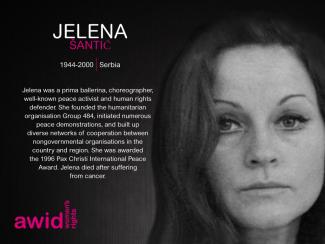

Jelena Santic

WHRDs are self-identified women and lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LBTQI) people and others who defend rights and are subject to gender-specific risks and threats due to their human rights work and/or as a direct consequence of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

WHRDs are subject to systematic violence and discrimination due to their identities and unyielding struggles for rights, equality and justice.

The WHRD Program collaborates with international and regional partners as well as the AWID membership to raise awareness about these risks and threats, advocate for feminist and holistic measures of protection and safety, and actively promote a culture of self-care and collective well being in our movements.

WHRDs are exposed to the same types of risks that all other defenders who defend human rights, communities, and the environment face. However, they are also exposed to gender-based violence and gender-specific risks because they challenge existing gender norms within their communities and societies.

We work collaboratively with international and regional networks and our membership

We aim to contribute to a safer world for WHRDs, their families and communities. We believe that action for rights and justice should not put WHRDs at risk; it should be appreciated and celebrated.

Promoting collaboration and coordination among human rights and women’s rights organizations at the international level to strengthen responses concerning safety and wellbeing of WHRDs.

Supporting regional networks of WHRDs and their organizations, such as the Mesoamerican Initiative for WHRDs and the WHRD Middle East and North Africa Coalition, in promoting and strengthening collective action for protection - emphasizing the establishment of solidarity and protection networks, the promotion of self-care, and advocacy and mobilization for the safety of WHRDs;

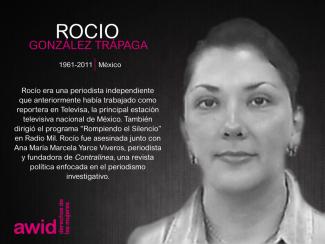

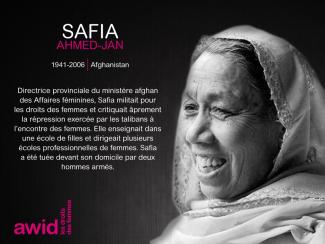

Increasing the visibility and recognition of WHRDs and their struggles, as well as the risks that they encounter by documenting the attacks that they face, and researching, producing, and disseminating information on their struggles, strategies, and challenges:

Mobilizing urgent responses of international solidarity for WHRDs at risk through our international and regional networks, and our active membership.

Los discursos anti-derechos continúan evolucionando. Además de utilizar argumentos relacionados con la religión, la cultura y la tradición, los actores antiderechos cooptan el lenguaje de la justicia social y los derechos humanos para ocultar sus verdaderas agendas y ganar legitimidad.

Hace tres décadas, un evangelista televisivo estadounidense candidato del Partido Republicano dijo una célebre frase: el feminismo es «un movimiento político antifamilia que alienta a las mujeres a dejar a sus maridos, matar a sus hijos, practicar brujería, destruir el capitalismo y convertirse en lesbianas». Hoy en día, esta idea conspirativa ha logrado un alcance y una legitimidad sin precedentes bajo la forma del discurso de la «ideología de género», un término genérico que, cual enemigo imaginario, ha sido creado por los actores antiderechos para oponerse a él.

Dentro de la serie de discursos empleados por los actores antiderechos (que incluyen nociones de «imperialismo cultural» y «colonización ecológica», apelaciones a la «objeción de conciencia» y la idea de un «genocidio prenatal»), un tema clave es la cooptación. Los actores antiderechos se apropian de problemáticas legítimas, o seleccionan partes de estas, y las distorsionan al servicio de sus agendas opresivas.

Sanyu es una feminista que reside en Nairobi (Kenia). Ha dedicado los últimos 10 años a apoyar a los movimientos obreros, feministas y por los derechos humanos, promoviendo la rendición de cuentas empresarial, la justicia económica y la justicia de género. Ha trabajado con el Centro de Información sobre Empresas y Derechos Humanos, en International Women’s Rights Action Watch Asia y el Pacífico (IWRAW, Observatorio Internacional de los Derechos de las Mujeres) y la Iniciativa de Derechos Humanos de la Commonwealth. Posee una maestría en Leyes y Derechos Humanos y una licenciatura en Derecho de la Universidad de Nottingham. Sus escritos se han publicado en el Business and Human Rights Journal, Human Rights Law Review, y plataformas como Open Global Rights, Democracia Abierta, entre otras. En sus ratos libres, le gusta caminar por el bosque y perseguir mariposas.

by Fatima B. Derby

In 2017, the AWID #PracticeSolidarity campaign highlighted how young feminists could build feminist futures by showing up for one another, being in cross-regional conversations with one another, marching in solidarity with other activists and collaborating between movements. (...)

< artwork: “Let it Grow” by Gucora Andu

✉️ Les inscriptions en personne sont closes. Inscrivez-vous au livestream ici

Événement en anglais

📅 Mercredi 12 mars 2025

🕒 12.00h-13.30h EST

🏢 PNUD, 304 E 45th St. Doha Room, 11th Floor (FF Building)

Organisé par : PNUD, Femena, SRI et AWID

Binta Sarr fue una activista por la justicia social, económica, cultural y política, y una ingeniera hidráulica en Senegal. Después de 13 años en la administración pública, Binta dejó ese camino para trabajar con mujeres rurales y marginadas.

Fue de este compromiso que surgió la Association for the Advancement of Senegalese Women [Asociación para el Avance de las Mujeres Senegalesas] (APROFES, por sus siglas en inglés), un movimiento y organización de base que Binta fundó en 1987. Uno de sus principales enfoques fue la formación de dirigentes, en relación no solo con las actividades económicas, sino también con los derechos de las mujeres y el acceso a los puestos de toma de decisiones.

"Las poblaciones de base deben organizarse, movilizarse, asumir el control ciudadano y exigir la gobernabilidad democrática en todos los sectores del espacio público. La prioridad de los movimientos sociales debe ir más allá de la lucha contra la pobreza y debe centrarse en programas de desarrollo articulados y coherentes en consonancia con los principios de los derechos humanos, teniendo en cuenta al mismo tiempo sus necesidades y preocupaciones tanto a nivel nacional como subregional y desde una perspectiva de integración africana y mundial". - Binta Sarr

Partiendo de la convicción de Binta de que el cambio fundamental de la condición de la mujer requiere una transformación de las actitudes masculinas, APROFES adoptó un enfoque interdisciplinario, al utilizar la radio, los seminarios y el teatro popular, además de proporcionar una educación pública innovadora y brindar apoyo cultural a las acciones de sensibilización. Su compañía de teatro popular representó piezas originales sobre el sistema de castas en el Senegal, el alcoholismo y la violencia conyugal. Binta y su equipo también analizaron la conexión crucial entre la comunidad y el mundo en general.

"Para APROFES, se trata de estudiar y tener en cuenta las interacciones entre lo micro y lo macro, lo local y lo global y también, las diferentes facetas del desarrollo. Desde la esclavitud hasta la colonización, el neocolonialismo y la mercantilización del desarrollo humano, la mayor parte de los recursos de África y del Tercer Mundo (petróleo, oro, minerales y otros recursos naturales) están todavía bajo el control de carteles financieros y las otras multinacionales que dominan este mundo globalizado". - Binta Sarr

Binta fue una de las integrantes fundadoras de la sección femenina de la Asociación Cultural y Deportiva Magg Daan. Recibió distinciones del Gobernador Regional y del Ministro de Hidrología por su "devoción por la población rural".

