Hanifa Safi

El Tributo de AWID es una exhibición de arte que honra a feministas, a activistas por los derechos de las mujeres y de la justicia social de todo el mundo que ya no están con nosotrxs.

El Tributo de este año cuenta y comparte las historias y narraciones de quienes crearon conjuntamente realidades feministas, ofrecieron visiones de alternativas a los sistemas y actores que nos oprimen, y propusieron nuevas formas de organizarnos, de movilizarnos, de luchar, de trabajar, de vivir y de aprender.

Se agregan a la galería 49 retratos nuevos de feministas y defensorxs de derechos humanos. Aunque muchxs feministas y defensorxs han fallecido debido a edad avanzada o enfermedad, muchísimxs han sido asesinadxs debido a su trabajo y por ser quienes eran.

Esta violencia creciente (de parte de Estados, empresas transnacionales, crimen organizado, sicarios no identificados, etc.) no se dirige solo a activistas individuales sino a nuestro trabajo común y a las realidades feministas.

Visita nuestra exhibición en línea

Lors retratos de 2020 fueron diseñados por la ilustradora y animadora galardonada, Louisa Bertman.

En AWID nos gustaría agradecer a las familias y organizaciones que nos compartieron sus historias personales, y así haber contribuido a este memorial. Nos unimos a ellxs para continuar el extraordinario trabajo de estxs activistas y defensorxs, y en el esfuerzo para asegurarnos de que se logre justicia en los casos que permanecen en la impunidad

"Ellos trataron de enterrarnos pero no sabían que éramos semillas."‐ Proverbio Mexicano

Primero tomó forma como una exposición física de retratos y biografías de feministas y activistas que habían fallecido, en el 12º Foro Internacional de AWID, en Turquía. Ahora vive como una galería en línea, que actualizamos cada año.

Desde 2012 hemos presentado más de 467 feministas y defensorxs.

L'économie solidaire (qui inclut l'économie coopérative et l’économie du don) est un cadre alternatif qui adopte différentes formes dans divers contextes et qui est ouvert au changement continuel.

Dans une économie solidaire, les producteurs mettent en place des processus économiques qui sont intimement liés à leurs réalités, à la préservation de l'environnement et à la coopération mutuelle.

Selon la géographe féministe Yvonne Underhill-Sem, l'économie du don est un système économique dans lequel les biens et les services circulent entre les personnes sans accord explicite de leur valeur, ou sans impliquer de réciprocité ultérieure.

Derrière le don il y a la relation humaine, la bienveillance et l'attention portée à la nurturance* de toute la société, non seulement limitée à soi-même et aux proches. Il s’agit ici de la notion du collectif.

Par exemple, dans la région du Pacifique, cette approche comprend la collecte, la préparation et le tissage de ressources terrestres et marines pour fabriquer des tapis, des ventilateurs, des guirlandes et des objets de cérémonie. Elle comprend également l'élevage du bétail et le stockage des récoltes saisonnières.

Pour les femmes, les incitations à s’engager dans des activités économiques sont diverses et multiples, allant de la réalisation d’aspirations de carrière afin de gagner de l'argent pour une vie confortable à long terme, à gagner de l'argent pour joindre les deux bouts, à rembourser une dette ou encore à échapper aux corvées de la vie courante.

Pour s’adapter aux divers environnements au sein desquels les femmes travaillent, le concept d'économie solidaire est en développement permanent et est continuellement discuté et débattu.

Nurturance : Nourriture et soins émotionnels et physiques donnés à quelqu'un.

На данный момент опрос в KOBO доступен на арабском, английском, французском, португальском, русском и испанском языках. В начале опроса у вас будет возможность выбрать нужный вам язык.

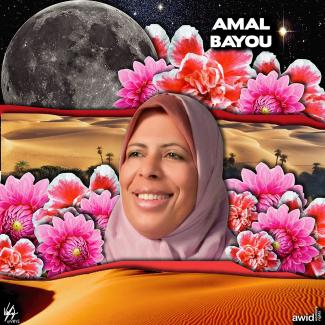

Amal fue una destacada política y parlamentaria de Libia.

Fue docente de la Universidad de Benghazi desde 1995 hasta su muerte, en 2017. Amal fue activista de la sociedad civil e integrante de varias iniciativas sociales y políticas. Asistió a las familias de lxs mártires y de lxs desaparecidxs y fue una de lxs fundadorxs de una iniciativa juvenil llamada «Juventud de Benghazi Libia».

En las elecciones parlamentarias de 2014, Amal fue elegida para la Cámara de Representantes con más de 14.000 votos (el mayor número de votos recibido por unx candidatx en las elecciones de 2014). Permanecerá en la memoria de muchxs como una mujer que actuó en política para garantizar un futuro mejor en uno de los contextos de la región más difíciles y afectados por los conflictos.

An economic system in which production and consumption patterns are based on profit using privately owned capital goods and wage labour. The system builds on individual wealth and capital accumulation at the lowest cost to the investor, with little regard for the societal costs and exploitation of the workforce - both paid and unpaid.

