications across the full range of thematic areas and intersections important to feminist and gender justice movements. In the application form, you will be able to mark more than one theme that fits your activity.

AWID is a part of an incredible ecosystem of feminist movements working to achieve gender justice and social justice worldwide. With our 40th anniversary, we are celebrating all that we’ve built over these last 40 years. As a global feminist movement support organization we know that working with fierce feminisms is our way forward, acknowledging both the multiplicity of feminisms and the value of fierce and unapologetic drive for justice. The state of the world and of feminist movements calls for brave conversations and action. We look forward to working together with our members, partners and funders in creating the worlds we believe in, celebrating the wins and speaking truth to power in service of feminist movements globally.

The 2023 Feminist Calendar is our gift to movements. It features the artwork of some of our amazing AWID members.

Get it in your preferred language! |

Select image quality |

| English | Print Quality | Digital Version |

| Français | Print Quality | Digital Version |

| Español | Print Quality | Digital Version |

| Português | Print Quality | Digital Version |

| عربي | Print Quality | Digital Version |

| Русский | Print Quality | Digital Version |

.

ใหม่

ผู้เข้าร่วมประชุมจะได้เข้าร่วมตามสถานที่ต่างๆนอกเพื้นที่ในการจัดงานที่กรุงเทพฯ และตามส่วนต่างๆของ โลกในแต่ละวันของการประชุม สถานที่ประชุมที่ผู้เข้าร่วมจัดการเองทั้งหมดนั้นจะเชื่อมต่อกับสถานที่จัดงาน

จริงในกรุงเทพฯเช่นเดียวกับบุคคลที่เชื่อมต่อทางออนไลน์ ผู้เข้าร่วมในจุดศูนย์กลาง Hub นี้จะสามารถ ดำเนินรายการในหัวข้อกิจกรรมต่างๆ เข้าร่วมอภิปราย แลกเปลี่ยน และเพลิดเพลินไปกับโปรแกรม ที่หลากหลาย

ที่ตั้งจุดศูนย์กลาง Hub จะประกาศในปี 2567

Thank you for your interest, but the page you're looking for no longer exists.

You can explore more content and updates at https://www.awid.org.

Razan was a 21-year-old volunteer medic in Palestine.

She was shot as she ran toward a fortified border fence, in an effort to reach a casualty in the east of the south Gaza city of Khan Younis.

In her very last Facebook post, Razan said: “I am returning and not retreating,” adding: “Hit me with your bullets. I am not afraid.”

Most of María’s life was devoted to incorporating a feminist and gender perspective in institutional and organizational work, and capacity building in Latin America.

As a child, María had a strong interest in art, communication, nature, literature, and the achievement of justice, especially for women and marginalized groups.

María was committed to sexual and reproductive rights and was a member of the National Board for Integral Education in Sexuality. She is remembered by those who loved her as a “passionate and restless fighter” with a strong commitment to women’s and children’s rights.

Yes please. The world has changed since 2021 and we invite you to submit an activity that reflects your current realities and priorities.

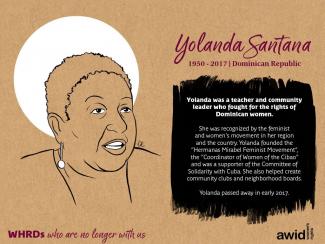

Dora was born in Benue State, Nigeria. She was a globally acclaimed pharmacist, technocrat, erudite scholar and community leader.

Dora’s revolutionary work created a paradigm shift in the Nigerian public service when she served as Director General of National Agency for Food and Drugs Administration and Control (NAFDAC) from 2001-2008. She spearheaded reforms in policy and regulatory enforcement that radically reduced the measure of fake drugs that plagued the Nigerian pharmaceutical sector during her tenure.

Having exemplified the reality of a courageous, competent woman who challenged the ills of a dominantly patriarchal society and drove change, she became an icon for women’s empowerment. She was appointed the Minister of Information and Communication between 2008 and 2010.

She died after a battle with cancer and is survived by her husband, six children and three grandchildren.

لغات العمل في جمعية حقوق المرأة في التنمية هي الإنجليزية والفرنسية والإسبانية. ستتم إضافة اللغة التايلاندية كلغة محلية، بالإضافة إلى لغة الإشارة وإجراءات الاتصال الأخرى. يمكن إضافة لغات أخرى إذا سمح التمويل بذلك، لذا تحقق/ي مرة أخرى بانتظام للحصول على التحديثات. نحن نهتم بالعدالة اللغوية وسنحاول تضمين أكبر عدد ممكن من اللغات بقدر ما تسمح به مواردنا. نأمل في خلق فرص متعددة للكثيرين/ات منا للتواجد بلغاتنا والتواصل مع بعضنا البعض.

"She was not a person. She was a power."

- a fellow activist remembering Navleen Kumar

With commitment and integrity, she worked for more than a decade to protect and restore the lands of Indigenous people (adivasi) in Thane district, an area taken away by property and land developers using such means as coercion and intimidation. She fought this injustice and crime through legal interventions at different courts, realizing that manipulation of land records was a recurrent feature in most cases of land acquisition. In one of the cases, that of the Wartha (a tribal family), Navleen found out that the family had been cheated with the complicity of government officials.