Nacida en 1954 en Guiguineo, un pequeño pueblo rural, Binta falleció en septiembre de 2019.

"La pérdida es inconmensurable, el dolor es pesado y profundo, pero resistiremos para no llorar a Binta; no lloraremos a Binta, mantendremos la imagen de su amplia sonrisa en todas las circunstancias, para resistir e inspirarnos en ella, para mantener, consolidar y desarrollar su obra..." - Página de Facebook de Aprofes, 24 de septiembre de 2019.

"¡Adiós Binta! Creemos que tu inmenso legado será preservado." - Elimane FALL , presidente de ACS Magg-Daan

|

Hind and Hind fue la primera pareja queer documentada en la historia árabe. En el mundo de hoy, es unx artista queer del Líbano. |

A los seis años, me enteré de que mi abuelo tenía una sala de cine. Mi madre me contó que la había abierto a principios de la década de 1960, cuando ella también tenía unos seis años. Recordaba que la primera noche proyectaron La novicia rebelde / Sonrisas y lágrimas.

Yo pasaba por el cine todos los fines de semana, y miraba a mi abuelo jugar al backgammon con sus amigos. No sabía que él estaba viviendo en la sala, en una habitación que estaba justo debajo de la cabina de proyección. Supe más tarde que se había mudado ahí después de que él y mi abuela se separaran, cuando el cine cerró, en los años 1990, poco después de que terminara la guerra civil en el Líbano.

Durante años, y hasta que él falleció, casi siempre veía a mi abuelo jugando al backgammon en el descuidado vestíbulo del cine. Esas escenas repetidas son todo lo que recuerdo de él. Nunca llegué a conocerlo bien, nunca hablamos de cine, aunque él pasaba todo su tiempo en una sala de cine destartalada. Nunca le pregunté cómo era vivir en un lugar como ese. Murió cuando yo tenía doce años, en Nochebuena, a causa de una caída por la escalera caracol que llevaba a la cabina de proyección. Resulta casi poético que haya fallecido en movimiento, en un edificio donde las imágenes animadas están permanentemente suspendidas en el tiempo.

En la primavera de 2020, mi primo me llamó para decirme que había limpiado el cine de mi abuelo, y me pidió que fuera allí para encontrarme con él. Lxs dos siempre habíamos soñado renovarlo. Llegué antes que él. En el vestíbulo seguían estando los marcos de los afiches de las películas, pero faltaban los afiches. Yo sabía que debían haber quedado talonarios de entradas en algún lado; los encontré apilados en una pequeña caja de latón oxidada, sobre un estante de la boletería, y me guardé algunos.

Empecé a dar vueltas por el cine. En el escenario principal, la pantalla de proyección estaba muy sucia y un poco rota en un costado. Deslicé mi dedo índice sobre la pantalla para quitar una mancha de polvo, y vi que, debajo, la pantalla todavía era blanca. La tela también parecía estar en buenas condiciones. Miré hacia arriba para ver si el telón de mi abuela todavía estaba colocado. Estaba hecho de satén blanco, con un pequeño emblema bordado que representaba al cine. Había una sala principal y una galería de palcos. Los asientos parecían muy desgastados.

Noté que el proyector asomaba por una ventanita al fondo del área de los palcos. Subí los escalones en espiral que llevaban a la cabina de proyección.

La habitación estaba a oscuras, pero un haz de luz, que entraba por las ventanas polvorientas, mostraba un montón de rollos de película arrojados en un rincón. Había cintas de celuloide inertes enredadas contra el pie del proyector. Los rollos polvorientos eran películas de género: westerns, cine de Bollywood y ciencia ficción con títulos malos como El meteorito que destruyó la Tierra o algo por el estilo. Me llamaron la atención las tiras de película polvorientas que, en su mayoría, eran fragmentos recortados de los rollos. Una por una, las tiras cortas mostraban diferentes escenas de besos, algo que parecía ser una danza sugerente, una escena indefinida de una reunión, un primer plano de una mujer acostada con la boca abierta, los créditos de apertura de una película de Bollywood, y una etiqueta de «Ahora en cartelera» que ocupaba varios fotogramas.

Los créditos de la película de Bollywood me recordaron a mi madre. Ella solía contarme que a la salida entregaban al público pañuelos de papel. Me guardé una escena de besos y las tiras de danza sugerente; supuse que habían sido cortadas por motivos de censura. El primer plano de la mujer me hizo pensar en los libros de Béla Balázs Visible Man, or The Culture of Film, The Spirit of Film y Theory of the Film. Él decía que en el cine los primeros planos proporcionan un

soliloquio silencioso, en el que un rostro puede hablar con los más sutiles matices de significado sin parecer antinatural y provocar la distancia de lxs espectadores. En este monólogo silencioso, la solitaria alma humana puede encontrar una lengua más sincera y desinhibida que en cualquier soliloquio hablado, porque habla instintivamente, en forma inconsciente.

Balázs estaba principalmente describiendo los primeros planos de Juana en la película muda La passion de Jeanne d’Arc. Señalaba cómo «... en la [película] muda, la expresión facial, aislada de su entorno, parecía penetrar en una nueva y extraña dimensión del alma».

Examiné más a fondo la tira de la película. La mujer parecía muerta, su cara era casi como una máscara. Me recordó al cuadro Ophelia del pintor John Everett Millais. En su libro Sobre la fotografía, Susan Sontag dice que una fotografía es «un rastro, algo directamente tomado de lo real, como una huella o una máscara mortuoria». Estas máscaras mortuorias son como una presencia que recuerda una ausencia.

Recordé haber encontrado un diálogo entre la muerte y la fotografía en la olvidada película de Roberto Rossellini La macchina ammazzacattivi [La máquina que mata a los malos]. En esta película, un camarógrafo va por ahí tomando fotos de personas, que a su vez se congelan, y luego quedan suspendidas en el tiempo. El crítico francés de cine André Bazin decía que la fotografía arrebata a los cuerpos del flujo de la muerte y los almacena embalsamándolos. Describía esta momificación fotográfica como «la preservación de la vida mediante la representación de la vida».

Esta cabina de proyección, toda su configuración, todas las cosas que parecían haber sido movidas, las tiras de celuloide en el piso, todo aquello en lo que mi abuelo había dejado una marca... sentí que debía protegerlo.

Debajo de las cintas había un rollo de película polvoriento y desarmado. Parecía que alguien había estado mirando el rollo manualmente. En ese momento, mi primo subió por la escalera caracol y me encontró estudiándolo. Se frotó el mentón con los dedos, y en tono muy objetivo dijo —Encontraste el porno.

Miré la tira de película que tenía en la mano, y me di cuenta de que no era una escena de muerte. La cinta había sido cortada del rollo porno. La mujer estaba gimiendo de éxtasis. Los primeros planos sirven para transmitir sentimientos de intensidad, de clímax, pero en realidad yo nunca había usado las teorías de Balázs para describir una escena porno. Él escribió que «el clímax dramático entre dos personas siempre será mostrado como un diálogo de expresiones faciales en primer plano». Me puse la tira de película en el bolsillo, y decidí llamar a la mujer Ishtar. Desde entonces, Ishtar ha vivido siempre en mi billetera. Parecía extraño comparar la minuciosa descripción de los miedos y el coraje de Juana de Arco con la expresión facial de Ishtar en éxtasis.

