Contenido relacionado

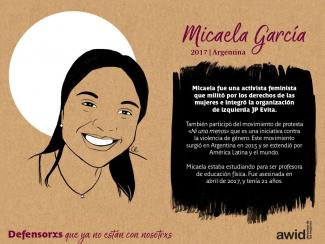

BBC Mundo: El terrible asesinato de la joven Micaela García que conmociona a Argentina

TeleSUR: América Latina, la región con más violencia hacia la mujer

WHRDs are self-identified women and lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LBTQI) people and others who defend rights and are subject to gender-specific risks and threats due to their human rights work and/or as a direct consequence of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

WHRDs are subject to systematic violence and discrimination due to their identities and unyielding struggles for rights, equality and justice.

The WHRD Program collaborates with international and regional partners as well as the AWID membership to raise awareness about these risks and threats, advocate for feminist and holistic measures of protection and safety, and actively promote a culture of self-care and collective well being in our movements.

WHRDs are exposed to the same types of risks that all other defenders who defend human rights, communities, and the environment face. However, they are also exposed to gender-based violence and gender-specific risks because they challenge existing gender norms within their communities and societies.

We work collaboratively with international and regional networks and our membership

We aim to contribute to a safer world for WHRDs, their families and communities. We believe that action for rights and justice should not put WHRDs at risk; it should be appreciated and celebrated.

Promoting collaboration and coordination among human rights and women’s rights organizations at the international level to strengthen responses concerning safety and wellbeing of WHRDs.

Supporting regional networks of WHRDs and their organizations, such as the Mesoamerican Initiative for WHRDs and the WHRD Middle East and North Africa Coalition, in promoting and strengthening collective action for protection - emphasizing the establishment of solidarity and protection networks, the promotion of self-care, and advocacy and mobilization for the safety of WHRDs;

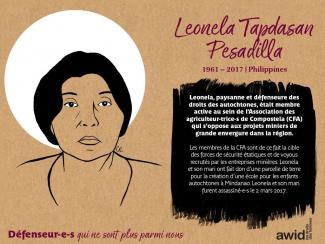

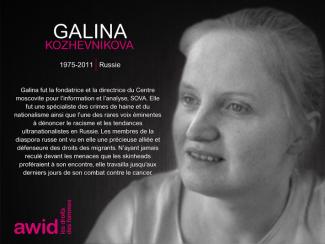

Increasing the visibility and recognition of WHRDs and their struggles, as well as the risks that they encounter by documenting the attacks that they face, and researching, producing, and disseminating information on their struggles, strategies, and challenges:

Mobilizing urgent responses of international solidarity for WHRDs at risk through our international and regional networks, and our active membership.

Effective as of 25 Apr 2023.

Please click here to view the previous version of our Privacy Policy.

This Privacy Policy describes how the Association for Women’s Rights in Development and our subsidiaries and affiliates (“AWID,” “we,” “us” or “our”) handles personal information that we collect through our website that links to this Privacy Policy (the “Site”), as well as through social media, our marketing activities, our live events and other activities described in this Privacy Policy (“Service”).

You can download a printable copy of this Privacy Policy here.

Index

Personal information we collect

How we use your personal information

How we share your personal information

Your choices

Other sites and services

Security

International data transfers

Children

Changes to this Privacy Policy

How to contact us

Notice to European users

Information you provide to us. Personal information you may provide to us through the Service or otherwise includes:

Automatic data collection. We, our service providers, and our business partners may automatically log information about you, your computer or mobile device, and your interaction over time with the Service, our communications and other online services, such as:

Cookies and similar technologies. Some of the automatic collection described above is facilitated by cookies, which are small text files that websites store on user devices and that allow web servers to record users’ web browsing activities and remember their submissions, preferences, and login status as they navigate a site. Cookies used on our sites include both “session cookies” that are deleted when a session ends, “persistent cookies” that remain longer, “first party” cookies that we place and “third party” cookies that our third-party business partners and service providers place.

We may use your personal information for the following purposes or as otherwise described at the time of collection:

Service delivery and business operations. We may use your personal information to:

Research and development. We may use your personal information for research and development purposes, including to analyze and improve the Service. As part of these activities, we may create aggregated, de-identified and/or anonymized data from personal information we collect. We make personal information into de-identified or anonymized data by removing information that makes the data personally identifiable to you. We may use this aggregated, de-identified or otherwise anonymized data and share it with third parties for our lawful business purposes, including to analyze and improve the Service and promote our business.

Marketing. We and our service providers may collect and use your personal information to send you direct marketing communications. You may opt-out of our marketing communications as described in the Opt-out of marketing section below.

Compliance and protection. We may use your personal information to:

With your consent. In some cases, we may specifically ask for your consent to collect, use or share your personal information, such as when required by law.

