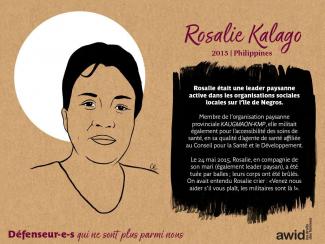

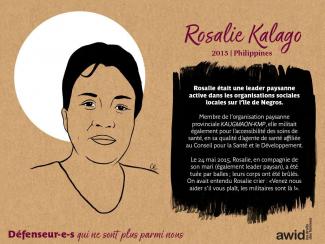

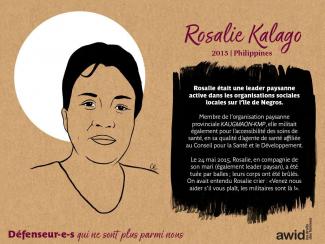

Rosalie Kalago

Young feminist activists play a critical role in women’s rights organizations and movements worldwide by bringing up new issues that feminists face today. Their strength, creativity and adaptability are vital to the sustainability of feminist organizing.

At the same time, they face specific impediments to their activism such as limited access to funding and support, lack of capacity-building opportunities, and a significant increase of attacks on young women human rights defenders. This creates a lack of visibility that makes more difficult their inclusion and effective participation within women’s rights movements.

AWID’s young feminist activism program was created to make sure the voices of young women are heard and reflected in feminist discourse. We want to ensure that young feminists have better access to funding, capacity-building opportunities and international processes. In addition to supporting young feminists directly, we are also working with women’s rights activists of all ages on practical models and strategies for effective multigenerational organizing.

We want young feminist activists to play a role in decision-making affecting their rights by:

Fostering community and sharing information through the Young Feminist Wire. Recognizing the importance of online media for the work of young feminists, our team launched the Young Feminist Wire in May 2010 to share information, build capacity through online webinars and e-discussions, and encourage community building.

Researching and building knowledge on young feminist activism, to increase the visibility and impact of young feminist activism within and across women’s rights movements and other key actors such as donors.

Promoting more effective multigenerational organizing, exploring better ways to work together.

Supporting young feminists to engage in global development processes such as those within the United Nations

Collaboration across all of AWID’s priority areas, including the Forum, to ensure young feminists’ key contributions, perspectives, needs and activism are reflected in debates, policies and programs affecting them.

Des mots perdus |

|

|

| Chinelo Onwualu | Ghiwa Sayegh |

« Lorsque nous avons désespérément besoin de changement, comme c’est le cas dans la maladie et l’insurrection, notre langage se vide de sa complexité et se réduit à l’essentiel... Mais à mesure que la maladie et la révolution persistent, le langage fabriqué en elles et à leur sujet s’approfondit, laisse entrer plus de nuances, absorbé par l’expérience profondément humaine qu’est de rencontrer de ses propres limites sur le site de la fin du monde. »

Johanna Hedva

Lorsque nous avons commencé à imaginer un tel numéro avec Nana Darkoa, à l’approche du festival Crear | Résister | Transform : un festival dédié aux mouvements féministes ! de l’AWID, nous sommes parti·e·s d’une question qui relève davantage d’une observation de l’état du monde – un désir de déplacer le terrain : pourquoi nos sexualités et nos plaisirs continuent-ils d’être apprivoisés et criminalisés, alors même qu’on nous répète sans cesse qu’ils n’apportent ni valeur ni progrès? Nous sommes arrivé·e·s à la conclusion que lorsqu’elles sont incarnées, quelque chose dans nos sexualités va à l’encontre d’un ordre mondial qui continue à se manifester par des contrôles aux frontières, des apartheids vaccinaux, un colonialisme d’occupation, un nettoyage ethnique et un capitalisme rampant. Pouvons-nous donc parler du potentiel perturbateur de nos sexualités? Pouvons-nous encore le faire lorsque, pour être financé·e·s, nos mouvements sont cooptés et institutionnalisés?

Lorsque notre travail incarné devient un profit entre les mains de systèmes que nous cherchons à démanteler, il n’est pas étonnant que nos sexualités et nos plaisirs soient une fois de plus relégués à la marge – surtout lorsqu’ils ne sont pas assez rentables. À plusieurs reprises au cours de la production de ce numéro, nous nous sommes demandé ce qui se passerait si nous refusions de nous plier aux services essentiels du capitalisme. Mais pouvons-nous oser poser cette question, lorsque nous sommes épuisé·e·s par le monde? Peut-être que nos sexualités sont si facilement rejetées parce qu’elles ne sont pas considérées comme des formes de soins. Peut-être que ce dont nous avons besoin, c’est de réimaginer le plaisir comme une forme de soin radical – un soin qui est également anticapitaliste et anti-institutionnel.