Según mi primo, el hermano de mi abuelo esperaba hasta que mi abuelo dejaba el cine y, en lugar de cerrar, invitaba a sus amigos para proyecciones privadas fuera de horario. No me pareció gran cosa. Era una práctica común, especialmente durante y después de la guerra civil del Líbano. Después de la guerra, había aparatos de televisión en casi todas las casas libanesas. Incluso recuerdo que había un televisor en mi dormitorio a finales de la década de 1990, cuando yo tenía unos seis años. Me han contado que comprar películas porno en VHS era algo generalizado en esa época. Mohammed Soueid, un escritor y cineasta libanés, me dijo una vez que, entre mediados de la década de 1980 y mediados de la de 1990, los cines solían proyectar tanto películas artísticas como pornográficas, para poder sobrevivir. También he oído que los proyeccionistas cortaban los rollos de porno para hacer diferentes montajes, y así poder proyectar algo distinto cada noche. Con el tiempo, la gente comenzó a quedarse dentro de la comodidad de sus propios hogares para mirar películas en VHS en sus televisores, y el negocio de los cines comenzó a declinar.

Mi primo volvió abajo para revisar un archivo de papeles que había en la oficina.

Yo me quedé en la cabina y empecé a pasar la tira de película entre mis dedos índice y medio, deslizándola hacia arriba con los pulgares y haciendo correr lentamente los fotogramas por mis manos. Alcé la tira contra la ventana polvorienta, y entrecerré los ojos para entender las viñetas monocromas. En esta serie de fotogramas había un primerísimo primer plano de una verga metida en una vagina. La imagen seguía durante varios fotogramas hasta que llegué a un nudo en la película, y me imaginé el resto.

Hank exhibe su erección frente a Veronika, quien está acostada en la cama al lado de un secrétaire imitación Luis XIV. Ella se levanta lentamente, y desliza el fino bretel de su negligé transparente para que le caiga del hombro izquierdo. Hank le desata la bata de velos, la gira, le da unas palmadas en el culo, y la empuja contra el secrétaire. Le mete la verga en el coño repetidamente, mientras la parte trasera del mueble golpea contra la pared empapelada.

Siempre presté atención a la decoración de interiores, desde la vez que mi profesora de Estudios sobre las Mujeres en la Pornografía dijo que los más grandes archivos de pornografía de América del Norte son utilizados, curiosamente, para examinar el amoblado de la clase media de la época. De modo que, mientras Veronika se agacha y es penetrada desde atrás por Hank, una asistente de investigación universitaria bien podría estar tratando de adivinar el diseño de la decoración dorada del secrétaire, o estudiando el relieve rococó de una silla de madera en algún rincón.

Por un momento, la cabina se convirtió en un espacio para la imaginación sexual femenina, desestabilizando un espacio que, de lo contrario, prometía la libertad de la sexualidad masculina. Estaba segura de que solo los hombres podían acceder a las salas de cine que proyectaban películas porno. El rollo de película estaba demasiado enredado como para arreglarlo en una cabina de proyección donde el polvo se había acumulado durante más de una década, así que lo metí en mi bolso de lona y me fui del cine.

No estoy segura de qué es lo que me ocurrió, pero me sentí obligada a conservarlo. Quería sentir la excitación de salvaguardar algo misterioso, algo no ortodoxo. Mientras iba por la calle, mentalmente estaba segura de que la gente sabía que yo estaba escondiendo algo. Me sobrevino un sentimiento de culpa mezclado con placer. Era algo perverso.

Entré en la casa, preocupada por la idea de tener un rollo pornográfico en mi bolsa de lona y por el fluir de los pensamientos que había tenido en el camino. Fui inmediatamente a mi dormitorio. En algún lugar lejano de mi mente, recordé que compartía una pared con la habitación de al lado, que era de Layla. Probablemente ella no estaba en casa, pero la posibilidad de que me oyeran me excitó. Cerré la puerta de mi dormitorio y saqué la tira de la película de Ishtar.

La imaginé con un vestido transparente color verde claro, bailando seductoramente frente a mí, sacudiendo sus caderas hacia los costados y sonriendo con los ojos. Me metí en la cama. Deslicé los dedos dentro de las bragas. Levanté mis caderas. Pasé la mano por mis muslos, hacia abajo, hasta separarlos, y me metí dos dedos. Me tensé, palpando mis diferentes pliegues. Empecé a gemir antes de poder detenerme. Jadeaba y me mecía. Los rayos de sol que entraban por mi ventana me daban besos renuentes sobre la piel. Aguanté la respiración, y mis brazos y mis piernas se estremecieron. Tragué el aliento y me quedé tumbada sobre el colchón.

Cuando era estudiante universitaria, tomé clases de introducción a la cinematografía. La profesora Erika Balsom había programado una proyección de Variety, de Bette Gordon. Estaba entusiasmada por ver la primera película de la productora Christine Vachon, quien después pasó a producir películas que ahora son parte del movimiento del Nuevo Cine Queer. Variety se describía como una película feminista sobre Christine, una mujer que comienza a trabajar en la boletería de un cine porno de Nueva York, llamado The Variety Theater. Christine oye las películas que se proyectan, pero nunca entra a la sala. Con el tiempo, se siente atraída por un cliente habitual, a quien observa atentamente. Lo sigue hasta una tienda de material pornográfico, en donde se aparta y hojea revistas para adultos por primera vez.

El voyeurismo de Christine se muestra de diferentes maneras a lo largo de la película. El guión también estaba plagado de excesos y de monólogos eróticos que podrían ser considerados obscenos o vulgares.

En una escena ambientada en una sala de juegos, ella le lee un texto erótico a su novio. La cámara va y viene entre un primer plano del culo de Mark mientras él juega al pinball, sacudiendo sus caderas hacia adelante y hacia atrás contra la máquina, y un primer plano del rostro de Christine mientras ella recita su monólogo.

«Sky estaba viajando a dedo y lo levantó una mujer en una pick-up. Era de noche tarde y él necesitaba un lugar donde quedarse, de modo que ella le ofreció su casa.

Ella le acompañó a su habitación y le ofreció un trago. Bebieron y hablaron, y decidieron ir a acostarse. Él no podía dormir, por lo que se puso los pantalones y fue por el pasillo hasta la sala de estar. Casi no podía ser visto, pero sí podía ver. La mujer estaba desnuda y extendida sobre la mesita baja, con las piernas colgando. Todo su cuerpo era de un blanco excitante, como si nunca hubiera estado expuesto al sol. Sus pezones eran color rosa brillante, como de fuego, casi de neón. Tenía los labios abiertos. Su largo cabello cobrizo lamía el suelo, los brazos estirados, los dedos cosquilleando el aire. Su cuerpo aceitado era redondo, sin puntas, sin bordes. Deslizándose entre sus senos había una gran serpiente que se curvaba hacia arriba alrededor de uno, y hacia abajo por el otro. La lengua de la serpiente lamía hacia el coño, tan abierto, tan rojo bajo la luz de la lámpara. Excitado y confundido, el hombre volvió a su habitación, y con gran dificultad logró dormirse. A la mañana siguiente, mientras comen frutillas, la mujer le pide que se quede otra noche. Otra vez, él no podía dormir […]»

Cuando tenía veintitrés años, Lynn, la chica del curso de cine con quien estaba saliendo, me sorprendió llevándome a mirar cortos eróticos el Día de San Valentín. El evento tenía lugar en el Mayfair Theater, un viejo cine independiente. La arquitectura del cine recordaba a los nickelodeons de América del Norte, pero con un toque exagerado. Los palcos estaban decorados con figuras de cartón de tamaño real de El monstruo del pantano y Aliens.

