Mai Ghoussoub

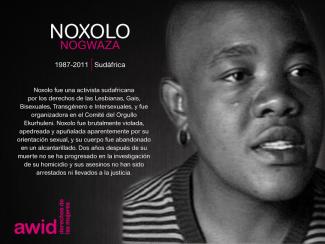

Lxs defensorxs se identifican a sí mismas como mujeres y personas lesbianas, bisexuales, transgénero, queer e intersex (LBTQI) y otrxs que defienden derechos y que debido a su trabajo en derechos humanos están bajo riesgos y amenazas específicos por su género y/o como consecuencia directa de su identidad de género u orientación sexual.

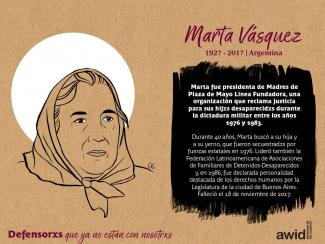

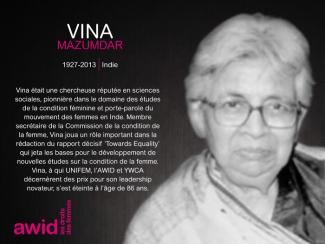

Lxs defensorxs son objeto de violencia y discriminación sistemáticas debido a sus identidades y su inclaudicable lucha por derechos, igualdad y justicia.

El Programa Defensorxs colabora con contrapartes internacionales y regionales así como con lxs afiliadxs de AWID para crear conciencia acerca de estos riesgos y amenazas, abogar por medidas de protección y de seguridad que sean feministas e integrales, y promover activamente una cultura del autocuidado y el bienestar colectivo en nuestros movimientos.

lxs defensorxs enfrentan los mismos tipos de riesgos que todxs lxs demás defensorxs de derechos humanos, de comunidades y del medio ambiente. Sin embargo, también están expuestas a violencia y a riesgos específicos por su género porque desafían las normas de género de sus comunidades y sociedades.

Nos proponemos contribuir a un mundo más seguro para lxs defensorxs, sus familias y comunidades. Creemos que actuar por los derechos y la justicia no debe poner en riesgo a lxs defensorxs, sino que debe ser valorado y celebrado.

Promoviendo la colaboración y coordinación entre organizaciones de derechos humanos y organizaciones de derechos de las mujeres en el plano internacional para fortalecer la capacidad de respuesta en relación a la seguridad y el bienestar de lxs defensorxs.

Apoyando a las redes regionales de defensorxs y de sus organizaciones, tales como la Iniciativa Mesoamericana de Mujeres Defensorxs de Derechos Humanos y la WHRD Middle East and North Africa Coalition [Coalición de Defensorxs de Derechos Humanos de Medio Oriente y África del Norte], promoviendo y fortaleciendo la acción colectiva para la protección, poniendo el énfasis en establecer redes de solidaridad y protección, promover el autocuidado y la incidencia y movilización por la seguridad de lxs defensorxs.

Aumentando la visibilidad y el reconocimiento de lxs defensorxs y sus luchas, así como de los riesgos que enfrentan, a través de la documentación de los ataques que sufren, e investigando, produciendo y difundiendo información sobre sus luchas, estrategias y desafíos.

Movilizando respuestas urgentes de solidaridad internacional para lxs defensorxs que están en riesgo a través de nuestras redes internacionales y regionales y de nuestrxs afiliadxs activxs.

Pour revendiquer votre pouvoir en tant qu’experte sur la situation du financement des mouvements féministes.

Une communauté en ligne pour et par les jeunes féministes qui militent pour les droits humains des femmes, l'égalité de genre et la justice sociale dans le monde entier

Finance des projets initiés par de jeunes féministes. Vise à renforcer la capacité des organisations de jeunes féministes à mobiliser des ressources pour leurs actions et à encourager des bailleur-euse-s de fonds et d’autres allié-e-s à financer l’activisme des jeunes féministes.

Cette plateforme sera l’espace de référence pour accéder à des informations et à des ressources concernant la sauvegarde de l'universalité des droits humains dans les espaces internationaux et régionaux.

Visitez le site (en anglais)

Un site pour en savoir plus sur les mesures d’urgence entreprises pour protéger les défenseuses des droits humains et pour trouver des outils et des ressources au soutien de leur travail et de leur bien-être.

Une initiative régionale créée pour prévenir, répondre, documenter et rendre publics tous les cas de violence contre les défenseuses des droits humains dans la région mésoaméricaine.

Visitez le site (en anglais et en espagnol)

Un réseau qui réalise un travail de plaidoyer et propose des ressources pour protéger et soutenir les défenseuses des droits humains dans le monde entier.

Visitez le site (en anglais)

Une coalition d’organisations féministes, de droits des femmes, de développement, de justice sociale et d’organisations de terrain qui conteste le programme mondial de développement et plaide pour qu’il soit recadré.

Visitez le site (en anglais)

Le rôle du groupe consiste à assurer la pleine participation des groupes de femmes non gouvernementaux aux processus politiques de l'ONU sur le développement durable, le programme de l’après-2015 et les questions environnementales.

Visitez le site (en anglais)

Une alliance d’organisations et de réseaux de femmes qui font un travail de plaidoyer en faveur de l'égalité de genre, de l'autonomisation des femmes et des droits humains dans le cadre des processus des Nations unies relatifs à la composante Financement du développement (FdD).

Visitez le site (en anglais)

El proceso de la Financiación para el Desarrollo (FpD) de Naciones Unidas (ONU) se propone abordar distintas formas de financiación y cooperación para el desarrollo. Según lo acordado en el Consenso de Monterrey, se centra en seis áreas prioritarias:

Vous pouvez suivre le travail de ces collectifs sur les réseaux sociaux et sites internet suivant:

La dotación de recursos de los movimientos feministas es fundamental para garantizar una presencia más justa y pacífica y un futuro en libertad. En las últimas décadas, los donantes comprometieron una cantidad más considerable de dinero para la igualdad de género; sin embargo, apenas el 1% del financiamiento filantrópico y para el desarrollo se ha destinado real y directamente a dotar de recursos al cambio social encabezado por los feminismos.

La dotación de recursos de los movimientos feministas es fundamental para garantizar una presencia más justa y pacífica y un futuro en libertad. En las últimas décadas, los donantes comprometieron una cantidad más considerable de dinero para la igualdad de género; sin embargo, apenas el 1% del financiamiento filantrópico y para el desarrollo se ha destinado real y directamente a dotar de recursos al cambio social encabezado por los feminismos.

Para luchar por la abundancia y acabar con esta escasez crónica, la encuesta ¿Dónde está el dinero? es una invitación a lxs promotorxs feministas y por la justicia de género a sumarse al proceso de la construcción colectiva de razones fundadas y evidencias para movilizar más y mejores fondos y recobrar el poder en el ecosistema de financiamiento de hoy. En solidaridad con los movimientos que continúan invisibilizados, marginados y sin acceso a financiamiento básico, a largo plazo, flexible y fiduciario, la encuesta ¿Dónde está el dinero? pone de relieve el estado real de la dotación de recursos, impugna las falsas soluciones y señala cómo los modelos de financiamiento necesitan modificarse para que los movimientos prosperen y puedan hacer frente a los complejos desafíos de nuestro tiempo.

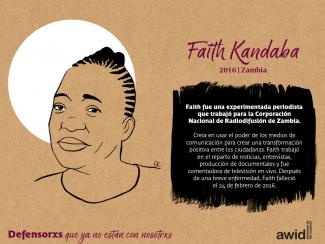

Estas 20 Defensoras de derechos humanos (WHRDs, por las siglas en inglés) trabajaron como periodistas, y de manera más amplia, en los medios comunicación de México, Colombia, Fiji, Libia, Nepal, Estados Unidos de Norteamérica, Nicaragua, Filipinas, Rusia, Alemania, Francia, Afganistán, y el Reino Unido. De ellas, 16 han sido asesinadas, y la causa de muerte en uno de los casos sigue sin ser esclarecida. Por esto, en este Día Mundial de la Libertad de Prensa, por favor únete a nosotrxs para conmemorar la vida y el trabajo de estas mujeres, compartiendo las memes aquí incluidas con tus colegas, amistades y redes, utilizando los hashtags #LibertadDePrensa y #WHRDs.

Los aportes del trabajo realizado por estas mujeres fueron celebrados y honrados en nuestro Tributo virtual para defensoras que ya no están con nosotrxs.

Por favor, haz click en cada imagen de abajo para ver una versión más grande y para descargar como un archivo.

La convocatoria para la propuesta de sesión ahora está cerrada.

Lanzamos el Llamado a Proponer Actividades el 19 de noviembre de 2019 y la última fecha para recibir propuestas fue el 14 de febrero de 2020.

Identify and demonstrate opportunities to shift more and better funding for feminist organizing, expose false solutions and disrupt trends that make funding miss and/or move against gender justice and intersectional feminist agendas.

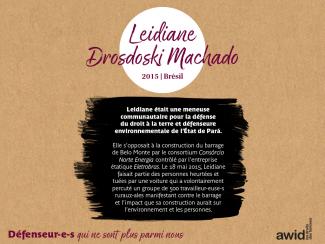

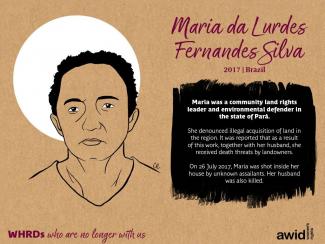

Les données que nous avons recueillies pour élaborer notre hommage montrent à quel point le Mexique est un pays dangereux pour les défenseuses. Sur les 12 femmes mexicaines défenseuses des droits humains que nous commémorons cette année, 11 ont été assassinées. Elles étaient des journalistes ou des activistes, des défenseuses des droits des femmes ou de ceux des personnes trans*. Nous vous invitons à vous joindre à nous pour rendre hommage à ces défenseuses, à leur travail et à l’héritage qu’elles nous ont laissé. Faites circuler ces mèmes auprès de vos collègues et amis ainsi que dans vos réseaux et twittez en utilisant les hashtags #WHRDTribute et #16Jours.

S'il vous plaît cliquez sur chaque image ci-dessous pour voir une version plus grande et pour télécharger comme un fichier

Pronto brindaremos esta información. ¡Mantente sintonizadx!

NOUS SOMMES LA SOLUTION

We are the Solution