Through her work, she helped restore the land back to the Wartha family and continued to pursue other cases of adivasi land transfers.

“Her paper on the impact of land alienation on adivasi women and children traces the history and complexities of tribal alienation from the 1970s, when middle class families began to move to the extended suburbs of Mumbai as the real estate value in the city spiralled.

Housing complexes mushroomed in these suburbs, and the illiterate tribals paid the price for this. Prime land near the railway lines fetched a high price and builders swooped down on this belt like vultures, to grab land from tribals and other local residents by illegal means.”

-Jaya Menon, Justice and Peace Commission

During the course of her activism, Navleen received numerous threats and survived several attempts on her life. Despite these, she continued working on what was not only important to her but contributed to changing the lives and realities of many she supported in the struggle for social justice.

Navleen was stabbed to death on 19 June 2002 in her apartment building. Two local gangsters were arrested for her murder.

يرجى حساب تكاليف السفر إلى بانكوك، والإقامة والبدل اليومي، والتأشيرة، وأي احتياجات خاصة بإمكانية الوصول، والنفقات الطارئة، بالإضافة إلى رسوم التسجيل التي سيتم الإعلان عنها قريبًا. تتراوح أسعار الفنادق في منطقة سوكومفيت في بانكوك ما بين 50 دولارًا أمريكيًا إلى 200 دولار أمريكي في الليلة الواحدة في حالة حجز غرفة مزدوجة.

يحصل أعضاء جمعية حقوق المرأة في التنمية على خصم عند التسجيل، لذلك إذا لم تكن عضوًا/ة بعد، فإننا ندعوك إلى التفكير في أن تصبح عضوًا/ة والانضمام إلى مجتمعنا النسوي العالمي.

Diana Isabel Hernández Juárez was a Guatemalan teacher, human rights defender and environmental and community activist. She was the coordinator of the environmental program at Our Lady of Guadalupe Parish on the South coast of the country.

Diana dedicated her life to co-creating environmental awareness, working especially closely with local communities to address environmental issues and protect natural resources. She initiated projects such as forest nurseries, municipal farms, family gardens and clean-up campaigns. She was active in reforestation programmes, trying to recover native species and address water shortages, in more than 32 rural communities.

On 7 September 2019, Diana was shot and killed by two unknown gunmen while she was participating in a procession in her hometown. Diana was only 35 years old at the time of her death.

لقد كان منتدى جمعية حقوق المرأة في التنمية دائمًا مساحة لا تخجل من النقاشات الصعبة والمطلوبة بشدة. نحن نرحب بهذه المشاركات عندما يتمكن المنظمون/ات بعناية من توفير الاحترام والأمان في المساحة للمشاركين/ات.

Mirna Teresa Suazo Martínez was part of the Garifuna (Afro-descendent and Indigenous) Masca community, living on the North Caribbean coast of Honduras. She was a community leader and a fervent defender of the Indigenous territory, a land that was violated when the National Agrarian Institute of Honduras gave territorial licenses to people outside of the community.

This deplorable deed resulted in repeated harassment, abuse and violence against the Masca, where economic interests of different groups met those of Honduran armed forces and authorities. According to the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras (OFRANEH), the strategy of these groups is to evict and exterminate the Indigenous population.

“Masca, the Garifuna community located next to the Cuyamel Valley, is part of the area of influence of one of the supposed model cities, a situation that has triggered territorial pressures along the Garifuna coast.” - OFRANEH, 8 September 2019

Mirna Teresa, president of the Board of Trustees of the Masca Community in Omoa, was also firmly rejecting the construction of two hydroelectric plants on the river that carries the same name as her community, Masca.

“The Garífuna community attributes the worsening of the situation in their region to their opposition to tourist exploitation, the monoculture of African palm and drug trafficking, at the same time that it seeks to build an alternative life through the cultivation of coconut and other products for self-consumption.” - Voces Feministas, 10 September 2019

Mirna Teresa was murdered on 8 September 2019 in her Restaurant “Champa los Gemelos”.

She was one of six Garifuna women defenders murdered between September and October 2019 alone. According to OFRANEH, there was no investigation by the authorities into these crimes.

“In the case of the Garífuna communities, a large part of the homicides are related to land tenure and land management. However, squabbles between organized crime have resulted in murders, such as the recent ones in Santa Rosa de Aguán.” - OFRANEH, 8 September 2019

نحن ندرك تمامًا العقبات العملية والضغوط العاطفية المرتبطة بالسفر الدولي، وخاصة من الجنوب العالمي. تعمل جمعية حقوق المرأة في التنمية مع TCEB (مكتب تايلاند للمؤتمرات والمعارض) لدعم المشاركين/ات في المنتدى في الحصول على التأشيرات. سيتم توفير المزيد من المعلومات حول هذه المساعدة للحصول على التأشيرة عند التسجيل، بما في ذلك معلومات الاتصال الخاصة بمكان وكيفية التقديم.