Ese año el jurado del festival era la estrella de cine para adultos Kacie May, y el programa consistía en una hora y media de cortometrajes. El contenido iba desde cortos machistas soft-core hasta películas de coprofilia. Miramos algunos minutos de lo que parecía ser porno suave heterosexual. La filmación mostraba a una pareja que empieza a hacer el amor en una sala de estar moderna, y luego pasa al dormitorio. Eran casi todas imágenes de ellxs besándose, tocándose, y haciendo el amor en la posición del misionero. Después, una mujer con cabello castaño corto se subió a la cama en cuatro patas, lamiendo el dorso de su propia mano a pequeños lengüetazos. Maullaba y se arrastraba sobre la despreocupada pareja. Continuaron haciendo el amor. Ella gateó hasta la cocina, levantó con los dientes su cuenco vacío, y lo colocó sobre una almohada. Siguió caminando encima de ellxs hasta el final del corto. Parecía bastante absurdo. Empecé a reírme, pero a Lynn se la veía un poco incómoda. Entonces, miré a nuestra izquierda, y vi a otras personas del público bebiendo cerveza a borbotones y atragantándose con palomitas de maíz mientras se reían como histéricxs. Sus risas ininterrumpidas y sus comentarios en voz bien alta eran lo que en verdad marcaban el tono del festival. Mirar al público resultó más interesante que mirar las películas eróticas. El Mayfair Theater a menudo proyectaba películas de culto, y mirar películas de culto es una experiencia comunitaria.

No es exactamente la forma en que yo me imaginaba al tío de mi madre mirando pornografía en el cine de mi abuelo. Los cines proyectaban abiertamente películas porno en esa época pero yo no podía imaginar eso sucediendo en el pueblo de mi madre. Lo imaginaba mirando la película desde el proyector de la cabina, para poder detener la proyección rápidamente en el caso de tener alguna visita inesperada. Sus amigos se sentaban en el palco del fondo. Nadie podía entrar por ahí a menos que tuviera una llave, así que era seguro. Tenían que pensar en todo. Era un barrio cristiano conservador, y no habrían querido causar problemas. Lo más probable era que estuvieran abrumados por la excitación y la culpa. Las voces de las bromas homoeróticas en voz alta se mezclaban con los audios de gruñidos y gemidos, pero cada pocos minutos se recordaban unos a otros que debían bajar la voz. Se turnaban para controlar las ventanas, asegurándose de que el sonido no fuera lo suficientemente alto como para alarmar a lxs vecinxs. A veces, apagaban el parlante y no había sonido.

En 2019, después de una protesta política, me encontré un puesto de libros en la calle Riad El Solh, cerca de la Plaza de los Mártires, en el centro de Beirut. Cerca del borde de la mesa, detrás de los libros de Víctor Hugo y Simone de Beauvoir, encontré una pila de novelas eróticas y revistas para adultos. Eran todas traducciones de publicaciones occidentales. En realidad no me importaba cuál elegir; solo sabía que quería tener un ejemplar, por la pura emoción. Busqué el arte de portada más interesante.

Mientras me daba el cambio, el vendedor me preguntó —¿No te conozco de algún lado? Me miró los pechos, deslizando los ojos hacia abajo. Probablemente supuso que yo trabajaba en la industria del porno o del sexo. Lo miré a los ojos y dije —No. Me di vuelta, lista para irme caminando con mi compra. Entonces, él me detuvo para decirme que tenía un gran archivo en su sótano, y que vendía regularmente colecciones y publicaciones porno en EBay a Europa y a los Estados Unidos. Si bien me interesaba revolver ese archivo, no me sentía lo suficientemente cómoda como para aceptar su oferta. No parecía seguro. Le pregunté dónde encontraba esas novelas. Para mi sorpresa, las editaban en el Líbano.

Caminando hacia la estatua de Riad El Solh, miré la publicación que había comprado y vi que el texto estaba algo torcido, con las letras un poco borroneadas, haciéndolas ilegibles. Las fotos internas eran collages pornográficos descoloridos. Parecía algo crudo; me gustaba. El título de la novela era Marcel’s Diaries [Los diarios de Marcel].

El arte de portada era claramente un recorte de una revista pegado sobre una hoja azul. En la ilustración, una mujer sin camisa está agarrando la cabeza de su amante, hundiendo los dedos en el cabello de él, mientras él le besa el cuello desde atrás. La falda de ella tiene el cierre abierto. Su amante tiene la mano apoyada en la zona inferior de su cadera derecha. La mano de ella está sobre la de él. Los labios de la mujer están fruncidos y abiertos, casi como si estuviera gimiendo de placer, y su cabello rubio y liso, al estilo de los años 1970, cae sobre su pecho y le cubre parcialmente los pezones.

Abrí el libro en la primera página. El prefacio decía:

que se puede traducir como

«Deseo

y desviación»

o como

«Deseo

y perversión»

Leí el primer capítulo, y descubrí que quien había traducido el texto había cambiado el nombre del protagonista a Fouad, que es un nombre árabe. Supuse que querían que su público masculino libanés se identificara. Continuando la lectura, vi que todas sus amantes tenían nombres extranjeros como Hanna, Marla, Marcel, Marta.

En la página 27, capítulo cuatro, me di cuenta de que Marcel era uno de los amantes de Fouad.

The scene took place in a movie theater. Movie theaters were often spaces for sexual freedom in North America, especially since the 1970s after the sexual revolution.

También supuse que habían mantenido todos los otros nombres extranjeros para que el texto sonara exótico y fuera por lo tanto menos tabú. La pornografía y las novelas eróticas eran atribuidas a West Hollywood, a pesar de que históricamente el mundo árabe haya producido textos eróticos. La literatura erótica se convirtió en tabú, y la única manera segura de editarla era comercializarla como extranjera, como exótica.

Es interesante cómo lo exótico encubre a lo erótico. La diferencia entre los dos adjetivos tiene su raíz en las etimologías griegas de las palabras: exótico viene de exo, «afuera», lo que significa extraño o extranjero. Erótico deriva de Eros, el dios del amor sexual. De modo que lo exótico es misterioso y extranjero, y lo erótico es sensual.

En el Líbano existe una línea delgada entre lo exótico y lo erótico en el cine, como la delgada línea entre las películas artísticas y las películas pornográficas. En 2015, durante una conversación con la cineasta Jocelyne Saab en un restaurante vietnamita de París, me enteré de que ella había tenido que filmar su película artística Dunia dos veces, para cambiar el dialecto del egipcio al libanés. Me contó que sus actorxs eran egipcixs, y que ella no era estricta respecto del guión. Pero no le permitieron usar el dialecto egipcio: tenía que ser en libanés, porque a los productores les preocupaban ciertas escenas de la película que bordeaban lo erótico. De modo que lo convirtieron en un film extranjero.