Alors que nous entrons dans notre deuxième année complète de pandémie mondiale, notre approche des incarnations transnationales a dû se concentrer sur un seul constat politique : prendre soin est une forme d’incarnation. Et parce qu’à l’heure actuelle, une grande partie de notre travail se fait sans tenir compte des frontières entre nous et en nous-mêmes, nous sommes toustes incarné·e·s de manière transnationale – et nous échouons toustes. Nous ne parvenons pas à prendre soin de nous-mêmes et, plus important encore, à prendre soin les un·e·s des autres.

Cet échec n’est pas de notre fait.

Beaucoup de nos parents considéraient le travail comme une transaction, quelque chose à donner en échange d’une compensation et d’une garantie de soins. Et bien que cet échange n’ait pas toujours été respecté, nos parents ne s’attendaient pas à ce que leur travail les comble. Iels avaient leurs loisirs, leurs passe-temps et leurs communautés pour cela. Aujourd’hui, nous, leurs enfants, qui avons été conditionné·e·s à penser que notre travail est intimement lié à notre passion, n’avons pas de telles attentes. Nous considérons le travail et les loisirs comme une seule et même chose. Pour un trop grand nombre d’entre nous, le travail en est venu à incarner tout notre être.

Cependant, le capitalisme hétéropatriarcal ne nous valorise pas, et encore moins notre travail ou nos sexualités. C’est un système qui ne fera qu’exiger toujours plus, jusqu’à votre mort. Et quand vous mourrez, il vous remplacera par quelqu’un·e d’autre. L’attente d’être en ligne 24 heures sur 24 signifie que nous ne pouvons tout simplement pas nous échapper du travail, même lorsque nous le souhaitons. Cette commercialisation du travail, qui le dissocie de la personne, a infiltré tous les aspects de nos vies et se perpétue même dans les milieux les plus féministes, les plus radicaux et les plus révolutionnaires.

Les attentes capitalistes ont toujours été particulièrement pernicieuses pour les corps qui ne correspondent pas à leur idéal. Et celleux qui cherchent à consolider leurs pouvoirs ont utilisé la pandémie comme une occasion de cibler les femmes, les minorités sexuelles et toustes celleux qu’iels considèrent comme des moins que rien.

Ce numéro spécial existe à cause, et certainement en dépit, de cela.

Presque tous les contributeur·ice·s et membres du personnel se sont surpassé·e·s. Chaque article est le fruit d’une passion, mais aussi d’un incroyable épuisement. De manière très concrète, ce numéro est une incarnation du travail transnational – et dans le monde numérique dans lequel nous vivons, tout travail est devenu un travail transnational. Alors que nous devons faire face à de nouvelles frontières qui ne brisent pas un ordre ancien mais le réifient, nous avons fait l’expérience directe, aux côtés de nos contributeurs, de la façon dont le capitalisme épuise nos limites – comment il devient difficile de construire des arguments cohérents, en particulier lorsque ceux-ci sont soumis à une date limite. Nous avons collectivement perdu les mots – parce que nous sommes perdu·e·s pour les mondes.

Se sentir perdu et seul dans le monde du capitalisme hétéropatriarcal est exactement la raison pour laquelle nous devons réévaluer et repenser nos systèmes de soins. À bien des égards, nous avons transformé ce numéro en une mission visant à trouver du plaisir dans les soins. Parce qu’il est devenu plus difficile de construire des arguments cohérents, les moyens visuels et créatifs sont passés au premier plan. Nombreux·ses sont celleux qui, ayant l’habitude d’écrire, se sont tourné·e·s vers ces médias pour produire des connaissances et couper court au brouillard mental qui nous a toustes enveloppé·e·s. Nous avons fait intervenir d’autres voix, en plus de celles que vous avez entendues au festival, afin d’ouvrir de nouvelles conversations et d’élargir nos horizons.

Alors que nous sommes privé·e·s de nos mots, il est de notre devoir politique de continuer à trouver des moyens de nous maintenir et de prendre soin de nous-mêmes et des autres. Une grande partie de nos réalités actuelles tente de nous effacer et de nous déplacer, tout en continuant à exploiter notre travail. Notre incarnation, par conséquent, devient une forme de résistance; c’est le début de nous-mêmes trouvant notre voie en dehors et en dedans de nous.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Las Mujeres Sostienen el Cuidado | El Cuidado Sostiene la Vida | La vida Sostiene la Economía | ¿Quién Cuida a las Mujeres? | Ni Una Menos1 | Juntas, Juntos, Juntes | Almuerzo de Domingo

1Nenhuna a menos se traduce literalmente como "ni una menos" en español, un eslogan feminista famoso en América Latina que surgió en Argentina como respuesta a la creciente violencia de género.

