Mariel Araya

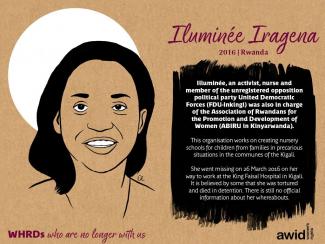

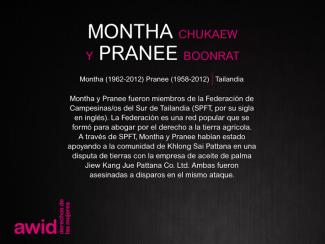

WHRDs are self-identified women and lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LBTQI) people and others who defend rights and are subject to gender-specific risks and threats due to their human rights work and/or as a direct consequence of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

WHRDs are subject to systematic violence and discrimination due to their identities and unyielding struggles for rights, equality and justice.

The WHRD Program collaborates with international and regional partners as well as the AWID membership to raise awareness about these risks and threats, advocate for feminist and holistic measures of protection and safety, and actively promote a culture of self-care and collective well being in our movements.

WHRDs are exposed to the same types of risks that all other defenders who defend human rights, communities, and the environment face. However, they are also exposed to gender-based violence and gender-specific risks because they challenge existing gender norms within their communities and societies.

We work collaboratively with international and regional networks and our membership

We aim to contribute to a safer world for WHRDs, their families and communities. We believe that action for rights and justice should not put WHRDs at risk; it should be appreciated and celebrated.

Promoting collaboration and coordination among human rights and women’s rights organizations at the international level to strengthen responses concerning safety and wellbeing of WHRDs.

Supporting regional networks of WHRDs and their organizations, such as the Mesoamerican Initiative for WHRDs and the WHRD Middle East and North Africa Coalition, in promoting and strengthening collective action for protection - emphasizing the establishment of solidarity and protection networks, the promotion of self-care, and advocacy and mobilization for the safety of WHRDs;

Increasing the visibility and recognition of WHRDs and their struggles, as well as the risks that they encounter by documenting the attacks that they face, and researching, producing, and disseminating information on their struggles, strategies, and challenges:

Mobilizing urgent responses of international solidarity for WHRDs at risk through our international and regional networks, and our active membership.

Cuando miles de feministas se unen, creamos una fuerza arrolladora de solidaridad que tiene el poder de cambiar el mundo. El Foro de AWID será un momento para que descansemos y nos recuperemos juntas, nos conectemos más allá de las fronteras y descubramos nuevas y osadas direcciones estratégicas.

La fecha y el lugar se anunciarán el próximo año, tan pronto como podamos. Estamos emocionades y sabemos que ustedes también lo están. ¡Manténganse al tanto!

¡Asegúrate de seguirnos en las redes sociales y suscríbete a nuestra lista de correo para mantenerte al día!

We have partnered with Global Voices for a special series of pieces for Pride Month 2023 (include music, video, and stories!) engaging with the intersectional issues that queer individuals and communities face around the world.

Avec Dre Vandana Shiva, Dre Dilar Dirik et Nana Akosua Hanson..

Cette histoire raconte comment un groupe toujours plus diversifié de féministes du Pacifique s’est organisé au fil des ans pour participer aux Forums de l’AWID et comment ce qu’elles ont découvert, appris et vécu au cours de ce processus les a transformées à la fois personnellement, en tant qu’organisations et en tant que mouvement. Elle illustre à quel point les Forums sont des espaces offrant aux régions qui ont tendance à être mondialement marginalisées ou ignorées la possibilité d’établir une forte présence au sein du mouvement féministe, laquelle peut ensuite être reproduite dans d’autres espaces internationaux de défense des droits des femmes.

Nouveau

En tant que participant.e en ligne, vous pouvez animer des sessions, vous connecter et converser avec d'autres, et faire l'expérience directe de la créativité, de l'art et de la célébration du Forum de l'AWID. Les participant.e.s connecté.e.s en ligne bénéficieront d'un programme riche et varié, allant des ateliers et des discussions aux séances de guérison et aux spectacles musicaux. Certaines activités seront axées sur la connexion entre les participant.e.s en ligne, tandis que d'autres seront véritablement hybrides, se concentrant sur la connexion et l'interaction entre les participant.e.s en ligne et celles.ceux qui se trouvent à Bangkok.

قضايا تتعلق بالجسد والجندر ومختلف أنواع الجنسانية، واستكشف الروابط المتشابكة بين القضايا هذه وكونها تجاربَ مجسّدة بعمق ومكانًا يُعترض فيه على الحقوق تكون فيه الأخيرة مهدّدة في المجتمع.

تكمن قوّة الحركات النسوية في طريقة تنظيمنا وتنسيق نشاطنا، ليس ضمن مجتمعاتنا وحركاتنا فحسب إنما بالتعاون مع قضايا ومجموعات حليفة في مجال العدالة الاجتماعية. وفّرت المساحة هذه فرصًا للحركات لمشاركة طرق التنظيم واستراتيجيات تكتيكية مع بعضنا البعض وتعزيزها.

لقد أوضحت جائحة كوفيد-١٩ العالمية فشل الرأسمالية النيوليبرالي فبدا أكبر من قبل وكشفت عن التفكك الموجود في أنظمتنا أكثر من أي وقت سابق، فشددت على ضرورة بناء أنواع واقع جديد وفرص بنائها. يتطلّب التعافي النسوي الاقتصادي والاجتماعي منّا جميعًا أن ننجح كلّنا معًا. نصدر النسخة هذه من المجلة بالشراكة مع «كحل: مجلة لأبحاث الجسد والجندر»، وسنستكشف عبرها الحلول والاقتراحات وأنواع الواقع النسوية لتغيير عالمنا الحالي وكذلك أجسادنا وجنسانياتنا.

يمكنك تصفح المقالات عبر الإنترنت أو

قم بتنزيل ملف PDF

The Forum was a key space for the Indigenous Women’s Movement (IWM) in its relationship to feminism. At AWID Forums, they developed engagement strategies that would then apply at other spaces like the United Nations. In that process, both indigenous women and feminists movements were transformed: new voices and issues emerged and feminists started to change their discourses and practices around land rights and spirituality, they understood collective rights better, and included the IWM in their events and agendas. Mónica Alemán and María Manuela Sequeira, from the IWM, shared this story of change.

Nous acceptons les candidatures dans toute la gamme des domaines thématiques et des intersections importantes pour les mouvements féministes et de justice de genre. Dans le formulaire de candidature, vous pourrez cocher plus d'un thème correspondant à votre activité/atelier.