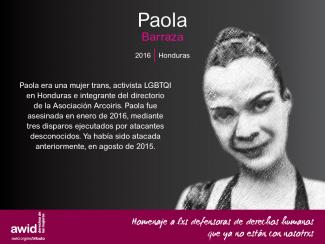

Paola Barraza

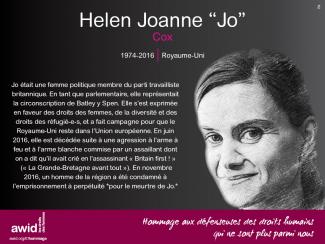

WHRDs are self-identified women and lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LBTQI) people and others who defend rights and are subject to gender-specific risks and threats due to their human rights work and/or as a direct consequence of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

WHRDs are subject to systematic violence and discrimination due to their identities and unyielding struggles for rights, equality and justice.

The WHRD Program collaborates with international and regional partners as well as the AWID membership to raise awareness about these risks and threats, advocate for feminist and holistic measures of protection and safety, and actively promote a culture of self-care and collective well being in our movements.

WHRDs are exposed to the same types of risks that all other defenders who defend human rights, communities, and the environment face. However, they are also exposed to gender-based violence and gender-specific risks because they challenge existing gender norms within their communities and societies.

We work collaboratively with international and regional networks and our membership

We aim to contribute to a safer world for WHRDs, their families and communities. We believe that action for rights and justice should not put WHRDs at risk; it should be appreciated and celebrated.

Promoting collaboration and coordination among human rights and women’s rights organizations at the international level to strengthen responses concerning safety and wellbeing of WHRDs.

Supporting regional networks of WHRDs and their organizations, such as the Mesoamerican Initiative for WHRDs and the WHRD Middle East and North Africa Coalition, in promoting and strengthening collective action for protection - emphasizing the establishment of solidarity and protection networks, the promotion of self-care, and advocacy and mobilization for the safety of WHRDs;

Increasing the visibility and recognition of WHRDs and their struggles, as well as the risks that they encounter by documenting the attacks that they face, and researching, producing, and disseminating information on their struggles, strategies, and challenges:

Mobilizing urgent responses of international solidarity for WHRDs at risk through our international and regional networks, and our active membership.

A los seis años, me enteré de que mi abuelo tenía una sala de cine. Mi madre me contó que la había abierto a principios de la década de 1960, cuando ella también tenía unos seis años. Recordaba que la primera noche proyectaron La novicia rebelde / Sonrisas y lágrimas...

Como organizadorx, puedes proponer hasta dos (2) actividades, y también puedes asociarte en otras propuestas.

Ester Lopes is a dancer and writer whose research focuses on the body, gender, race, and class relations. She is a Pilates instructor and art educator. Ester graduated in Contemporary Theater – Creative Processes (at FAINC) and in Dance and Body Consciousness (at USCS). Her musical specialization includes popular singing and percussion. She received training in Novos Brincantes with Flaira Ferro, Mateus Prado, and Antonio Meira at Brincante Institute in 2015 and 2016.

الخامسة مساءً، اليوم

خطّ كتابة الدعوة –

متحفّظ وجاف –

رأيته خمس مرّات في خمس سنوات.

جسدي مُستنفَر،

محموم.

أحتاج لمضاجعة نفسي أوّلًا.

المدُّ عالٍ الليلة

وأنا

أنتشي.

أريدُ إبطاءَ كلَّ شيء،

واستطعام الوقت والفراغ،

أن أحفرهما

في الذاكرة.

*

لم آتِ أبدًا إلى هذا الجزء من البلدة.

الأماكن المجهولة تثيرني،

[كذلك] الطريقة التي تقاوم بها الأشلاء والعروق والعظام

الاضمحلال،

مصيرهم غامض.

عند الباب أعيدُ التفكير.

الرواق قاتم السواد

يجعلني أتوقّف.

على الناحية الأخرى،

مثل اللعنة، يُفتَح باب

من الروائح والألوان

على عَصْرٍ مُشمس.

النسيم

يجعل شعري يرقص،

يثير فضوله،

يدفعه للحركة.

أسمعُ أزيزَ الكرسي المتحرّك،

يشكّل الظلال.

عندها أراهم:

وجه فهد

وجسدٌ مثل جسدي

وأجِدني راغبة بكليهما

مرّة أخرى.

يقترب المخلوق منّي.

إيماءاتهم تكتب جملة؛

كلّما اقتربت منهم،

أتبيّن تفاصيلها:

ذبول، لحم، غِبطة

بأمر ٍمنهم، تزحف الكرمة

التي تغطّي الرُواق

مُعانقةً الصخور الدافئة

وتتسلّق الحائط كالأفعى.

لقد أصبح فعلًا،

«أن تقفز»،

أُعيدَ توجيهي عندما أشارت مخالبهم

نحو سرير الكرم في المنتصف.

أسمع العجلات خلفي،

ثم أسمع ذلك الصوت.

يُدوي

بشكلٍ لا مثيل له.

أجنحتهم الطويلة السوداء

ترتفع نحو السقف

ثم تندفع للأمام.

عينا الهرّة تفحص كلّ تفصيلة،

كلّ تغيّر،

كلّ تَوق.

هل يمكن أن تُذيب الرغبة عضلاتك؟

هل يمكن أن تكون أحلى من أقوى المهدّئات؟

فهدٌ يخيط العالم،

عبرَ اختلافاتنا،

غازلًا الدانتيل حول ركبتيَّ.

هل يمكن للرغبة أن تسحق تباعُد العالم،

أن تكثّف الثواني؟

مازالوا يقتربون،

تلتقي عين الفهد بعين الإنسان،

تتنشّق الهواء،

تُحوِّل الجسد إلى

إلحاح.

يخفقون بأجنحتهم للأسفل.

هائجة،

تلتفّ الكرمة حول خصري/ خسارتي.

لسانهم يرقّق الوقت،

تتبدّل الآراء،

يُسكِّن، بسحرهم،

ما يشتعل أسفل [السطح].

أرى العالم فيك، والعالم مُنهَك.

ثم يتوسّلون:

دعيني أقتات عليك.

Related content

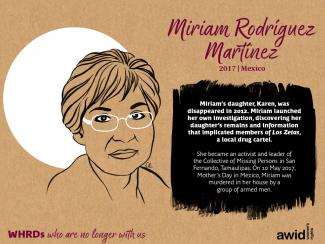

The Guardian: Mexican woman who uncovered cartel murder of daughter shot dead

The Economist: Obituary: Miriam Rodríguez Martínez died on May 10th

New York Times: Gunmen Kill Mexican Activist for Parents of Missing Children

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner: Mexico: UN rights experts strongly condemn killing of human rights defender and call for effective measures to tackle impunity

Le traumatisme, ce n’est pas l’événement, c’est la manière dont nos corps répondent aux événements qui nous semblent dangereux. Et le trauma reste souvent coincé dans notre corps, jusqu’à ce que nous l’abordions. Il n’est pas possible de faire autrement – c’est ainsi que notre corps l’entend.

«Si podemos heredar un trauma, ¿podemos heredar una huella relacionada con el amor?»

Mientras el capitalismo heteropatriarcal continúa forzándonos al consumismo y el acatamiento, observamos que nuestras luchas están siendo compartimentadas y separadas por fronteras tanto físicas como virtuales.

Si tu actividad es seleccionada, el equipo de AWID te contactará para evaluar y responder a tus necesidades de interpretación y accesibilidad.

Moriviví is a collective of young female artists, working on public art since April 2013. Based in Puerto Rico, we’ve gained recognition for the creation of murals and community led arts.