Berta Cáceres Flores

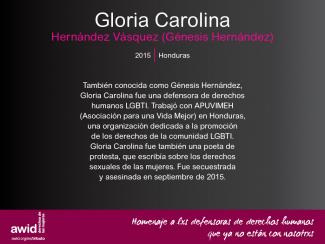

WHRDs are self-identified women and lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LBTQI) people and others who defend rights and are subject to gender-specific risks and threats due to their human rights work and/or as a direct consequence of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

WHRDs are subject to systematic violence and discrimination due to their identities and unyielding struggles for rights, equality and justice.

The WHRD Program collaborates with international and regional partners as well as the AWID membership to raise awareness about these risks and threats, advocate for feminist and holistic measures of protection and safety, and actively promote a culture of self-care and collective well being in our movements.

WHRDs are exposed to the same types of risks that all other defenders who defend human rights, communities, and the environment face. However, they are also exposed to gender-based violence and gender-specific risks because they challenge existing gender norms within their communities and societies.

We work collaboratively with international and regional networks and our membership

We aim to contribute to a safer world for WHRDs, their families and communities. We believe that action for rights and justice should not put WHRDs at risk; it should be appreciated and celebrated.

Promoting collaboration and coordination among human rights and women’s rights organizations at the international level to strengthen responses concerning safety and wellbeing of WHRDs.

Supporting regional networks of WHRDs and their organizations, such as the Mesoamerican Initiative for WHRDs and the WHRD Middle East and North Africa Coalition, in promoting and strengthening collective action for protection - emphasizing the establishment of solidarity and protection networks, the promotion of self-care, and advocacy and mobilization for the safety of WHRDs;

Increasing the visibility and recognition of WHRDs and their struggles, as well as the risks that they encounter by documenting the attacks that they face, and researching, producing, and disseminating information on their struggles, strategies, and challenges:

Mobilizing urgent responses of international solidarity for WHRDs at risk through our international and regional networks, and our active membership.

Este nuevo informe revela las realidades de los recursos de las organizaciones feministas y por los derechos de las mujeres en una época de turbulencias políticas y económicas sin precedentes. A partir de un análisis de más de una década desde el último informe de AWID ¿Dónde está el dinero? (Regando las hojas, dejando morir las raíces), se hace un balance de las conquistas, las brechas y las amenazas crecientes en el panorama del financiamiento.

En el informe se celebra el poder las iniciativas de los movimientos para configurar la dotación de recursos en sus propios términos y, a la vez, se da la voz de alarma sobre los recortes masivos de las ayudas, el declive de la filantropía y el aumento de las reacciones adversas.

Se hace un llamado a los donantes para que inviertan copiosamente en las organizaciones feministas, pues estas son la infraestructura esencial para la justicia y la liberación. También se invita a los movimientos a reinventar modelos audaces y autodefinidos para una dotación de recursos fundada en el cuidado, la solidaridad y el poder colectivo.

con Manal Tamimi, Bubulina Moreno, Karolina Więckiewicz y Anwulika Ngozi Okonjo

L’AWID a commencé à préparer ce rapport annuel au moment même où la pandémie mondiale commençait à bouleverser nos modes de rassemblement, d’organisation et de vie. Nous ne pouvons donc passer en revue notre travail sans prendre en compte l’influence de la COVID-19 dans notre évaluation.

Téléchargez le rapport annuel 2019 complet (PDF)

Elle est une affirmation urgente de l’existence d’autres façons, plus justes, d’organiser nos vies. En 2019, des centaines de groupes ont partagé avec nous leurs expériences et leurs propositions : des réseaux radicaux de soutien communautaire en Amérique latine, qui facilitent l’avortement autogéré, aux pratiques économiques centrées sur les communautés en Indonésie et aux systèmes alimentaires communautaires en Inde et aux États-Unis, en passant par une réinvention et une nouvelle pratique de rites de passage sans danger en Sierra Leone. Ce sont ces expériences qui traceront la voie d’une « nouvelle norme ».

Pour autant, les historiques d'oppression et de violence peuvent rendre l'imagination des possibles compliquée. Un élément clé de notre travail en 2019 a été d’initier ces pistes via la boîte à outils visant à soutenir les groupes qui cherchent à dénicher des histoires et des aspirations, piliers de propositions féministes.