Originaire des Fidji, Veena Singh est féministe et femme de couleur. Élevée dans une petite commune rurale de ces îles, elle tire sa force de la richesse de son héritage mixte (sa mère est une femme autochtone fidjienne et son père est de descendance indo-fidjienne). L’identité et le vécu de Veena ont largement façonné son engagement envers la justice, l’équité et l’inclusion. Avec plus d’une vingtaine d’années d’expérience dans les droits humains, l’égalité des genres, l’épanouissement de la communauté et l’inclusion sociale, Veena croit passionnément qu’il faut faire bouger les lignes du pouvoir pour provoquer le changement transformateur qui permettra de construire l’économie de la bienveillance. Elle travaille dans des domaines très divers, notamment l’épanouissement de la communauté ; les femmes, la paix et la sécurité ; les politiques sociales ; les droits humains ; et le plaidoyer politique.

Elle est profondément engagée à faire avancer l’inclusion, la paix et la justice, la santé et les droits sexuels et reproductifs, la justice climatique, la justice transitionnelle et les droits humains. Elle possède une vaste expérience des réseaux de terrain, des organisations internationales et des institutions gouvernementales, et elle place toujours au centre les approches pilotées à l’échelle locale et par les communautés ainsi que les principes féministes.

En dehors de sa « vie de bureau », Veena est une défenseuse de l’environnement, de la santé mentale et c’est aussi une écrivaine. Mère de 11 chats, elle ne jure que par les saris et a un gros faible pour le courrier traditionnel et les cartes postales. Observatrice attentive des mouvements féministes aux Fidji et dans le Pacifique, Veena est en plein parcours personnel pour « décoloniser sa pensée et soi-même, en entreprenant une introspection radicale ». Par-dessus tout, elle est animée par le désir et le rêve de livrer des écrits auxquels pouvoir s’identifier, qui résonnent auprès des autres, en connectant avec la diaspora du Pacifique et en amplifiant les voix marginalisées.

Que représentent les Forums de l’AWID pour celles et ceux qui y ont assisté ? Quelle est cette magie qui opère lorsque des féministes du monde entier se rassemblent pour célébrer, élaborer des stratégies, apprendre et partager leurs joies ?

L’AWID s’est entretenue avec plus de quarante participant·es aux Forums pour connaître le récit de leur transformation personnelle en tant qu’activistes, celle de leur organisation et des mouvements auxquels elles et ils appartiennent. Elles et ils nous ont également dit ce que nous devrions conserver et renforcer pour les prochains Forums, ce qui distingue les Forums de l’AWID, et ce que nous pouvons améliorer.

Ce rapport contient des enseignements et d’inestimables conseils pour toute personne prévoyant d’organiser des rassemblements régionaux et thématiques en personne, et pour nous-mêmes alors que nous planifions le 15e Forum international de l’AWID.

por Gabriela Estefanía Riera Robles

Juliana. ¡Cómo quisiera llamarme Juliana! Es un nombre lleno de poder y presencia, lleno de fuerza y vehemencia. (...)

< arte: «Born Fighters», Borislava Madeit y Stalker Since 1993

✉️ By registration for larger groups. Drop-ins for smaller groups. Register here

📅 Wednesday, March 12, 2025

🕒 2.00-4.00pm EST

🏢 Chef's Kitchen Loft with Terrace, 216 East 45th St 13th Floor New York

Organizer: AWID

Laurie Carlos était une comédienne, réalisatrice, danseuse, dramaturge et poétesse aux États-Unis. Artiste hors pair et visionnaire, c’est avec de puissants modes de communication qu’elle a su transmettre son art.

« Laurie entrait dans la pièce (n’importe quelle pièce/toutes les pièces) avec une perspicacité déroutante, un génie artistique, une rigueur incarnée, une féroce réalité – et une détermination à être libre... et à libérer les autres. Une faiseuse de magie. Une devineresse. Une métamorphe. Laurie m’a dit un jour qu’elle entrait dans le corps des gens pour trouver ce dont ils et elles avaient besoin. » - Sharon Bridgforth

Elle a employé plusieurs styles de performance alliant les gestes rythmiques au texte. Laurie encadrait les nouveaux·elles comédien·ne·s, performeur·euse·s et dramaturges, et a contribué à développer leur travail dans le cadre de la bourse Naked Stages pour les artistes émergent·e·s. Associée artistique au Penumbra Theatre, elle a participé à la sélection de scripts à produire, dans l’objectif « d’intégrer des voix plus féminines dans le théâtre ». Laurie faisait également partie des Urban Bush Women, une compagnie de danse contemporaine reconnue qui contait les histoires de femmes de la diaspora africaine.

Elle fit ses débuts à Broadway dans le rôle de Lady in Blue, en 1976, dans la production originale et primée du drame poétique For colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf de Ntozake Shange. L’oeuvre de Laurie inclut White Chocolate, The Cooking Show et Organdy Falsetto.

« Je raconte les histoires à travers le mouvement – les danses intérieures qui se produisent spontanément, comme dans la vie – la musique et le texte. Si j’écris une ligne, ce n’est pas forcément une ligne qui sera dite ; ce peut être une ligne qui sera bougée. Une ligne à partir de laquelle de la musique est créée. Le geste devient phrase. Tant de ce que nous sommes en tant que femmes, en tant qu’êtres, tient aux gestes que nous exprimons les un·e·s par rapport aux autres, tout le temps, et particulièrement dans les moments d’émotion. Le geste devient une phrase, ou un état de fait. Si j’écris “quatre gestes” dans un script, cela ne signifie pas que je ne dis rien;cela veut dire que j’ai ouvert la voie à ce que quelque chose soit dit physiquement. » Laurie Carlos

Laurie est née et a grandi à New York, a travaillé et vécu à Minneapolis-Saint-Paul. Elle est décédée le 29 décembre 2016, à l’âge de 67 ans, après un combat contre le cancer du côlon.

« Je pense que c’était exactement l’intention de Laurie. De nous sauver. De la médiocrité. De l’ego. De la paresse. De la création artistique inaboutie. De la paralysie par la peur.

Laurie voulait nous aider à briller pleinement.

Dans notre expression artistique.

Dans nos vies. » - Sharon Bridgforth pour le Pillsbury House Theatre

« Quiconque connaissait Laurie aurait dit que c’était une personne singulière. Elle était sa propre personne. Elle était sa propre personne, sa propre artiste ; elle mettait en scène le monde tel qu’elle le connaissait avec un vrai style et une compréhension fine, et elle habitait son art. » – Lou Bellamy, Fondatrice de la Penumbra Theatre Company, pour le Star Tribune

Lire un hommage complet par Sharon Bridgforth (seulement en anglais)

|

Tshegofatso Senne est un·e féministe noir·e atteint·e d’une maladie chronique et genderqueer qui fait le maximum. Une grande partie de son travail est axée sur le plaisir, la communauté et le rêve et s’alimente de l’abolitionnisme somatique et du handicap, de la guérison et des justices transformatives. Tshegofatso écrit, fait des recherches et s’exprime sur des questions concernant le féminisme, la communauté, la justice sexuelle et reproductive, le consentement, la culture du viol et la justice, et élabore depuis 8 ans des théories sur la façon dont le plaisir recoupe ces différents thèmes. Tandis qu’iel dirige sa propre entreprise, Thembekile Stationery, sa plateforme communautaire Hedone rassemble les gens pour explorer et comprendre le pouvoir du plaisir et de la prise de conscience de traumatismes dans leur vie quotidienne. |

C’est dans notre corps, et non dans notre cerveau pensant, que nous expérimentons la plupart de nos douleurs, nos plaisirs, nos joies, et là où nous traitons la majeure partie de ce qui nous arrive. C’est également là que nous faisons la plupart de notre travail de guérison, et notamment notre guérison émotionnelle et psychologique. Et c’est là où nous faisons l’expérience de la résilience et d’une sorte de flux.