The conversion of land and activities related to it (like agriculture) into commodities that can be bought or sold for profit.

Institutions (like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, or regional development banks) that provide loans to countries lacking sufficient money to cover funding shortfalls or to finance development projects. Historically, the lending policies of these institutions have been determined by economically powerful Western countries and private enterprises. Loans to low-income countries in particular typically include conditionalities that prompt economic reforms in these countries to support neo-liberalism.

A set of economic and political theories in which market forces, rather than governments, determine key aspects of the economy with governments acting to support globalized markets and the interests of capital. Neo-liberal economic policies typically include promotion of free trade, privatisation, reduced government spending on social programs, subsidies and tax exemptions for business, deregulation of financial sector and foreign investments, low taxes on the wealthy and corporations, flexible labour and weak environmental protection.

Refers to systemic and institutionalized male domination embedded in and perpetuated by cultural, political, economic and social structures and ideologies. Hetero-patriarchy in addition, is a patriarchal system that is also based on the belief that heterosexuality is the only normal and acceptable sexual orientation.

Tendo em conta que o inquérito WITM foca-se nas realidades do financiamento de organizações feministas, a maioria das perguntas aborda o tópico do financiamento do seu grupo entre 2021-2023. Será preciso ter essas informações facilmente acessíveis para preencher o inquérito (por exemplo, os seus orçamentos anuais e as principais fontes de financiamento).

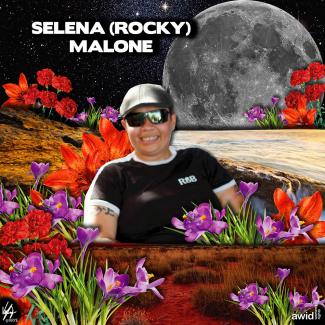

Engagée auprès de jeunes lesbiennes, gays, bisexuels, transgenres, intersexuels, queers, et transgenres (appelés Brotherboys-BB et Sistergirls-SS dans la communauté aborigène en Australie), Rocky faisait preuve de vision et d'un leadership inspirants.

Rocky avait commencé sa carrière auprès de la police du Queensland en tant qu'agent de liaison. Faire une différence était très important pour elle. Elle a mené un travail de soutien impressionnant auprès de jeunes de cette communauté en tant que responsable du service jeunesse « Open Doors » (portes ouvertes). Rocky a œuvré dans des situations complexes liées spécifiquement aux questions de genre et d'identité sexuelle.Elle avait un don naturel dans ce domaine: c’était une leader communautaire solide, une femme sereine, une amie fidèle, une personne aimante et attentionnée ainsi qu’une actrice du changement. Rocky était membre fondatrice d’IndigiLez Leadership and Support Group.

En 2016, à la Cour suprême de Brisbane, l'ancien juge de la Haute Cour, Michael Kirby, a cité le nom de Rocky lorsqu'il a loué le travail du service juridique de la communauté LGBTI au fil des années. Rocky s'est engagée très fermement en faveur des droits humains de la communauté « LGBTIQBBSG », elle a repoussé les limites et induits des changements de manière respectueuse et aimante.

We are witnessing an unprecedented level of engagement of anti-rights actors in international human rights spaces. To bolster their impact and amplify their voices, anti-rights actors increasingly engage in tactical alliance building across sectors, regional and national borders, and faiths.

This “unholy alliance” of traditionalist actors from Catholic, Evangelical, Mormon, Russian Orthodox and Muslim faith backgrounds have found common cause in a number of shared talking points and advocacy efforts attempting to push back against feminist and sexual rights gains at the international level.

Key activities: As the government of the Roman Catholic Church, the “Holy See” uses its unique status as Permanent Observer state at the UN to lobby for conservative, patriarchal, and heteronormative notions of womanhood, gender identities and “the family”, and to propagate policies that are anti-abortion and -contraception

Based in: Vatican City, Rome, Italy.

Religious affiliations: Catholic

Connections to other anti-rights actors: US Christian Right groups; interfaith orthodox alliances; Catholic CSOs

Key activities: Self-described as the “collective voice of the Muslim world”, the OIC acts as a bloc of states in UN spaces. The OIC attempts to create loopholes in human rights protection through references to religion, culture, or national sovereignty; propagates the concept of the “traditional family”; and contributes to a parallel but restrictive human rights regime (e.g. the 1990 Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam).

Based in: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Religious affiliations: Muslim

Connections to other anti-rights actors: Ultra conservative State missions to the UN, such as Russia

Key activities: International and regional conferences; research and knowledge-production and dissemination; lobbying at the United Nations “to defend life, faith and family”

Based in: Rockford, Illinois, U.S.

Religious affiliation: Predominantly Catholic and Christian Evangelical

Connections to other anti-rights actors: Sutherland Institute, a conservative think-tank; the Church of Latter-Day Saints; the Russian Orthodox Church’s Department of Family and Life; the anti-abortion Catholic Priests for Life; the Foundation for African Culture and Heritage; the Polish Federation of Pro-Life Movements; the European Federation of Catholic Family Associations; the UN NGO Committee on the Family; and the Political Network for Values; the Georgian Demographic Society; parliamentarians from Poland and Moldova, etc; FamilyPolicy; the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies; and HatzeOir; C-Fam; among others

Key activities: Lobbying at the United Nations, particularly the Commission of the Status of Women to “defend life and family”; media and information-dissemination (Friday Fax newsletter); movement building; trainings for conservative activists

Based in: New York and Washington D.C., U.S.

