Resourcing Feminist Movements

The “Where is the Money?” #WITM survey is now live! Dive in and share your experience with funding your organizing with feminists around the world.

Learn more and take the survey

Around the world, feminist, women’s rights, and allied movements are confronting power and reimagining a politics of liberation. The contributions that fuel this work come in many forms, from financial and political resources to daily acts of resistance and survival.

AWID’s Resourcing Feminist Movements (RFM) Initiative shines a light on the current funding ecosystem, which range from self-generated models of resourcing to more formal funding streams.

Through our research and analysis, we examine how funding practices can better serve our movements. We critically explore the contradictions in “funding” social transformation, especially in the face of increasing political repression, anti-rights agendas, and rising corporate power. Above all, we build collective strategies that support thriving, robust, and resilient movements.

Our Actions

Recognizing the richness of our movements and responding to the current moment, we:

-

Create and amplify alternatives: We amplify funding practices that center activists’ own priorities and engage a diverse range of funders and activists in crafting new, dynamic models for resourcing feminist movements, particularly in the context of closing civil society space.

-

Build knowledge: We explore, exchange, and strengthen knowledge about how movements are attracting, organizing, and using the resources they need to accomplish meaningful change.

-

Advocate: We work in partnerships, such as the Count Me In! Consortium, to influence funding agendas and open space for feminist movements to be in direct dialogue to shift power and money.

Related Content

Snippet - WITM Why now_col 1 - RU

Почему сейчас?

Феминистские движения, движения за права женщин, гендерную справедливость, ЛГБТКИ+ и смежные движения по всему миру переживают критический момент, сталкиваясь с мощной негативной реакцией на ранее завоеванные права и свободы. Последние годы привели к быстрому росту авторитаризма, жестоким репрессиям в отношении гражданского общества и криминализации правозащитниц(-ков) с разнообразной гендерной самоидентификацией, эскалации войн и конфликтов во многих частях света, продолжающейся экономической несправедливости, – и все это на фоне кризиса в области здравоохранения, экологии и климата.

Embodying Trauma-Informed Pleasure | Small Snippet EN

Embodying Trauma-Informed Pleasure

Trauma is not the event; it is how our bodies respond to events that feel dangerous to us. It is often left stuck in the body, until we address it. There’s no talking our body out of this response – it just is.

Snippet - WITM Our objectives - AR

أهداف استطلاع "أين المال"

|

تقديم تحليل محدّث، قوي، مبني على الأدلة ومسيّر نحو النشاط عن وقائع التمويل النسوي للتنظيمات النسوية ووضع البيئة التمويلية النسوية لأعضاء وعضوات AWID، الشركاء/ الشريكات في الحركة والممولين/ات. |

1 |

|

|

تحديد وإظهار الفرص للتحول لتمويل أفضل وأكبر للحركات النسوية، لكشف الحلول الزائفة ووقف التوجه الذي يجعل التمويل يتحرك ضد الأجندات التقاطعية أو أجندات العدالة الجندرية. |

2 |

|

|

تحديد الرؤى المقترحات والأجندات النسوية، لتمويل يحقق العدالة. |

3 |

|

Snippet Kohl - Plenary: The revolution will be feminist | AR

جلسة عامة | ستكون الثورة نسوية وإلّا لن تكون ثورة

مع منال التميمي وبوبولينا مورينو وكارولينا فيكيفيتش وأنووليكا نوجوزي أوكونجو

Кому следует принять участие в опросе?

Группы, организации и движения, работающие исключительно или главным образом в интересах женщин, девочек, гендерной справедливости, прав ЛГБТКИ+ людей во всех регионах и на всех уровнях, как недавно созданные, так и давно существующие.

O nosso grupo, organização e/ou movimento não recebeu ou mobilizou financiamento de financiadores externos. Devemos participar no inquérito?

Sim! Reconhecemos e valorizamos diferentes motivos pelos quais as feministas nos seus respetivos contextos não dispõem de financiamento externo: desde não serem elegíveis para se candidatar a subsídios e/ou receber dinheiro do exterior, até dependerem de recursos gerados autonomamente como uma estratégia política por si só. Queremos saber mais sobre vocês, independentemente da vossa experiência com financiamento externo.

Beijing Unfettered: the Power of Young Feminist Movements

In partnership with young feminist activists and youth-led organizations, AWID co-organized Beijing Unfettered in parallel to and independently from Beijing+25.

ما هي لغات استطلاع "أين المال" الرسمية؟

حالياً سيتواجد الاستطلاع على منصة KOBO باللغات العربية، الإنجليزية، الفرنسية، البرتغالية، الروسية والاسبانية. ستكون لديكم/ن الفرصة لاختيار اللغة التي تريدون تعبئة الاستطلاع بها في بداية الاستطلاع.

Snippet "un"Inclusive Feminism_Fest (EN)

"un"Inclusive Feminism:

The voiceless girls in the Haitian feminist movement

Naike Ledan

Semi Kaefra Alisha Fermond, Trans Rights Activist ACIFVH

Natalie Desrosiers

Fédorah Pierre-Louis

Наша группа не имела ежегодного финансирования в период с 2021 по 2023 год. Можем ли мы пройти опрос?