Au sein de l'Observatoire de l'universalité des droits (OURs), de Feminists for a Bing Treaty (Féministes pour un traité contraignant), de Count Me In ! (Comptez sur moi!) et d’autres alliances, l’AWID n’a pas cessé de contrer le pouvoir débridé des entreprises et les agendas fascistes et fondamentalistes qui mettent à mal les droits des femmes et la justice de genre. Dans un contexte de perspectives sombres pour un changement transformateur par les processus multilatéraux et de capacités limitées à réagir pour la plupart des États, nous redoublons d'efforts pour nous assurer que les mouvements féministes, dans toute leur diversité, soient dotés de ressources adaptées aux rôles majeurs qu'ils jouent – en soutenant leurs communautés, en réclamant des droits et en répondant aux crises. En 2019, nous avons introduit des principes et des approches féministes aux fonds révolutionnaires tels que l'Initiative Spotlight et le Fonds Égalité. Nous avons de plus réussi à mobiliser des ressources via des aides à l’amorçage de réalités féministes, financées par des bailleurs féministes.

À l’heure où nous nous penchons vers l'avenir, le contexte appelle clairement à une transformation de nos stratégies d'organisation :

L’AWID se lance dans un nouveau modèle d'adhésion qui permet un meilleur accès et met l'accent sur les opportunités d'engagement et de connexion entre membres. Nous continuerons d'expérimenter différents outils et processus en ligne pour renforcer notre communauté. Et l'engagement inter-mouvements restera au cœur de notre travail. Nos actions solidaires envers les mouvements et les identités opprimées, même et surtout lorsqu’ils sont marginalisés, sont importantes pour conduire le changement et soutenir des mouvements, inclusifs pour tou·te·s.

Nous sommes résilient·e·s, nous nous adaptons et nous sommes présent·e·s les un·e·s pour les autres. Nous devrons continuer à faire encore mieux. Merci à toutes les personnes qui nous accompagnent dans cette aventure.

The Forum was a key space for the Indigenous Women’s Movement (IWM) in its relationship to feminism. At AWID Forums, they developed engagement strategies that would then apply at other spaces like the United Nations. In that process, both indigenous women and feminists movements were transformed: new voices and issues emerged and feminists started to change their discourses and practices around land rights and spirituality, they understood collective rights better, and included the IWM in their events and agendas. Mónica Alemán and María Manuela Sequeira, from the IWM, shared this story of change.

![]()

« Ma mission dans la vie n'est pas simplement de survivre, mais de prospérer; et de le faire avec un peu de passion, un peu de compassion, un peu d'humour et un peu de style. »

Le Forum international de l'AWID est à la fois un événement communautaire mondial et un espace de transformation personnelle radicale. Unique en son genre, le Forum rassemble les mouvements féministes, de défense des droits des femmes, de justice de genre, LBTQI+ et leurs allié.e.s dans toute leur diversité et leur humanité, afin qu'elles.ils se connectent, se soignent et s'épanouissent. Le Forum est un lieu où les féministes du Sud et les communautés historiquement marginalisées occupent le devant de la scène, élaborant des stratégies entre elles et avec les mouvements de justice sociale, afin de modifier le pouvoir, de créer des alliances stratégiques et d'ouvrir la voie à un monde différent et meilleur.

Lorsque les gens se rassemblent à l'échelle mondiale, en tant qu'individus et en tant que mouvements, nous générons une force considérable. Rejoignez-nous à Bangkok, en Thaïlande, en 2024. Venez danser, chanter, rêver et vous élever avec nous.

Quand : du 2 au 5 décembre 2024

Où : Bangkok, Thaïlande; et en ligne

Qui : Environ 2 500 féministes du monde entier participant en personne, et 3 000 participant virtuellement

La cumbre por el clima organizada por y para los movimientos.

📅 12 - 16 de noviembre de 2025

📍 Universidad Federal de Pará, Belém

avec Naike Ledan et Fédorah Pierre-Louis

La montée de la droite dans nombre de pays et le déluge de coupes dans les financements frappent durement la société civile de la Majorité mondiale ; le génocide en cours à Gaza, l’intensification des conflits violents au Soudan, la crise climatique à de nombreux endroits de notre planète : nous faisons face à des fascismes qui reviennent en force et un ordre mondial de l’impunité.

Téléchargez le rapport annuel 2024

Ensemble, nous pouvons construire un monde où la justice, la libération et la bienveillance ne sont pas des aspirations, mais des réalités.

Chaque année, à l’AWID, nous visons à renouveler et enrichir les points de vue et expériences que reflète notre Conseil d’administration (CA) en accueillant d’autres membres.

Nous sommes actuellement à la recherche de personnes pour servir des mandats de trois ans au CA de l’AWID, à partir du début de l’année 2024. Il s’agit d’une occasion de contribuer à la gouvernance de notre organisation, et d’intégrer un groupe extraordinaire de féministes du monde entier.