Religious affiliations: Catholic

Connections to other anti-rights actors: International Youth Coalition; World Youth Alliance; Human Life International; the Holy See; coordinates the Civil Society for the Family; the Family Research Council (U.S.) and other Christian/Catholic anti-rights CSOs; United States CSW delegation

Key activities: Lobbying in international human rights spaces for “the family” and anti-LGBTQ and anti-CSE policies; training of civil society and state delegates (for example, ‘The Resource Guide to UN Consensus Language on Family Issues’); information dissemination; knowledge production and analysis; online campaigns

Based in: Gilbert, Arizona, U.S.

Religious affiliations: Mormon

Connections to other anti-rights actors: leader of the UN Family Rights Caucus; C-Fam; Jews Offering New Alternatives to Homosexuality (JONAH); the National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH); World Congress of Families; CitizenGo; Magdalen Institute; Asociación La Familia Importa; Group of Friends of the Family (25 state bloc)

Key activities: Advocacy in international policy spaces including the United Nations, the European Union, and the Organization of American States for “the family”, against sexual and reproductive rights; training youth members in the use of diplomacy and negotiation, international relations, grassroots activities and message development; internship program to encourage youth participation in its work; regular Emerging Leaders Conference; knowledge production and dissemination

Based in: New York City (U.S.) with regional chapter offices in Nairobi (Kenya), Quezon City (The Philippines), Brussels (Belgium), Mexico City (Mexico), and Beirut (Lebanon)

Religious affiliations: primarily Catholic but aims for interfaith membership

Connections to other anti-rights actors: C-Fam; Human Life International; the Holy See; Campaign Life coalition

Key Activities: The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC), capitalizing on its close links to the Russian state, has operated as a “norm entrepreneur” in human rights debates. Russia and the ROC have co-opted rights language to push for a focus on “morality” and “traditional values” as supposed key sources of human rights. Russia led a series of “traditional values” resolutions at the Human Rights Council and has been at the forefront of putting forward hostile amendments to progressive resolutions in areas including maternal mortality, protection of civil society space, and the right to peaceful protest.

Connections to other anti-rights actors: Organization of Islamic Cooperation; Eastern European and Caucasus Orthodox churches, e.g. Georgian Orthodox Church; U.S. Christian Right including U.S. Evangelicals; World Congress of Families; Group of Friends of the Family (state bloc)

Te presentamos el Sindicato Red de Solidaridad, un sindicato de servicios y salud liderado en su mayoría por mujeres. Surgiendo como respuesta a la creciente precariedad, salarios insuficientes y entornos laborales hostiles que enfrentan diariamente lxs trabajadorxs en Georgia, el Sindicato Red de Solidaridad lucha por lugares y condiciones de trabajo dignos.

¿Su objetivo? Crear un movimiento obrero democrático nacional. Para hacerlo, se ha asociado con otros sindicatos locales y regionales y ha creado lentamente una red de sindicatos, empoderando por el camino a cada vez más trabajadoras para que se conviertan en líderes sindicales.

Su enfoque político es holístico. Para el Sindicato Red de Solidaridad, los temas de derechos laborales están directamente conectados con agendas y reformas políticas y económicas nacionales más amplias. Por eso están presionando por la justicia fiscal, los derechos de las mujeres y personas LGBTQIA+, y luchando contra el desmantelamiento del estado de bienestar georgiano.

Solidarity Network también forma parte de Huelga Social Transnacional (Transnational Social Strike, TSS), una plataforma política e infraestructura inspirada en la organización de migrantes, mujeres y trabajadores esenciales que trabaja para construir conexiones entre los movimientos laborales a través de las fronteras y fomentar la solidaridad global.

أكيد. سيتم محي اجوبتك بعد عملية معالجة المعطيات وتحليلها وسيتم استعمالها لأهداف بحثية فقط. لن تتم أبداً مشاركة المعطيات خارج AWID وسيتم معالجتها فقط عن طريق طاقم AWID والمستشارات/ين اللواتي/ اللذين يعملن/وا في مشروع "أين المال" معنا. خصوصيتكم/ن وسرّيتكم/ن هي في أعلى سلم أولوياتنا. سياسة الخصوصية متواجدة هنا.

Zita was a women’s rights activist who defended the rights of rural women in Greater Kivu.

She was the first Executive Director of UWAKI - a well known women’s organisation. Through her work with Women's Network for Rights and Peace (RFDP), and the Women's Caucus of South Kivu for Peace, she committed her life to helping to restore peace in the Eastern DRC. She spoke out strongly against the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war.

In 2006, she put herself forward as a candidate in the first democratic elections in the DRC. Although she did not win, she continued to advocate for women’s rights and the South Kivu community remembers her fondly.