Día 3

Par Michel’le Donnelly

Le festival féministe Crear | Résister | Transform en septembre a été une véritable bouffée d'air frais en ces temps incertains, turbulents et douloureux.

L'espace créé par ce festival était absolument nécessaire. Nécessaire pour les âmes de ceux et celles qui cherchent du réconfort en ces temps les plus sombres. Nécessaire pour ceux et celles qui rêvent d’une communauté dans ce qui ressemble à un monde de plus en plus isolé et, par-dessus tout, nécessaire pour ceux et celles qui luttent contre les systèmes qui ont mis nombre d'entre nous à genoux, surtout au cours de ces deux dernières années.

«La crise n'est pas une nouveauté pour les mouvements féministes et sociaux, nous avons une longue histoire de survie face à l'oppression et cela fait longtemps que nous construisons nos communautés et nos propres réalités.»

Plaider pour des visions et des réalités alternatives à celle dans laquelle nous vivons actuellement constitue un élément fondamental du programme féministe. De nombreuses personnes extraordinaires œuvrent à explorer d'autres façons d'exister dans ce monde. Ces alternatives sont axées sur les personnes. Elles sont équitables et justes. Ces mondes sont remplis d'amour, de tendresse et d'attention. Les visions esquissées sont presque trop belles à imaginer, mais nous devons nous forcer à le faire car c'est la seule façon de continuer.

Au cours des dix derniers mois, j'ai eu la chance incroyable de travailler avec un collectif féministe qui ne se contente pas d'imaginer une réalité alternative, mais qui la vit activement. Nous nous inspirons du travail de nombreux autres mouvements féministes à travers le monde qui n'ont pas laissé le patriarcat capitaliste et suprémaciste blanc mettre un frein à leurs visions. Ce collectif m'a permis de tenir le coup alors que je ne demandais qu’à m'effondrer. À l'instar de l'histoire partagée par Maria Bonita le quatrième jour du festival, la libération à laquelle les mouvements féministes m’ont donné accès est bien trop importante pour que je sois la seule à en bénéficier. C'est quelque chose qui se partage, que nous devons crier sur les toits pour permettre aux autres de nous rejoindre.

Le quatrième jour du festival a été marqué par une conversation captivante entre Felogene Anumo, Dr. Dilar Dirik, Nana Akosua Hanson et Vandana Shiva, qui a encouragé les participant·e·s au festival à croire qu’un avenir alternatif était non seulement possible, mais qu'il était, de fait, urgent. Les féministes parlent de mondes alternatifs depuis tant d'années; entendre les panélistes en parler s’est avéré instructif, mais aussi réconfortant. Réconfortant dans le sens où je me suis sentie en sécurité à l’idée de savoir qu’il existe vraiment des réseaux féministes mondiaux solides travaillant au-delà des frontières internationales et nationales, cherchant à décoloniser les cadres établis de nos réalités actuelles.

Au cours de la session, Dr Dirik a souligné le fait que la croyance, le sacrifice et la patience sont d’une nécessité absolue si l’on veut abolir les systèmes oppressifs dans lesquels nous vivons actuellement. Collaboration, partenariat, créativité, solidarité et autonomie. Ce sont les piliers essentiels de la construction d'une société féministe mondiale et ils devraient être adoptés par tous les mouvements féministes du monde.

Des exemples pratiques de ces réalités peuvent être trouvés à travers le monde, notamment le Mouvement des femmes Soulaliyate pour les droits fonciers. Ce mouvement, qui fait référence aux femmes tribales du Maroc vivant sur des terres collectives, représente la première mobilisation communautaire à l’échelle nationale pour les droits fonciers au Maroc. Bien qu’initialement assez restreint, le mouvement s'est transformé en un programme national qui a remis en question la nature genrée des lois régissant les terres dans le pays. En 2019, le groupe a contribué à la refonte du cadre législatif national sur la gestion des biens communautaires par l'adoption de trois séries de lois garantissant l'égalité entre les femmes et les hommes.

