Twenty years of resistance and essential work in Haiti

Sometime in 1970, before the death of Haitian President François Duvalier, his paramilitaries stormed, ransacked, and occupied the Port-au-Prince headquarters of La Ligue Feminine d’Action Sociale (The Women’s League for Social Action, LFAS), Haiti’s first women’s rights organization, created in 1934. Moments later, the Ligue’s organizers ran to the site and rescued their archives, which had been dumped on the street. The women dusted off and carried the records back home with them, presumably to rebuild on the feminist work that had been almost scattered.[1]

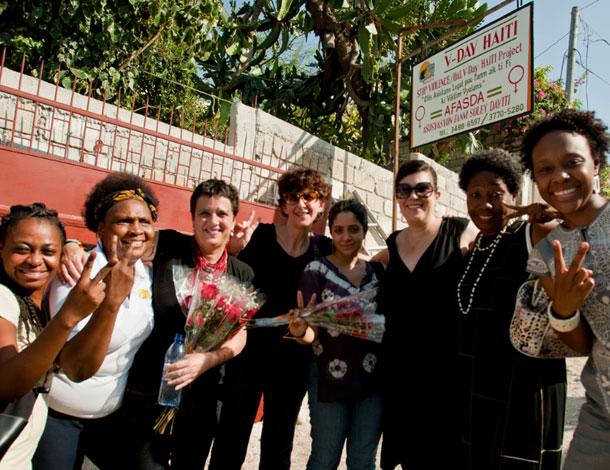

Twenty-seven years later, after the 1997 coup d’état in Haïti, a group of feminist educators and lawyers started a conversation. They cut through masculinist national concerns around contested elections and state-building in order to discuss the widespread and intersecting issue of gender-based violence in the country. So started Asosyasyon Fanm Soley Dayiti (AFASDA) (“Sun Women’s Association of Haiti”), an action network whose mission was to fill a gap to address violence against women.

Since then, AFASDA has collaborated with a number of partners to lay down groundwork--including services, campaigns, women’s rights trainings, legal aid, and leadership trainings to support women survivors of violence, in a context where 27% of Haitian women report having experienced physical violence by their husband or another person by the age of 15.

Created as a form of resistance, AFASDA’s mission is to work with Haitian women and girls to advance their overall development, the respect of their rights, and also to contribute to reframing violence against women from a domestic problem to a national one.[2]

The organisation, an AWID member since 2016, has collaborated in an extensive women’s mobilization campaign, and also coordinated a program promoting national dialogue in partnership with community radio stations.

Celebrating their 20th anniversary, strengthened by experience and strategic alliances, the organization pursues its mission and sees new opportunities for women to exercise their full potential and to meaningfully contribute to the rebuilding the country.

“For example, our most recent success has been the investigation and prosecution of a police officer who sexually assaulted a young student, with a new law that was just passed,” says Elvire Eugène, Executive Director of AFASDA and Cap-Haïtien resident, a city in northern Haiti.

At the national level, AFASDA is a founding member of the National Coordination for Advocacy on Women's Rights (CONAP) and the Nap Vanse platform. The latter is a member of the National Consultations on Women Victims of Violence, a founder of REFAGNO (Far North Women’s Network).

AFASDA has more than 18 branches across the country, as well as local committees and nearly 3,000 members (composed of women, girls and youth) who participate in decision-making and direction of the work as part of a general assembly.

The organisation is part of the frontline in the fight against gender-based violence (psycho-legal support, awareness raising, etc.). To contribute to the decrease in gender-based violence cases, AFASDA offers legal support to victims, provides temporary housing, organizes discussion and debate seminars and awareness raising activities for the general public.

“Our work alongside partners contributes to the prevention of violence against women and girls and social reintegration through public awareness raising on violence against women and girls and to legal authorities and other key actors on the difficulties in caring for women victims of violence.” The organization provides women victims of violence with suitable care and facilitates access to appropriate services.

“We’re also activists, that is to say, we have a responsibility to go into other neighbourhoods to talk about violence. Sometimes we assume people know what violence is but we later realize there are several neighbourhoods where people don’t know what ite is. It’s up to us to go find them and talk to them about violence."

"Because in the office we receive a lot of cases proving that people don’t know what violence is. Sometimes they face it but don’t know where to go. AFASDA represents a point of reference.”

“That is to say, we’re there to help, to help them recuperate and if there is a misunderstanding with their partner, we have a duty to call the partner too. We send him a letter and when both return to the office, we mediate between the woman and the partner. After repeated visits it’s up to them to hold back.”

The Haitian contingent at the Black Feminisms Forum and the 2016 AWID International Forum consisted of several AFASDA members, including Cathy Elvariste and Myriam Dubuisson, who led a session titled “Toward a Strong Coalition of Women’s Organizations at the Francophone Caribbean Country Level”.

“The last AWID Forum created new openings and opportunities for us and introduced us to activists from different countries.”

Elvariste and Dubuisson engaged with other feminists from across Africa and the diaspora, creating a transnational pivot to complement their work at home.

“We hope that the follow-up to the Forum will be effective, that certain actions will be taken and that all countries around the world will engage in the fight for substantive respect for women’s rights.”

[1] For a loving and comprehensive narration on the Haitian women’s movement, see: Sanders, Grace Louise. “La voix des femmes: Haitian Women’s Rights, National Politics and Black Activism in Port-au-Prince and Montreal: 1934-1986”. 2013.

[2] For a perspective on the state of Haitian feminist organizing to end violence against women in the last 25 years, see: Louis, Eunide. “Violences faites aux femmes en Haïti : État des lieux et perspectives”. Haiti Perspectives. Vol. 2. no. 3. Automne 2013.