Cookies and similar technologies. In addition to the other uses included in this section, we may use the Cookies and similar technologies described above for the following purposes:

Retention. We generally retain personal information to fulfill the purposes for which we collected it, including for the purposes of satisfying any legal, accounting, or reporting requirements, to establish or defend legal claims, or for fraud prevention purposes. To determine the appropriate retention period for personal information, we may consider factors such as the amount, nature, and sensitivity of the personal information, the potential risk of harm from unauthorized use or disclosure of your personal information, the purposes for which we process your personal information and whether we can achieve those purposes through other means, and the applicable legal requirements.

When we no longer require the personal information we have collected about you, we may either delete it, anonymize it, or isolate it from further processing.

We may share your personal information with the following parties and as otherwise described in this Privacy Policy or at the time of collection.

Affiliates. Our corporate parent, subsidiaries, and affiliates, for purposes consistent with this Privacy Policy.

Service providers. Third parties that provide services on our behalf or help us operate the Service or our business (such as hosting, information technology, customer support, email delivery, marketing, consumer research and website analytics).

Payment processors. Any payment card information you use to make a purchase on the Service is collected and processed directly by our payment processors, such as Stripe. Stripe may use your payment data in accordance with its privacy policy, https://stripe.com/en-gb/privacy. You may also sign up to be billed by your mobile communications provider, who may use your payment data in accordance with their privacy policies.

Third parties designated by you. We may share your personal data with third parties where you have instructed us or provided your consent to do so. We will share personal information that is needed for these other companies to provide the services that you have requested. Moreover, you may choose to translate user-generated content using Google Translate. Google may use your user-generated content in accordance with its privacy policy, https://policies.google.com.Professional advisors. Professional advisors, such as lawyers, auditors, bankers and insurers, where necessary in the course of the professional services that they render to us.

Authorities and others. Law enforcement, government authorities, and private parties, as we believe in good faith to be necessary or appropriate for the compliance and protection purposes described above.

Other users. Your profile and other user-generated content data (except for messages) may be visible to other users of the Service. For example, other users of the Service may have access to your information if you chose to make your profile or other personal information available to them through the Service, such as when you provide comments, reviews, survey responses, or share other content. This information can be seen, collected and used by others, including being cached, copied, screen captured or stored elsewhere by others (e.g., search engines), and we are not responsible for any such use of this information.

In this section, we describe the rights and choices available to all users. Users who are located in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and the European Economic Area can find additional information about their rights below.

Opt-out of marketing communications. You may opt-out of marketing-related emails by following the opt-out or unsubscribe instructions at the bottom of the email, or by contacting us. Please note that if you choose to opt-out of marketing-related emails, you may continue to receive service-related and other non-marketing emails.

Declining to provide information. We need to collect personal information to provide certain services. If you do not provide the information we identify as required or mandatory, we may not be able to provide those services.

Delete your content or end your membership. You can choose to delete certain content you have provided to us. If you wish to request to end your membership, please contact us.

The Service may contain links to websites, mobile applications, and other online services operated by third parties. In addition, our content may be integrated into web pages or other online services that are not associated with us. These links and integrations are not an endorsement of, or representation that we are affiliated with, any third party. We do not control websites, mobile applications or online services operated by third parties, and we are not responsible for their actions. We encourage you to read the privacy policies of the other websites, mobile applications and online services you use.

We employ a number of technical, organizational and physical safeguards designed to protect the personal information we collect. However, security risk is inherent in all internet and information technologies and we cannot guarantee the security of your personal information.

We are headquartered in the United States and may use service providers that operate in other countries. Your personal information may be transferred to the United States or other locations where privacy laws may not be as protective as those in your state, province, or country.

Users in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and the European Economic Area should read the important information provided below about transfer of personal information outside of the European Union.

The Service is not intended for use by anyone under 18 years of age. If you are a parent or guardian of a child from whom you believe we have collected personal information in a manner prohibited by law, please contact us. If we learn that we have collected personal information through the Service from a child without the consent of the child’s parent or guardian as required by law, we will comply with applicable legal requirements to delete the information.

We reserve the right to modify this Privacy Policy at any time. If we make material changes to this Privacy Policy, we will notify you by updating the date of this Privacy Policy and posting it on the Service or other appropriate means. Any modifications to this Privacy Policy will be effective upon our posting the modified version (or as otherwise indicated at the time of posting). In all cases, your use of the Service after the effective date of any modified Privacy Policy indicates your acknowledgment that the modified Privacy Policy applies to your interactions with the Service and our business.

Where this Notice to European users applies. The information provided in this “Notice to European users” section applies only to individuals located in the EEA or the UK (EEA and UK jurisdictions are together referred to as “Europe”).