Ces mots, ceux de Resmaa Menakem dans son roman My Grandmother’s Hands résonnent toujours en moi

Le corps contient nos expériences. Nos mémoires. Notre résilience. Et comme l’a écrit Menakem, le corps contient également nos traumatismes. Il emploie des mécanismes spontanés de protection pour arrêter ou prévenir les dommages supplémentaires. Le pouvoir du corps. Le traumatisme, ce n’est pas l’événement, c’est la manière dont nos corps répondent aux événements qui nous semblent dangereux. Et le trauma reste souvent coincé dans notre corps, jusqu’à ce que nous l’abordions. Il n’est pas possible de faire autrement – c’est ainsi que notre corps l’entend.

En utilisant l’appli Digital Superpower de Ling Tan, j’ai observé les réactions de mon corps alors que je me promenais dans différents quartiers de ma ville, Johannesburg, en Afrique du Sud. L’appli est une plateforme en ligne pilotée par le mouvement qui permet de suivre nos perceptions pendant que l’on se déplace dans un lieu, en saisissant et en enregistrant les données. Je m’en suis servie pour faire le suivi de mes symptômes psychosomatiques – les réactions physiques connectées à une cause psychologique. Il pouvait s’agir de flash-backs. D’attaques de panique. De serrement de poitrine. L’accélération du rythme cardiaque. De maux de tête dus à la tension. De douleurs musculaires. D’insomnie. De difficulté à respirer. J’ai suivi ces symptômes tout en marchant et en me déplaçant dans différents coins de Johannesburg. Et je me suis demandé.e :

Où pouvons-nous être en sécurité? Peut-on être en sécurité?

Les réponses psychosomatiques peuvent avoir plusieurs causes, certaines moins sévères que d’autres. Lorsque l’on a vécu un traumatisme, on peut être dans une détresse très intense lors d’événements ou de situations similaires. J’ai fait le relevé de mes sensations, sur une échelle de 1 à 5, où 1 correspond aux cas où je n’ai ressenti presque aucun de ces symptômes – plutôt à l’aise que sur mes gardes et à fleur de peau, ma respiration et mon rythme cardiaque étaient stables, je ne regardais pas par-dessus mon épaule – et 5 à l’opposé : des symptômes qui me rapprochaient de l’attaque de panique.

En tant que personne noire. En tant que personne queer. En tant que personne de genre queer qui pouvait être perçue comme une femme, selon mon expression de genre ce jour-là.

Je me suis demandé.e :

Où pouvons-nous être en sécurité?

Même dans les quartiers que l’on pourrait considérer comme « sûrs », je me sentais constamment en panique. Je regardais autour de moi pour vérifier que je n’étais pas suivie, ajustant la manière dont mon T-shirt tombait pour que mes seins ne soient pas trop moulés, regardant autour de moi pour m’assurer que je connaissais plusieurs sorties, si je sentais tout à coup un danger là où j’étais. Une route sans personne fait monter l’anxiété. Une route bondée aussi. Prendre un Uber aussi. Marcher dans une rue publique également. Et être dans mon appartement aussi. Tout comme de récupérer une livraison au pied de mon immeuble.

Peut-on être en sécurité?

Pumla Dineo Gqola parle de l’usine de peurs féminines. Vous en avez peut-être une vague idée, mais si vous êtes une personne socialisée en tant que femme, vous connaîtrez très bien ce sentiment. Ce sentiment d’avoir à planifier chaque pas que vous faites, que vous vous rendiez au travail, à l’école, ou fassiez simplement une course. Ce sentiment d’avoir à surveiller la manière dont on s’habille, on parle, on s’exprime en public et dans les espaces privés. Ce sentiment au creux de l’estomac si on doit se déplacer la nuit, aller chercher une livraison, ou avoir affaire à toute personne qui continue à se socialiser en tant qu’homme cis. Harcelées dans la rue, toujours sous la menace de la violence. Exister pour nous, quel que soit l’espace, s’accompagne d’une peur innée.

La peur est un phénomène à la fois individuel et sociopolitique. Au niveau individuel, la peur peut faire partie d’un système d’avertissement sain qui se développe bien […] Lorsque l’on pense à la peur, il est important de prendre en compte à la fois les notions d’expérience émotive individuelle et les modalités politiques par lesquelles la peur a été utilisée à des fins de contrôle à diverses époques.

- Pumla Dineo Gqola, dans son ouvrage Rape: A South African Nightmare

En Afrique du Sud, les femmes cis, les femmes et les queers savent que chaque pas que nous faisons à l’extérieur – des pas pour faire des choses ordinaires comme se rendre dans un magasin, prendre un taxi jusqu’au travail, un Uber pour rentrer d’une fête – toutes ces actions sont une négociation avec la violence. Cette peur, elle fait partie du traumatisme. Pour s’adapter au traumatisme que l’on porte dans nos corps, nous élaborons des réponses à la détection du danger – on examine les réactions émotives des personnes autour de nous, à la recherche d’« amabilité ». Nous sommes constamment sur nos gardes.

Jour après jour. Année après année. Vie après vie. Génération après génération.

L’auteur de The Body Keeps the Score, Bessel van der Kolk, explique à propos de la difficulté supplémentaire que pose ce système de défense acquis, que

Elle perturbe la capacité à correctement lire les autres, ce qui rend les survivant·e·s de traumatisme moins à même de détecter le danger, ou plus à même de croire avoir perçu un danger là où il n’y en a pas. Il faut une énergie considérable pour continuer à fonctionner tout en portant la mémoire de la terreur, et la honte d’une faiblesse et d’une vulnérabilité infinie.

Comme le dit Resmaa Menakem, le traumatisme est partout; il s’infiltre dans l’air que nous respirons, l’eau que nous buvons, la nourriture que nous ingérons. Il est présent dans les systèmes qui nous gouvernent, l’institution qui nous enseigne et qui nous traumatise aussi, et au sein des contrats sociaux que nous concluons les un·e·s avec les autres. Plus important encore, nous prenons le traumatisme avec nous partout où nous allons, dans nos corps, nous épuisant et sapant notre santé et notre bonheur. Nous portons cette vérité dans nos corps. Des générations d’entre nous l’ont fait.

Alors, pendant que je marche dans ma ville, que ce soit dans un quartier considéré « sûr » ou non, je porte les traumatismes de générations dont les réactions sont intégrées dans mon corps. Mon cœur palpite, je commence à avoir du mal à respirer, ma poitrine se resserre – parce que mon corps a l’impression que le traumatisme a lieu exactement à ce moment-là. Je vis avec une hypervigilance. Au point où l’on est soit trop sur ses gardes pour profiter de la vie sans souci, soit trop engourdi·e pour absorber de nouvelles expériences.

Pour que nous commencions à guérir, nous devons reconnaître cette vérité.

Ces vérités qui vivent dans nos corps.

Ce traumatisme est ce qui empêche nombre d’entre nous de vivre les vies que nous voulons. Demandez à n’importe quelle femme ou personne queer à quoi ressemble la sécurité pour elle, et elle vous donnera principalement des exemples de tâches très simples – pouvoir simplement vivre une vie joyeuse, sans la menace constante de la violence.