La maison trans Zuleymi, au Pérou, est un autre exemple concret. Fonctionnant depuis 2016, cette maison est un refuge pour les femmes, les filles et les adolescent·e·s trans migrant·e·s que l'État a laissé·e·s pour compte. Elle a fourni un abri sûr à 76 femmes trans migrant·e·s du Venezuela, ainsi qu'à 232 autres provenant de la jungle, de communautés autochtones et de la côte nord du Pérou.

Il est incroyablement inspirant de découvrir ces mouvements féministes qui œuvrent à faire de ces futurs alternatifs une réalité et c’est exactement ce dont nous avons besoin, en particulier lorsque nous avons à affronter le flot incessant de mauvaises nouvelles qui semble couler sans interruption.

«Le patriarcat capitaliste est comme un cancer. Il ne sait pas quand s’arrêter de croître.»

- Dr Vandana Shiva

L'AWID a toujours été un mouvement inspiré par les réalités féministes dans lesquelles il nous est possible de vivre. Grâce à ses festivals, ainsi qu'au magazine et à la boîte à outils des Réalités féministes, l’AWID nous a montré une autre façon de faire les choses. Nous pouvons imaginer un monde où les soins sont prioritaires, où les économies féministes et la justice de genre sont la norme. C'est en créant des futurs alternatifs que nous ripostons, que nous résistons à la violence qui est perpétrée contre nos corps chaque jour.

Le festival Crear | Résister | Transform m’a permis de me sentir vraiment connectée aux membres d’une communauté mondiale, que je ne rencontrerai pour la plupart jamais. Le fait de savoir que nous travaillons tou·t·es à la création d'un autre monde a allumé un feu dans mon âme et j'ai hâte de voir ce que le prochain festival nous réservera.

Si vous l'avez manquée, assurez-vous de regarder la session «Elle est en route : alternatives, féminismes et un autre monde» de la quatrième journée du festival ci-dessous. Et souvenez-vous de ce que la Dr Shiva a dit avec tant d'éloquence : «L'énergie des femmes perpétuera la vie sur terre. Nous ne serons pas vaincues.»

|

Droits humains et ethno-territoriaux Assurer la défense des droits humains et des droits de la Nature par la construction d'alliances avec des acteur·rices et organisations locales, nationales, régionales et mondiales. |

|

Développement Durable Garantir que toutes les activités économiques, culturelles et environnementales contribuent au développement durable, à la sécurité alimentaire et à la génération de revenus, dans le respect de l'autodétermination et de l'autonomie gouvernementale des communautés afro-descendantes. |

|

Education and training Former les femmes et leur donner les moyens d'exercer la défense de leurs droits dans différents espaces politiques, sociaux et économiques. Pour plus d'informations, cliquez ici! |

¿Cuánto sabes sobre financiamiento feminista? 📊 Pon a prueba tu conocimiento sobre la movilización de recursos para el financiamiento de la organización feminista, respondiendo al cuestionario "¿Dónde está el dinero?":

Completa el quiz en línea Descarga la versión para imprimir

Queremos expresar nuestro más sincero agradecimiento a todos los diversos grupos, colectivos y organizaciones feministas de todo el mundo que respondieron a la encuesta WITM. Su participación y sus puntos de vista han sido inestimables y enriquecerán enormemente nuestra comprensión colectiva de los recursos feministas a nivel mundial.

I know you are so close. You can feel it can't you? How things need to shift and you need to centre yourself.

This is a letter to tell you to do it. Choose your healing. Choose to be OK. Better than OK. Choose to be whole, to be happy. To cry tears for yourself and no one else. Choose to shut out the world and tell them that 'you will be back in 5 mins'. Or five days. Or five years.

Or never.

Choose to not take it all on. Choose to take none of it on. Because none of it is yours. It was never yours. They told you since you were born that it was yours. Your family's problems. Your lovers' problems. Your neighbours' problems. The globe's problems. The constant whisper that these problems belong to you. They are yours. Yours to hold, yours to shoulder. Yours to fix.

That was a lie.

A bamboozle

A long con.

A scam.

The problems of the universe are not yours.

The only problems that are yours are your own. Everyone else can take a hike.

Allow yourself to drop everything and sprint off into the jungle. Befriend a daisy clad nymph, start a small library in the roots of a tree. Dance naked and howl at the moonlight. Converse with Oshun at the river bed.

Or simply drink a cup of tea when you need to take a moment to breathe.

Give yourself permission to disappear into the mist and reappear three countries over as a mysterious chocolatier with a sketchy past and penchant for dramatic cloaks and cigars.

Or stop answering work calls on weekends.