Personal information. References to “personal information” in this Privacy Policy should be understood to include a reference to “personal data” (as defined in the GDPR) – i.e., information about individuals from which they are either directly identified or can be identified. It does not include “anonymous data” (i.e., information where the identity of individual has been permanently removed). The personal information that we collect from you is identified and described in greater detail in the section “Personal information we collect”.

Our legal bases for processing. In respect of each of the purposes for which we use your personal information, the GDPR requires us to ensure that we have a “legal basis” for that use.

We have set out below, in a table format, the legal bases we rely on in respect of the relevant Purposes for which we use your personal information – for more information on these Purposes and the data types involved, see How we use your personal information above.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Retention. We retain personal information for as long as necessary to fulfill the purposes for which we collected it, including for the purposes of satisfying any legal, accounting, or reporting requirements, to establish or defend legal claims, or for compliance and protection purposes, unless specifically authorized to be retained longer.

To determine the appropriate retention period for personal information, we consider the amount, nature, and sensitivity of the personal information, the potential risk of harm from unauthorized use or disclosure of your personal information, the purposes for which we process your personal information and whether we can achieve those purposes through other means, and the applicable legal requirements.

When we no longer require the personal information, we have collected about you, we will either delete or anonymize it or, if this is not possible (for example, because your personal information has been stored in backup archives), then we will securely store your personal information and isolate it from any further processing until deletion is possible. If we anonymize your personal information (so that it can no longer be associated with you), we may use this information indefinitely without further notice to you.

Other information

No obligation to provide personal information. You do not have to provide personal information to us. However, where we need to process your personal information either to comply with applicable law or to deliver our Services to you, and you fail to provide that personal information when requested, we may not be able to provide some or all of our Services to you. We will notify you if this is the case at the time.

No Automated Decision-Making and Profiling. As part of the Services, we do not engage in automated decision-making and/or profiling, which produces legal or similarly significant effects. We will let you know if that changes by updating this Privacy Policy.

Security. We have put in place procedures designed to deal with breaches of personal information. In the event of such breaches, we have procedures in place to work with applicable regulators. In addition, in certain circumstances (including where we are legally required to do so), we may notify you of breaches affecting your personal information.

Your rights

General. European data protection laws give you certain rights regarding your personal information. If you are located in Europe, you may ask us to take any of the following actions in relation to your personal information that we hold:

Exercising These Rights. You may submit these requests by email. See the How to contact us section above for our contact details. We may request specific information from you to help us confirm your identity and process your request. Whether or not we are required to fulfill any request you make will depend on a number of factors (e.g., why and how we are processing your personal information), if we reject any request you may make (whether in whole or in part) we will let you know our grounds for doing so at the time, subject to any legal restrictions. Typically, you will not have to pay a fee to exercise your rights; however, we may charge a reasonable fee if your request is clearly unfounded, repetitive or excessive. We try to respond to all legitimate requests within a month. It may take us longer than a month if your request is particularly complex or if you have made a number of requests; in this case, we will notify you and keep you updated.

Your Right to Lodge a Complaint with your Supervisory Authority. In addition to your rights outlined above, if you are not satisfied with our response to a request you make, or how we process your personal information, you can make a complaint to the data protection regulator in your habitual place of residence.

The Information Commissioner’s Office

Water Lane, Wycliffe House

Wilmslow - Cheshire SK9 5AF

Tel. +44 303 123 1113

Website: https://ico.org.uk/make-a-complaint/

Data Processing outside Europe; we are a US-based company and many of our service providers, advisers, partners or other recipients of data are also based in the US. This means that, if you use the Services, your personal information will necessarily be accessed and processed in the US. It may also be provided to recipients in other countries outside Europe.

It is important to note that that the US is not the subject of an ‘adequacy decision’ under the GDPR – basically, this means that the US legal regime is not considered by relevant European bodies to provide an adequate level of protection for personal information, which is equivalent to that provided by relevant European laws.

Where we share your personal information with third parties who are based outside Europe, we try to ensure a similar degree of protection is afforded to it in accordance with applicable privacy laws by making sure one of the following mechanisms is implemented:

You may contact us if you want further information on the specific mechanism used by us when transferring your personal information out of Europe.