Les sentiments de sécurité, de confort et d’aise sont spatiaux. Incarner nos traumatismes influence la manière dont nous percevons notre propre sécurité, affecte les manières dont nous interagissons avec le monde et modifie les possibilités pour nous de vivre et d’incarner toute chose plaisante ou joyeuse.

Nous devons refuser cette encombrante responsabilité et nous battre pour un monde sûr pour nous toutes et tous. Nous, qui nous déplaçons avec nos blessures, sommes des battantes. Le patriarcat peut nous terroriser et nous brutaliser, nous ne cesserons pas le combat. Alors que nous continuons à descendre dans la rue, en défiant la peur de manière spectaculaire et apparemment insignifiante, nous nous défendons et parlons en notre propre nom.

- Pumla Dineo Gqola, dans son ouvrage Rape: A South African Nightmare

Où pouvons-nous être en sécurité? Comment commencer à se défendre, pas simplement physiquement mais également émotionnellement, psychologiquement et spirituellement?

« Le traumatisme nous transforme en armes » déclarait Adrienne Maree Brown dans un entretien mené par Justin Scott Campbell. Et son ouvrage, Pleasure Activism, propose plusieurs méthodes pour guérir ce traumatisme et nous ancrer dans la compréhension que la guérison, la justice et la libération peuvent également être des expériences plaisantes. Et particulièrement pour celles d’entre nous qui sont les plus marginalisées, qui ont peut-être été éduquées à faire rimer souffrance avec « ce travail ». Ce travail que tant d’entre nous ont entamé en tant qu’activistes, bâtisseuses communautaires et travailleuses, celles qui sont au service des plus marginalisées, ce travail que nous souffrons à réaliser, nous épuisant et ne prenant que rarement soin de nos esprits et de nos corps. L’alternative est d’être mieux informées à propos de nos traumatismes, capables d’identifier nos propres besoins et de devenir profondément incarnées. Cette incarnation signifie que nous sommes tout simplement plus à même de faire l’expérience du monde à travers les sens et les sensations de notre corps, en reconnaissant ce qu’ils nous disent plutôt qu’en supprimant et en ignorant l’information qu’ils nous communiquent.

Être en conversation continue avec notre corps vivant et pratiquer ces conversations avec intention nous connecte plus profondément à l’incarnation. Cela nous permet de rendre tangibles les émotions que nous ressentons lorsque nous interagissons avec le monde, que nous apprenons à apprivoiser notre corps et que nous comprenons tout ce qu’il essaie de nous enseigner. En comprenant le traumatisme et l’incarnation de pair, nous pouvons commencer à débuter la guérison et à accéder au plaisir de manière plus holistique, sainement et dans notre vie de tous les jours sans honte ou culpabilité. Nous pouvons commencer à accéder au plaisir en tant qu’outil de changement individuel et social, en puisant dans le pouvoir de l’érotique, comme le décrivait Audre Lorde. Un pouvoir qui nous permet de partager la joie à laquelle nous accédons et dont nous faisons l’expérience, élargissant notre capacité à être heureuses et à comprendre que nous le méritons, même avec notre traumatisme.

Puiser dans le plaisir et incarner l’érotique nous gratifie de la possibilité d’être délibérément vivantes, de nous sentir ancrées et stables et de comprendre notre système nerveux. Cela nous permet de comprendre et de nous défaire des bagages générationnels que nous portions sans le réaliser; nous pouvons acquérir du pouvoir grâce à la connaissance que même aussi traumatisées que nous le sommes, aussi traumatisées que nous pourrions potentiellement l’être à l’avenir, nous méritons tout de même des vies plaisantes et joyeuses, et que nous pouvons partager ce pouvoir avec nos gens. C’est l’aspect communautaire qui manque aux manières dont nous prenons soin de nous-mêmes; l’autosoin ne peut exister sans soin communautaire. Nous sommes en mesure de sentir une confiance interne plus profonde, une sécurité et un pouvoir en nous-mêmes, particulièrement face à des traumatismes ultérieurs qui déclencheraient des réactions en nous, car nous savons comment nous apaiser et nous stabiliser. Toute cette compréhension nous mène à un pouvoir interne profond et nourri, qui nous permet de relever tous les défis qui se présentent à nous.

Comme celles qui vivent avec des traumatismes générationnels profonds, nous en sommes venues à perdre confiance, voire à penser que nous sommes incapables de contenir et d’accéder au pouvoir que nous avons. Dans « Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power », Lorde nous enseigne que l’érotique offre une source de régénération, une manière d’exiger mieux pour nous-mêmes et pour nos vies.

Car l’érotique n’est pas simplement une question de ce que nous faisons; c’est de savoir dans quelle mesure nous pouvons précisément et entièrement ressentir le faire. Dès lors que nous connaissons la mesure dans laquelle nous sommes capables de ressentir ce sens de satisfaction et de complétude, nous pouvons alors observer quelle activité dans notre vie nous rapproche le plus de cette complétude.

Je ne dis rien de tout ça à la légère – je sais que c’est plus facile à dire qu’à faire. Je sais que nombre d’entre nous sont empêchées de comprendre ces réalités, de les internaliser, voire de les guérir. La résistance s’accompagne d’actes où l’on se sent en insécurité, mais elle n’est pas impossible. Résister à des structures de pouvoir qui maintiennent les plus puissants en sécurité mettra toujours en danger celles d’entre nous qui sont poussées dans la marge. Reconnaître les traumatismes que vous avez affrontés, c’est réclamer vos expériences vécues, celles qui sont passées et celles qui suivront; c’est la résistance qui incarne cette connaissance que nous méritons, plutôt que les miettes que ces systèmes nous ont obligées à avaler. C’est une résistance qui comprend que le plaisir est compliqué par le traumatisme, mais que l’on peut y accéder de manière arbitraire et puissante. C’est une résistance qui reconnaît que notre traumatisme est une ressource qui nous connecte les unes aux autres et qui peut nous permettre de nous sentir mutuellement en sécurité. C’est une résistance qui comprend que même avec le plaisir et la joie, ce n’est pas une utopie; nous blesserons encore et serons de nouveau blessées, mais nous serons mieux outillées pour survivre et nous épanouir dans une communauté de soins et de gentillesse diversifiés. Une résistance qui fait de la place à la guérison et à la connexion à notre être humain en entier. La guérison ne sera jamais une balade agréable, mais elle commence avec la reconnaissance de la possibilité. Lorsque l’oppression nous fait croire que le plaisir est quelque chose auquel tout le monde a un accès égal, une des manières par lesquelles nous commençons à faire le travail de réclamation de nos êtres entiers – nos êtres entiers libérés et libres – est de réclamer notre accès au plaisir.

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha a écrit dans sa contribution à Pleasure Activism,

Je sais que, pour la plupart des gens, les mots « soins » et « plaisir » ne peuvent absolument pas faire partie d’une même phrase. Nous nageons toutes dans la haine validiste de nos corps qui ont des besoins, et on nous propose un choix vraiment merdique : n’avoir aucun besoin et obtenir l’autonomie, la dignité et le contrôle de notre vie ou admettre que nous avons besoin de soins et perdre tout cela.