Да, мы хотим получить ваш ответ, независимо от того, сколько раз (один, два или три) вы получали финансирование в период между 2021 и 2023 годами.

Porque é que são necessários o nome e as informações de contacto do grupo/organização e/ou movimento que preencher o inquérito?

Pedimos estes dados para facilitar a revisão das respostas, para evitar respostas duplicadas e para poder entrar em contacto com o seu grupo caso não tenha conseguido completar o inquérito e/ou tenha dúvidas ou perguntas adicionais. Para mais informações sobre como utilizamos as informações pessoais que recolhemos através do nosso trabalho, clique aqui.

إلى متى يمكن الإجابة على الاستطلاع؟

وسيكون التحقيق مفتوحًا حتى 31 أغسطس 2024. الرجاء تكملته خلال هذا الوقت للتأكد بأن تشمل ردودكم/ن في التحليل.

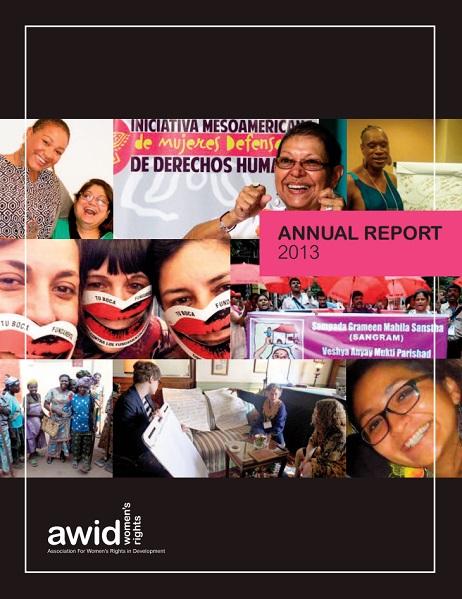

Annual Report 2013

2013 marked the beginning of our 2013-2016 Strategic Plan, developed in response to the current global context. This report provides highlights of our analysis of the global context, how we position ourselves as a global feminist membership organization in this context, the outcomes we seek to achieve, and how our work is organized to achieve these outcomes.

Membership why page - Loyiso Lindani

I believe empowered women empower women and that is why I’ve had an incredible time being an AWID member. My knowledge and understanding of Feminism and intersectionality has been broadened by the exposure I received being part of the AWID Community Street Team. I hope more women join and share topics and ideas that will help other women.

- Loyiso Lindani, South Africa.

Stephanie Bracken

Stephanie Bracken is a feminist who is dedicated to building and supporting strong systems that meet the needs of the moment and the people who interact with them, and serve principles of justice. She holds a Master of Human Rights from the University of Sydney and a BA in Gender Studies, History, and Philosophy from McGill University, and has experience working with feminist and social justice organizations on monitoring, evaluation & learning, strategic work planning, governance, project management, and building operational systems and processes. Stephanie is based in Tiohtià:ke/Montreal, where she enjoys singing with others, camping, fiber arts, and spending time with her kids and community.

Snippet - Resources to rally - EN

Resources to rally through CSW69 with

Juhi

Juhi is a tech enthusiast with a Bachelor's degree in Computer Engineering from Gujarat Technological University and a postgraduate background in Wireless Telecommunications and Project Management from Humber College. With a passion for problem-solving and a love for staying ahead in the ever-evolving tech landscape, Juhi has found herself navigating through various industries as an IT Technician. to the nurturing environment of the School Board, Juhi has had the opportunity to apply her technical skills in diverse settings, always embracing new challenges with enthusiasm. Beyond the code and circuits, Juhi loves life's adventures. Exploring new places and cultures is like a breath of fresh air to her. Whether it's discovering hidden gems in the city, trying out exotic cuisines, or embarking on thrilling adventure sports, Juhi is always up for new experiences.

Snippet - WCFM Airtable iFrame - EN

Explore the Database now!

Don't know where to start? Let's try understanding the filters.

Fatima Qureshi

A nomad of cultures, born in Hong Kong, rooted in Turkish-Pakistani heritage, Fatima’s love for narratives - both in reading and co-creating them - fueled her passion for communications activism. Supported by her education in journalism, Fatima has worked for 7 years in digital and media communications fields with NGOs that provide education opportunities and legal aid to refugee and asylum seekers, as well as with the Muslim feminist movement which applies feminist and rights-based lenses in understanding and searching for equality and justice within Muslim legal tradition. She is a regular op-ed writer on feminist issues in the Global South.

Through storytelling in this hyper-digital age of social media, Fatima continues to collaborate with community organizers and grassroots activists to create audiovisual content with the aim to cultivate bridges of understanding towards collective liberation and decolonization. On days when she’s not working, she intently watches independent feminist films coming from Iran, Morocco and Pakistan and on other days, she performs spoken word poetry with her comrades in Kuala Lumpur.