Contenido relacionado

BBC Mundo: El terrible asesinato de la joven Micaela García que conmociona a Argentina

TeleSUR: América Latina, la región con más violencia hacia la mujer

自2019年年末在印尼發生的一連串事件中,我們觀察到了當地軍事緊張與對同志權益的反彈跡象,AWID希望多元的與會者能在論壇齊聚一堂,但這讓我們自問是否能為與會者維持合理安全和讓人感到被歡迎的環境。

經過仔細商討後,AWID董事會在2019年11月決定將第十四屆AWID國際論壇的舉辦地點由峇里島改至台北。

台北擁有穩健的勤務服務能力,對旅客友善(針對國際論壇參與者提供便利的電子簽證流程)。

更多資訊請見以下 :

Panel: en las discusiones de panel, explora un tema o un desafío desde diferentes perspectivas, o comparte un aprendizaje o una experiencia, con preguntas del público a continuación, si el tiempo lo permite.

Programa de entrevistas: puedes tener una conversación más espontánea al estilo de un programa de entrevistas. Estos programas de entrevistas pueden ser una conversación entre varias personas, facilitadas por la persona que presenta el programa. Las preguntas del público pueden determinar la dirección de la conversación.

Conversación: estas pueden tomar la forma de «world café», de pecera y de otras metodologías que facilitan el involucramiento activo de lxs participantes en las conversaciones. Es un formato sumamente participativo.

Taller: actividades o clases interactivas que invitan a lxs participantes a adquirir nuevas habilidades en cualquiera y todas las áreas de la vida y el activismo.

Sesión estratégica: esta es una invitación a pensar en profundidad sobre un tema o una estrategia, junto con otras personas. Un espacio para aprender unxs de otrxs: qué funciona, qué no funciona, y cómo desarrollamos estrategias nuevas y colectivas para crear los mundos que soñamos.

Círculo para compartir [«birds of a feather»]: ideal para grupos pequeños, en un ambiente más íntimo, para oírse unxs a otrxs, iniciar una conversación y tratar con cuidado temas que pueden ser específicos, sensibles y complejos.

Artes – Taller participativo: actividades participativas de arte y expresión creativa. Ya sea a través de artes visuales, teatro, cine, pintura mural, danza, música, creación de artesanías y obras de arte colectivas, etc., apreciamos todas las ideas que celebren el arte y la creatividad feministas como formas de cambio social, sanación, expresión y transformación.

Artes – Performances, instalaciones y exhibiciones: son bienvenidas todas las propuestas que ofrezcan a lxs participantes del Foro nuevas experiencias y perspectivas, que expandan nuestros horizontes y que nos desafíen e inspiren para pensar, sentir y organizarnos de manera innovadora.

Sanación: actividades diversas diseñadas tanto para grupos como para personas individuales: desde aprender técnicas de relajación hasta hablar sobre la prevención del desgaste, desde prácticas informadas por el trauma para el cuidado de nuestro cuerpo, nuestra mente y nuestra alma hasta la reparación de fisuras dentro de nuestros movimientos.

Las rosas son rojas

Las violetas son azules

Viene la revolución

Y te vienes tú

El calendario nos invita a sumergirnos en el inspirador mundo del arte feminista. Conforme se despliega, cada mes brinda una vívida pieza de artistas feministas y queer de nuestras comunidades. Sus creaciones no son meras imágenes: son, en cambio, narraciones profundas que resuenan con las experiencias de lucha, de conquistas y de valentía imperecederas que definen nuestra búsqueda colectiva. Las historias visuales desbordantes de color y emoción sirven para acortar distancias y tejer juntxs nuestras experiencias diversas para acercarnos en nuestras misiones compartidas.

Con este calendario te hacemos un pedido: Úsalo, imprímelo, compártelo. Que sea una compañía diaria en tu viaje, un recordatorio constante de nuestra interconexión y nuestras visiones compartidas de un mundo mejor.

Deja que te inspire, como nos inspira a todxs nosotrxs, para continuar avanzando juntxs.

¡Consíguelo en tu idioma preferido! |

| English |

| Français |

| Español |

| Português |

| عربي |

| Русский |

| Thai |

Por primera vez, el Foro de AWID ofrece tres modos de participación:

Lxs participantes se reunirán en Bangkok, Tailandia. ¡No podemos esperar!

لمزيد من الأسئلة، يرجى استخدام نموذج الاتصال. سنستمر في تحديث هذه الوثيقة بناءً على الاستفسارات التي نتلقاها منك!

เรายินดีรับข้อเสนอกิจกรรมจากหลากหลายสาขาที่เชื่อมโยงกับแนวคิดสตรีนิยมและความยุติธรรมทางเพศ ในแบบฟอร์มใบสมัครนั้น ท่านจะสามารถทำเครื่องหมายเลือกประเด็นหลักที่เหมาะกับกิจกรรมของท่านได้ มากกว่าหนึ่งหัวข้อ

Zuhour Mahmoud is the Communication Strategist at Kohl. She is a writer and an editor, and an occasional DJ based in Berlin. Her work focuses on critical approaches to music, technology and politics and their life cycles within the digital sphere.