Le pouvoir que cela a? Nous comprenons nos traumatismes, donc nous comprenons ceux des autres; nous incarnons les sensations que nous vivons et y prêtons attention plutôt que de les négliger ou les éviter. Les manières dont nous accédons au plaisir nous donnent envie de partager cette joie dans nos communautés. En tenant compte des traumatismes, on se donne davantage de place pour faire l’expérience de tout cela et on se donne à nous-mêmes, et aux autres, la permission de guérir. Imaginez une communauté dans laquelle tout le monde a accès à des ressources et a le temps de vivre une vie plaisante, de la manière dont toutes et tous le veulent et le méritent. Dans laquelle les traumatismes spatiaux sont atténués parce que les personnes qui occupent ces espaces ont conscience des traumatismes, sont pleines d’attention bienveillante. N’est-ce pas ça, la guérison? N’est-ce pas un travail au niveau des traumatismes générationnels? N’est-ce pas la base pour un avenir plus sain et durable pour tout le monde?

Il est temps de nous reconnecter à cette sagesse ancestrale selon laquelle nous méritons de vivre des vies pleines. Nous devons reprendre contact avec notre droit naturel à la joie et à l’existence pour nous-mêmes. De ressentir du plaisir pour le simple plaisir. De ne pas vivre des vies de terreur. Cela paraît radical ; cela semble radical. Dans un monde où nous avons été socialisées et traumatisées à taire, à avoir peur, à ressentir et à rester impuissantes, à être cupides et à vivre avec ces problèmes structurels qui entraînent des maladies mentales, quel cadeau et quel émerveillement que de commencer à ressentir, d’être dans une communauté avec celles qui ressentent, dans laquelle nous sommes sainement interdépendantes, de s’aimer mutuellement et complètement. La sensation est radicale. Le plaisir est radical. La guérison est radicale.

Vous avez la permission de ressentir du plaisir. Vous avez la permission de danser, créer, faire l’amour à vous-même et à d’autres, célébrer et cultiver la joie. Vous êtes encouragées à le faire. Vous avez la permission de guérir. Ne le retenez pas à l’intérieur, n’essayez pas de traverser cela toute seule. Vous avez la permission de faire le deuil. Et vous avez la permission de vivre.

- Adrienne Marre Brown « You Have Permission »

L’incarnation somatique nous permet d’explorer notre traumatisme, d’y travailler et de faire des connexions significatives avec nous-mêmes et avec le collectif. Faire cela sur la durée entretient notre guérison. Tout comme le traumatisme, la guérison n’est pas un événement à occurrence unique. Cette guérison nous aide à aller vers la libération individuelle et collective.

Dans « A Queer Politics of Pleasure », Andy Johnson parle de la manière dont le fait de rendre le plaisir queer nous apporte des sources de guérison, d’acceptation, de relâchement, de jeu, d’entièreté, de défiance, de subversion et de liberté. Quelle ouverture! En incarnant le plaisir de manière si holistique, si queer, nous sommes en mesure de reconnaître la limite.

Rendre le plaisir queer nous pose également les questions à l’intersection de nos rêves et de nos réalités vécues.

Qui est assez libre ou considéré assez méritant pour ressentir du plaisir? Quand sommes-nous autorisés à ressentir le plaisir ou à être satisfaits? Avec qui pouvons-nous faire l’expérience du plaisir? Quel type de plaisir est accessible? Qu’est-ce qui nous limite dans notre accès total à notre potentiel érotique et de satisfaction?

- Andy Johnson, « A Queer Politics of Pleasure »

Lorsque nos pratiques de plaisir, qui prennent en compte le traumatisme, sont ancrées dans les soins communautaires, nous commençons à répondre à quelques-unes de ces questions. Nous commençons à en comprendre le potentiel libérateur. En tant qu’activistes du plaisir, c’est la réalité au sein de laquelle nous nous ancrons. La réalité qui dit : « mon plaisir peut-être fractal, mais il a le potentiel de guérir non seulement moi et ma communauté, mais des lignées futures ».

Je suis un système entier; nous sommes des systèmes entiers. Nous ne sommes pas que nos douleurs, que nos peurs, et que nos pensées. Nous sommes des systèmes entiers prévus pour le plaisir et nous pouvons apprendre comment dire oui depuis l’intérieur.

- Prentis Hemphill, entretien mené par Shar Jossell

Il y a un monde de plaisir qui nous permet de commencer à nous comprendre de manière holistique, avec des façons qui nous donnent la place de reconstruire les réalités qui affirment que nous sommes capables et que nous méritons du plaisir quotidien. Le BDSM, un de mes plaisirs les plus profonds, me permet d’entrevoir ces réalités où je peux sentir et guérir mon traumatisme, tout en sentant les incommensurables possibilités de dire oui depuis l’intérieur. Alors que le traumatisme me bloque dans un cycle de combat ou de fuite, le bondage, l’agenouillement, l’impact et les jeux de respiration m’encouragent à rester ancrée et connectée, me reconnectant à ma restauration. Le plaisir ludique me permet de guérir, d’identifier où l’énergie traumatique est emmagasinée dans mon corps et d’y centrer mon énergie. Il me permet d’exprimer les sensations que ressent mon corps avec des cris de douleur et de satisfaction, d’exprimer mon « non » sans aucune peur et de me délecter dans le « oui, carrément ». Avec un plan de sécurité, des soins après la pratique et une compréhension approfondie du traumatisme, la perversion offre un lieu de plaisir et de guérison d’une valeur inestimable.

Donc, que votre plaisir prenne la forme de la préparation d’un repas à votre rythme, d’avoir des relations sexuelles, de rester au lit plusieurs jours avec vos partenaires, de participer à des collectifs de soins adaptés aux situations de handicap, d’avoir quelqu’un qui vous crache dans la bouche, de faire des sorties accessibles, d’avoir des rendez-vous de câlins, de participer à une soirée dansante en ligne, de passer du temps dans votre jardin, d’être étouffée dans un donjon,

J’espère que vous prenez le plaisir avec vous partout où vous allez. J’espère qu’il vous guérit, vous et celleux qui vous entourent.

Reconnaître le pouvoir de l’érotique au sein de nos vies peut nous donner l’énergie de poursuivre le véritable changement au sein de notre monde.

- Audre Lorde, « Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power »

Cette édition du journal, en partenariat avec Kohl : a Journal for Body and Gender Research (Kohl : une revue pour la recherche sur le corps et le genre) explorera les solutions, propositions et réalités féministes afin de transformer notre monde actuel, nos corps et nos sexualités.

نصدر النسخة هذه من المجلة بالشراكة مع «كحل: مجلة لأبحاث الجسد والجندر»، وسنستكشف عبرها الحلول والاقتراحات وأنواع الواقع النسوية لتغيير عالمنا الحالي وكذلك أجسادنا وجنسانياتنا.

Caroline ha estado de forma periódica en AWID; en fechas anteriores, organizó los foros de 2005 y 2008 en Bangkok y Ciudad del Cabo, y cumplió otras funciones institucionales. Antes de incorporarse a AWID, impartió clases de inglés de pregrado, luego abandonó el ámbito académico para dirigir el Festival Internacional de Cine Asiático de Toronto y trabajar en otros proyectos. En fechas más recientes, se ha desempeñado como Responsable de Operaciones en Spring Strategies. Fuera del plano laboral, Caroline generalmente puede ser hallada a su jardín, en comunión con sus queridas plantas e intentando hacer las paces con los insectos y los roedores que suelen aparecer.

Notre tout premier programme du Club de cinéma féministe est désormais accessible : « La tendresse est la plus tranchante des résistances » fait référence à une série de films sur les réalités féministes d’Asie et du Pacifique, sélectionnés par Jess X Snow.

Don't know where to start? Let's try understanding the filters.