Merci de nous aider à identifier avant le 10 août 2023 des candidatures de féministes à la fois réfléchi·es et engagé·es .

Merci de transférer également cette invitation aux candidat·es dans vos réseaux

Nous recherchons avant tout des candidat·es engagé·es en faveur de la mission de l’AWID, qui peuvent faire le lien entre les luttes locales et mondiales. Ces personnes seront également en mesure de nous aider à tirer, de manière intentionnelle, le meilleur parti du positionnement et des atouts de l’AWID dans un contexte en constante évolution. Les candidat·es doivent être disposé·es à assumer les fonctions et endosser les responsabilités juridiques du CA de l’AWID, dans l’intérêt supérieur de l’organisation.

Il s’agit d’une fonction bénévole, qui nécessite une implication et un engagement tout au long de l’année. Il est attendu des membres du CA une participation à 10 à 15 journées de réunion par an minimum, en personne ou en ligne, et qu’elles et ils contribuent de leur temps et leur expertise, selon les besoins du CA.

Nous souhaitons que le CA reflète la diversité des mouvements féministes du monde entier, tant en matière d’identités que de géographies, de contextes et d’affiliations. Nous recherchons, en outre, des membres du CA ayant de l’expérience dans l’un des domaines de travail de l’AWID.

Nous invitons vivement tous les candidats à postuler. Nous étudierons toutes les candidatures reçues, mais compte tenu de la composition du CA actuel, nous accorderons la priorité à :

des candidatures démontrant une solide expérience dans les domaines suivants :

des candidatures des régions suivantes :

Le Conseil d’administration joue un rôle déterminant au niveau de la définition de l’orientation stratégique de l’AWID et du soutien à l’organisation dans l’accomplissement de sa mission, en cohérence avec le monde dans lequel nous vivons et les besoins de nos mouvements.

Les membres du CA contribuent au fonctionnement de l’organisation de diverses manières : en apportant une expérience d’autres espaces, des perspectives de divers mouvements féministes et un savoir-faire conséquent dans des domaines pertinents alignés sur la stratégie de l’AWID.

Les candidates élues et candidats élus rejoindront le CA de l’AWID en 2024 et nous accompagneront tout au long du tant attendu Forum international de l’AWID et de la mise en œuvre de notre plan stratégique.

(Vous pouvez déposer votre candidature ou celle d’une autre personne, avec son consentement.)

Merci de partager également cette invitation à candidatures au sein de vos réseaux !

D’avance, merci de votre aide à trouver les membres [MB2] extraordinaires de notre prochain Conseil d’administration, qui soutiendront l’AWID lors des étapes à venir !

Le thème du Forum − S'élever ensemble − est une invitation à nous engager avec tout notre être, à nous connecter les un.e.s aux autres de manière ciblée, bienveillante et courageuse, afin que nous puissions sentir le battement de cœur des mouvements mondiaux et nous élever ensemble pour relever les défis de notre époque.

Les mouvements féministes, de défense des droits des femmes, de justice basée sur le genre, LBTQI+ et autres mouvements apparentés du monde entier se trouvent à un tournant décisif, confrontés à un puissant revers/recul sur les droits et libertés précédemment acquis. Ces dernières années ont été marquées par la montée rapide des autoritarismes, la répression violente de la société civile et la criminalisation des femmes et des défenseuses.eurs des droits humains, l'escalade des guerres et des conflits dans de nombreuses régions du monde, la perpétuation des injustices économiques et les crises sanitaires, écologiques et climatiques qui s'entrecroisent.

Nos mouvements sont ébranlés et, en même temps, ils cherchent à construire et à maintenir la force et le courage nécessaires pour le travail à venir. Nous ne pouvons pas faire ce travail seul.e.s, dans nos bulles. La connexion et la guérison sont essentielles pour transformer les déséquilibres de pouvoir persistants et les lignes de faille au sein de nos propres mouvements. Nous devons travailler et élaborer des stratégies de manière interconnectée, afin de pouvoir prospérer ensemble. Le Forum de l'AWID favorise cet ingrédient vital qu'est l'interconnexion dans la pérennité, la croissance et l'influence transformatrice de l'organisation féministe à l'échelle mondiale.

Le 2 septembre 2021, les géniales féministes et activistes pour la justice sociale du festival de l’AWID Crear | Résister | Transform se sont retrouvées, non seulement pour mettre en commun leurs stratégies de résistance, cocréer et transformer le monde, mais également pour parler crûment sur Twitter.

Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah, cofondatrice du blog Adventures From The Bedrooms of African Women et autrice de The Sex Lives of African Women, menait l’exercice, épaulée par la plateforme numérique panafricaine womanist queer AfroFemHub, pour poser la question suivante : Comment pouvons-nous, de manière sûre et consensuelle, explorer notre plaisir, nos désirs et nos fantasmes par textos?

Je pense que c’est une question de très haute importance, parce qu’elle porte sur la question plus large de la navigation en ligne selon un point de vue féministe. Avec le capitalisme, le langage autour des corps et du sexe peut être déshumanisant et perturbant, et aborder le plaisir sexuel sur le numérique peut sembler devoir prendre une tournure performative. Donc, trouver des manières d’examiner comment nous faisons part de notre désir, qu’elles soient à la fois affirmatives et enthousiastes, peut repousser les modèles dominants de présentation et de consommation, et se réapproprier ces espaces comme autant de lieux d’un engagement authentique, prouvant que les sextos devraient tous être justement ça : féministes.

En outre, permettre aux conversations féministes d’incarner leur côté ludique dans les conversations en ligne contribue à recadrer le récit populaire selon lequel les interventions féministes sont tristes et austères. Mais nous le savons bien : s’amuser fait partie de notre politique, et est inhérent à ce qu’être féministe veut dire.

À l’aide du mot-dièse #SextLikeAFeminist des universitaires et des activistes du monde entier se sont donné rendez-vous pour partager leurs tweets féministes les plus affamés, et voici mes dix favoris.

Comme ces tweets le montrent, sextoter comme une féministe est à la fois sexy, drôle – et chaud. Mais sans jamais perdre de vue son engagement en faveur de l’équité et de la justice.

Inna es una activista y socióloga feminista queer. Posee muchos años de profundo compromiso con las luchas feministas y LGBTQI+, la educación en política y en procesos de organización de y para las mujeres migrantes, así como por la liberación de y la solidaridad con Palestina. Se incorporó a AWID en 2016 y cumplió diferentes funciones, la más reciente como Directora de Programas. Reside en Berlín (Alemania), creció en Haifa (Palestina/Israel), nació en San Petersburgo (Rusia), y ha puesto todo ese recorrido geográfico político y de resistencia a los colonialismos pasados y presentes al servicio del activismo feminista y la solidaridad transnacional.

Inna es autora de Women's Economic Empowerment: Feminism, Neoliberalism, and the State (Empoderamiento económico de las mujeres: Feminismo, neoliberalismo y Estado. Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), basado en la tesis que le valió un doctorado de la Universidad Humboldt de Berlín. Como académica, impartió cursos sobre globalización, producción de conocimientos, identidad y pertenencia. Inna posee una maestría en Estudios Culturales de la Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén. Integra la Junta de Jewish Voice for a Just Peace in the Middle East (Voces Judías por una Paz Justa en Medio Oriente, Alemania) y, con anterioridad, fue miembro de la Junta de +972 Advancement of Citizen Journalism (+972 Avance del Periodismo Ciudadano). Antes, Inna trabajó con la Coalición de Mujeres por la Paz y es una apasionada de la movilización de recursos para el activismo de base.

The “Where is the Money?” #WITM survey is now live! Dive in and share your experience with funding your organizing with feminists around the world.

Learn more and take the survey

Around the world, feminist, women’s rights, and allied movements are confronting power and reimagining a politics of liberation. The contributions that fuel this work come in many forms, from financial and political resources to daily acts of resistance and survival.

AWID’s Resourcing Feminist Movements (RFM) Initiative shines a light on the current funding ecosystem, which range from self-generated models of resourcing to more formal funding streams.

Through our research and analysis, we examine how funding practices can better serve our movements. We critically explore the contradictions in “funding” social transformation, especially in the face of increasing political repression, anti-rights agendas, and rising corporate power. Above all, we build collective strategies that support thriving, robust, and resilient movements.

Create and amplify alternatives: We amplify funding practices that center activists’ own priorities and engage a diverse range of funders and activists in crafting new, dynamic models for resourcing feminist movements, particularly in the context of closing civil society space.

Build knowledge: We explore, exchange, and strengthen knowledge about how movements are attracting, organizing, and using the resources they need to accomplish meaningful change.

Advocate: We work in partnerships, such as the Count Me In! Consortium, to influence funding agendas and open space for feminist movements to be in direct dialogue to shift power and money.

Dénoncer l’emprise des multinationales. Comprendre les fausses solutions. Construire des alternatives. Tout ce qu’il vous faut pour mener votre propre campagne « À qui appartient vraiment la COP ? ».

As these tweets show, it turns out that sexting like a feminist is sexy, funny – and horny. Yet, it never loses sight of its commitment to equity and justice.