Let yourself swim to deserted island with a lover and dress only in the coconut shells from coconut rum that you make and sip at sunset.

Or say no when you don't have the capacity to create space for someone.

The options for holding yourself are endless.

Whatever you do, know the world will always keep spinning. That's the beauty and the pain of it. No matter who or what you choose over yourself and your soul the world will always keep spinning.

Therefore, choose you.

In the morning when that first light hits, choose you. When it’s lunchtime and it’s time to cry on company time, choose you. In the evening, when you are warming up leftovers because you didn’t have time to cook again, choose you. When anxiety wakes you up and existence is silent at 3:45 am.

Choose you.

Because the world will always keep twirling on a tilt and you deserve to have someone always trying to make it right side up for you.

Love,

Your dramatically cloaked jungle nymph.

|

|

|

|

|

Pour rendre visible la diversité des formes de financement de l’organisation des mouvements féministes.

«Mientras estaba en la primera línea de la protesta, fui sometida a violencia sexual, a lesiones físicas y a otras formas de violencia. Pero no me detendré hasta que logremos pleno gobierno civil en Sudán. Debemos impedir la militarización del Estado. Nuestros cuerpos no deben seguir siendo tratados como campos de batalla»

dijo Amal,1 una manifestante de 23 años.2

Durante los últimos cuatro años, las mujeres lideraron la revolución en Sudán. Su liderazgono fue solo callejero, sino que constituyó el poder que impulsó la resistencia constante en todos los niveles. Las mujeres y las jóvenes feministas se convirtieron en la conciencia alerta del movimiento de cambio y democratización sudanés. Desde la primera protesta del 13 de diciembre de 2018 contra el régimen anterior, en la ciudad de Aldmazein, en el área de conflicto del Nilo Azul, las jóvenes estudiantes fueron las voces que demandaron el fin de la dictadura de los militares y los Hermanos Musulmanes, que ya lleva treinta años en el poder.

El movimiento feminista, liderado por mujeres de entre 16 y 35 años, ha entablado una revolución dentro de la revolución en Sudán durante los últimos cuatro años de lucha ininterrumpida. Las potentes voces de las jóvenes que ocupan espacios en las calles, las redes sociales, la sociedad civil y las organizaciones políticas se elevaron lo suficiente como para reconfigurar la opinión pública y desafiar las normas sociales. Por primera vez en la historia de Sudán, las discusiones sobre violencia sexual y de género y sobre los tabúes de la violencia doméstica y los procesos de toma de decisiones dominados por los hombres se convirtieron en debates generalizados. Los equipos de fútbol de mujeres designaron voceras ante los comités de resistencia, y los sindicatos profesionales liderados por mujeres son parte de la expresión de la nueva ola del movimiento feminista de Sudán. El logro más importante es que las jóvenes se identifican como feministas en forma orgullosa y pública, en un país regido por el fundamentalismo islámico durante tres décadas. Los jóvenes varones que apoyan el activismo feminista -y se identifican como feministas- son otra señal de progreso notable.

Bajo el actual régimen del golpe militar, las jóvenes que lideran estas iniciativas y los grupos de mujeres que trabajan en el territorio no pueden mencionarse aquí debido a varios problemas de seguridad. Pero su resiliencia, su fuerza y su valentía serán incluidas en los libros de historia. Las audaces jóvenes que encabezan la resistencia en las calles y detrás de las pantallas, y que trabajan en diferentes profesiones y áreas de activismo están dando forma al futuro de Sudán. Las jóvenes feministas de Sudán están creando nuevos espacios para que las narrativas y los discursos feministas reestructuren la distribución del poder a nivel político, económico y social.

A pesar de la inmensa violencia, del resurgimiento del islamismo fundamentalista, de la militarización y de la reducción de los espacios cívicos, las activistas feministas de Sudán se mantienen arraigadas en su sororidad. Siguen siendo una gran inspiración para los movimientos feministas de todo el mundo.

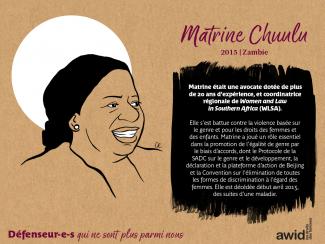

Nazik Awad

1 «Amal» es un seudónimo utilizado para proteger a la joven activista citada.

2 Desde 2018, Sudán vive en una revolución constante. Una nueva ola opositora arrancó a partir del golpe militar del 25 de octubre de 2021.

Siga el trabajo de estos colectivos en sus cuentas de redes sociales y sitios internet: